How to cite this article: Robert L. Lindsey, “Introduction to A Hebrew Translation of the Gospel of Mark,” Jerusalem Perspective (2014) [https://www.jerusalemperspective.com/16547/].

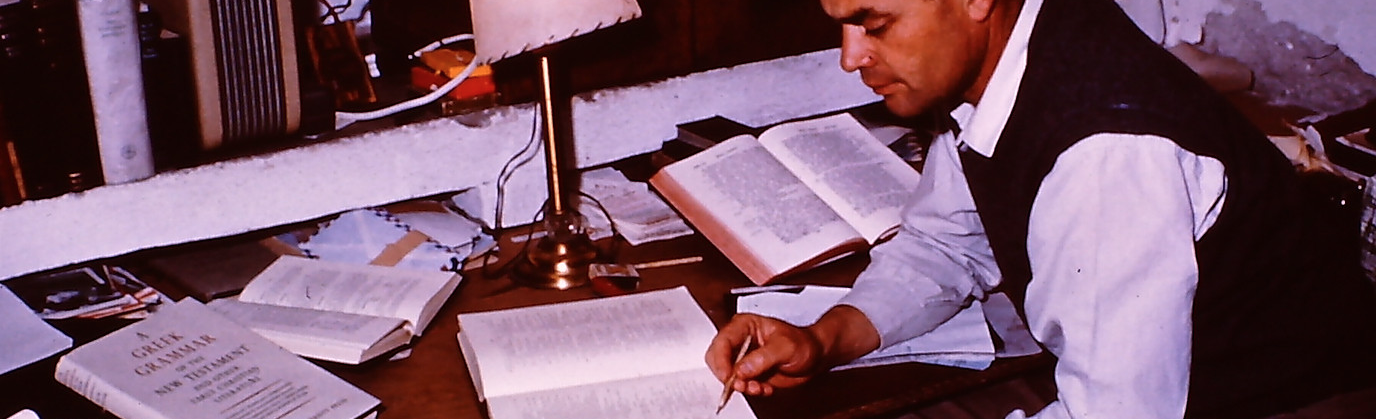

My Hebrew translation of the Gospel of Mark[1] grew out of an eight-year personal encounter with this Gospel. Not long after Israel’s independence, I came to the conclusion that a new Hebrew translation of the New Testament was badly needed, especially by the Hebrew-speaking Christian congregations of the State of Israel. I chose to begin with the Gospel of Mark, under the impression that it was the earliest of the canonical Gospels and because it contained the kind of simple Greek text that would make translation relatively easy. According to the widely-held theory of Markan Priority, which I had no reason at that time to doubt, Matthew and Luke used this Gospel as one of their principal sources. According to this theory, Matthew and Luke wrote independently of each other and used not only the Gospel of Mark, but also a second common source usually called “Q.” It is also generally held that the author of Mark derived much of his information from Aramaic oral sources.

| Table of Contents |

1. Introduction 4. The Significance of the Minor Agreements 9. The Hypotheses of Augustine and Griesbach 11. Confirming the Priority of Luke 12. Mark’s Midrashic Technique 13. The Confirmation of Lockton’s Work 14. Collaboration with Professor Flusser 15. Sources of the Markan Pick-ups |

To my surprise, however, examination of the Greek text of Mark revealed that its Greek word order and idiom were more like Hebrew than Greek. This gave me the frightening feeling that my translation was “restoring” an original Hebrew text rather than creating a new one. This experience caused me to wonder whether Mark might be a literal translation of a Hebrew original.

At about this time I was introduced by M. K. Moulton of the British and Foreign Bible Society to Professor George D. Kilpatrick of Queens College, Oxford. Professor Kilpatrick, whose research on the Gospel of Matthew is well known,[2] was kind enough to invite me to Oxford for a few days as his guest and spent many hours listening with a critical but patient ear to my theories and questions. Professor Kilpatrick introduced me to a series of valuable linguistic studies on the Gospel of Mark written by his predecessor at Queens College, C. H. Turner, and printed in volumes xxv-xxviii of the Journal of Theological Studies.[3] From Turner’s articles I learned that Mark’s Gospel includes a number of parenthetical notes that are best explained by supposing that Mark used written Greek stories but decided to annotate them in an attempt to make them clearer to his readers. In the months that followed I had occasion to investigate the style of these “parenthetic sections,” as Turner called them. I discovered that in at least one of these annotations, Mark 7:3-4, the word order was far less Hebraic than the usual Markan word order.

Premium Members and Friends of JP must be signed in to view this content.

If you are not a Premium Member or Friend, please consider registering. Prices start at $5/month if paid annually, with other options for monthly and quarterly and more: Sign Up For Premium

Notes

- Robert L. Lindsey, A Hebrew Translation of the Gospel of Mark (2d ed.; Jerusalem: Dugith, 1973). ↩

- Notable among G. D. Kilpatrick’s works are, The Origins of the Gospel according to St Matthew (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1946); and The Trial of Jesus (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1953). ↩

- C. H. Turner, “Marcan Usage: Notes, Critical and Exegetical, on the Second Gospel,” JTS 25 (100) (1924): 377-386; idem, “Marcan Usage: Notes, Critical and Exegetical, on the Second Gospel,” JTS 25 (101) (1924): 12-20; idem, “Marcan Usage: Notes, Critical and Exegetical, on the Second Gospel,” JTS 26 (102) (1925): 145-156; idem, “Marcan Usage: Notes, Critical and Exegetical, on the Second Gospel,” JTS 26 (103) (1925): 225-240; idem, “Marcan Usage: Notes, Critical and Exegetical, on the Second Gospel,” JTS 26 (104) (1925): 337-346; idem, “Marcan Usage: Notes, Critical and Exegetical, on the Second Gospel,” JTS 26 (105) (1925): 58-62; idem, “Marcan Usage: Notes, Critical and Exegetical, on the Second Gospel,” JTS 28 (1926): 9-30; idem, “A Textual Commentary on Mark I,” JTS 28 (1927): 145-158; idem, “Marcan Usage: Notes, Critical and Exegetical, on the Second Gospel,” JTS 28 (1927): 349-362; idem, “Western Readings in the Second Half of St Mark’s Gospel,” JTS 29 (113) (1927): 1-16; idem, “Did Codex Vercellenis Contain the Last Twelve Verses of St Mark?” JTS 29 (113) (1927): 16-18; idem, “Marcan Usage: Notes, Critical and Exegetical, on the Second Gospel,” JTS 29 (115) (1928): 275-289; idem, “Marcan Usage: Notes, Critical and Exegetical, on the Second Gospel,” JTS 29 (116) (1928): 346-361. ↩

![Robert L. Lindsey [1917-1995]](https://www.jerusalemperspective.com/wp-content/uploads/userphoto/28.jpg)