Sometimes the work we do for The Life of Yeshua: A Suggested Reconstruction can seem a little hard on the Gospel of Mark. Our study of the Synoptic Gospels suggests that the author of Mark extensively rewrote the stories he incorporated into his Gospel. We believe that the parallel versions in the Gospels of Luke and Matthew are usually closer to the wording of the stories as they appeared in the Greek Translation of the Hebrew Life of Yeshua than what we find in Mark. Sometimes our research might leave readers wondering whether we have anything positive to say about Mark.

In this blog I want to focus on a few deeply positive aspects regarding Mark’s Gospel that emerge from our Life of Yeshua research. The first is that if Robert Lindsey is correct that the author of Mark relied on the Gospel of Luke as the primary source for his rewritten Gospel, then this is a very strong endorsement of Luke’s Gospel. The author of Mark must have held the Gospel of Luke in high regard to have chosen Luke as the basis for his work. Our belief that Mark extensively reworked Luke in the course of retelling the Gospel stories in no way detracts from this conclusion. A master craftsman always chooses to work with the best materials available. A master chef always chooses the finest ingredients with which to prepare a dish. The same holds true for the author of Mark’s decision to use the Gospel of Luke as the raw material for his re-telling of the story of Jesus.

Robert Lindsey believed that one of the editorial techniques the author of Mark employed in his rewriting of Luke was to pick up words and phrases from other sources and to incorporate them into his revised version of the Gospel stories. In a newly released excursus to The Life of Yeshua: A Suggested Reconstruction we have begun to catalog these “Markan pick-ups.”[1] Lindsey traced the sources of the Markan pick-ups to the non-Markan portions of Luke, to Acts, to the Epistles of Paul, and to the Epistle of James. In other words, in addition to using the Gospel of Luke as the primary source for his Gospel, the author of Mark also used other writings that are now included in the New Testament to spice up his storytelling. We will discuss the reason why the author of Mark might have done this in a moment. But first we should consider what this tells us about the sources of the Markan pick-ups. What it tells us is that the author of Mark held these writings–Acts (which was written by the author of Luke), the Pauline Epistles, and the Epistle of James–to be of equal quality and authority as the Gospel of Luke. Mark’s estimation of these writings was probably also shared by the community (or communities) to whom his Gospel was addressed. The Gospel of Mark might, therefore, be extremely early evidence of what we might refer to as a proto-canon that contains an already sizable portion of what later became the New Testament.

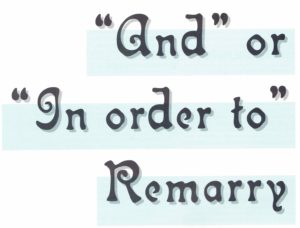

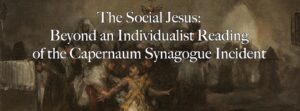

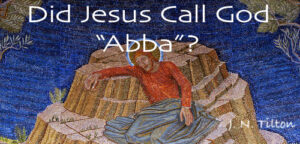

The author of Mark composes his Gospel. Behind him is a lion, which is the symbol of the Gospel of Mark in Christian iconography. This illumination is in the Gospels from Mainz, which belongs to the manuscript collection of the Koninklijke Bibliotheek in The Hague (The National Library of the Netherlands).

His willingness to use both the writings of Paul and the Epistle of James also suggests that, at least for the author of Mark and the communities for whom he wrote, the rift between the Jewish-Christian perspective expressed in the Epistle of James and the pro-Gentile perspective expressed by Paul was not irreconcilable. At a very early stage, when the issue of Jewish-Christian and Gentile-Christian relations in the Church was still a live issue, the author of Mark regarded the opinions of Paul and the author of James as complimentary and equally authoritative. This in turn suggests that the picture of harmony and mutual respect between Paul and James that is described in Acts has a more solid historical basis than some scholars have been willing to allow.

Returning to the motivations behind the Markan pick-ups, it appears that the author of Mark endeavored by means of these pick-ups to create links between the story of Jesus and the experiences of his later followers. Lindsey believed that Mark often used vocabulary from the miracle stories in Acts in his retelling of the miracle stories of Jesus in order emphasize the continuity that exists between Jesus’ actions and the deeds that were performed in the early Church. In a similar manner, Mark used vocabulary from the Epistles of Paul and James to enrich his reiteration of Jesus’ teachings in order to show that the teachings of these two leaders of the Church were already inherent in Jesus’ message.

This observation brings us to the final positive remark I want to make about the Gospel of Mark. If Lindsey’s theories about the sources and motivations behind the Markan pick-ups are correct, then this reveals a strongly pastoral instinct at the core of Mark’s Gospel. If it was the goal of the author of Mark to create echoes and resonances between the story of Jesus and the experiences of Jesus’ later followers, then we must conclude that Mark’s editorial activity was not capricious or irresponsible, but was guided by a concern that the readers of his Gospel would be able to see themselves in the stories about Jesus. Every good pastor wants his or her congregation to feel a deep sense of unity with Jesus’ story so that Jesus’ story will shape and inform the congregation’s experience. Mark attempted to achieve this goal by retelling the stories about Jesus in such a way that his readers could identify themselves inside the story. In this way the author of Mark helped his readers to perceive Jesus’ story continuing in their own lives and experiences. What higher praise could an evangelist hope for than that?

- [1] See Joshua N. Tilton and David N. Bivin, “LOY Excursus: Catalog of Markan Stereotypes and Possible Markan Pick-ups.” ↩