Revised: 18-August-2017

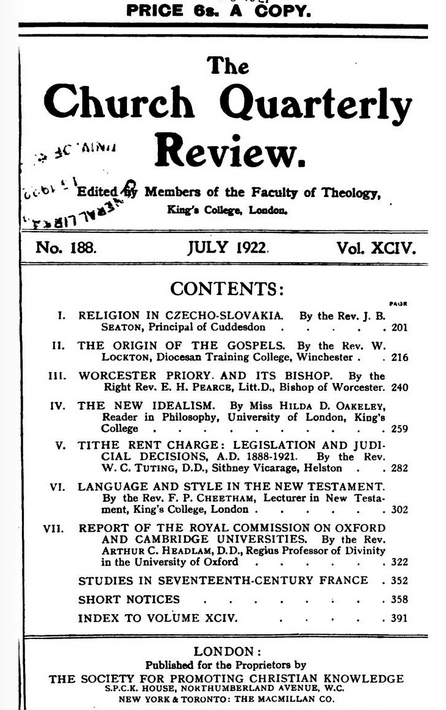

Front cover of the issue of The Church Quarterly Review in which Lockton’s groundbreaking article, “The Origin of the Gospels” appeared.

The Significance of Lockton’s Work for Lindsey’s Synoptic Theory

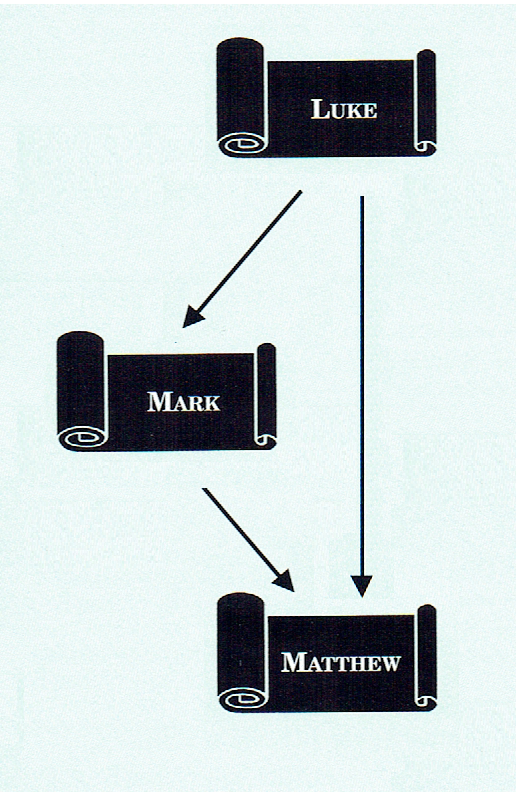

Decades later, Robert Lindsey independently arrived at conclusions similar to Lockton’s. Like Lockton, Lindsey realized that the Gospel of Luke is the earliest of the Synoptic Gospels, that Mark reworked Luke, and that Matthew relied on Mark.

When he came to his solution to the Synoptic Problem in 1962, however, Lindsey was initially skeptical of his own theory since he had never heard of any scholar who had suggested that the Gospel of Luke was written prior to the Gospel of Mark.[2] Reflecting on his breakthrough moment, Lindsey wrote:

When I discovered that Mark, in writing his account, had used the Gospel of Luke, my knowledge of the history of the Synoptic Problem was very limited. Perhaps this was fortunate, for I began to explore scholarly literature to see if anyone else had suggested that Luke was the first-written of the Synoptic Gospels. After considerable searching, I found in McNeile’s An Introduction to the Study of the New Testament a note stating that William Lockton had proposed [JP editors: in The Church Quarterly Review] that “Mark was formed out of Luke, the earliest Gospel, and Matthew out of both Luke and Mark.” This was all, the barest reference, and I was thousands of miles from the nearest copy of The Church Quarterly Review, published in England.[3]

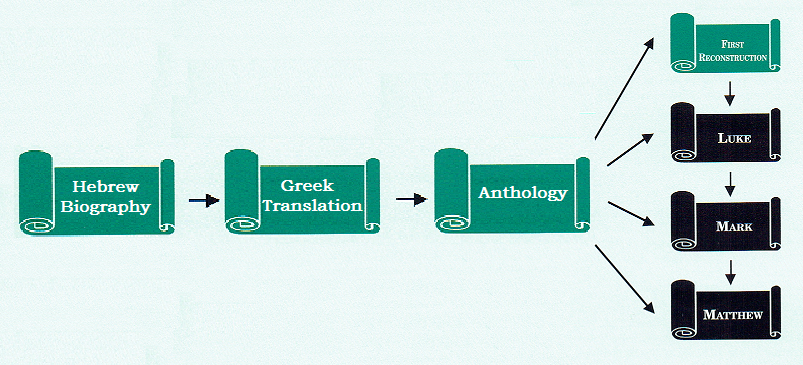

Eventually, with the help of a friend in England, Lindsey was able to obtain a detailed summary of Lockton’s article. Lindsey was struck by Lockton’s emphasis on the importance of the “minor agreements,” and especially by his analysis of Jesus’ eschatological discourse recorded in Luke 21, Mark 13 and Matthew 24. Lockton’s research was independent confirmation of the correctness of Lindsey’s theory that “Luke is first” and that the order of the writing of the Synoptic Gospels is Luke → Mark → Matthew.[4] Nevertheless, Lindsey’s hypothesis differed from Lockton’s in one significant respect: whereas Lockton believed that Mark and Matthew had copied Luke, Lindsey believed that the author of Matthew had no knowledge of Luke, but rather depended on one of Luke’s sources.

Lindsey’s Theory of the Transmission of Synoptic materials from the conjectured Hebrew source down to the canonical Gospels of Matthew, Mark, and Luke.

Emboldened by the confirmation from Lockton’s work and encouraged by his friend, Professor David Flusser of the Hebrew University, who was convinced that Lindsey’s theory had merit, Lindsey published his preliminary findings in an article entitled “A Modified Two-Document Theory of the Synoptic Dependence and Interdependence” in the journal Novum Testamentum in the autumn of 1963.[5] In the years that followed Lindsey continued to refine and defend his hypothesis in books and articles, most of which can be found on JerusalemPerspective.com.[6]

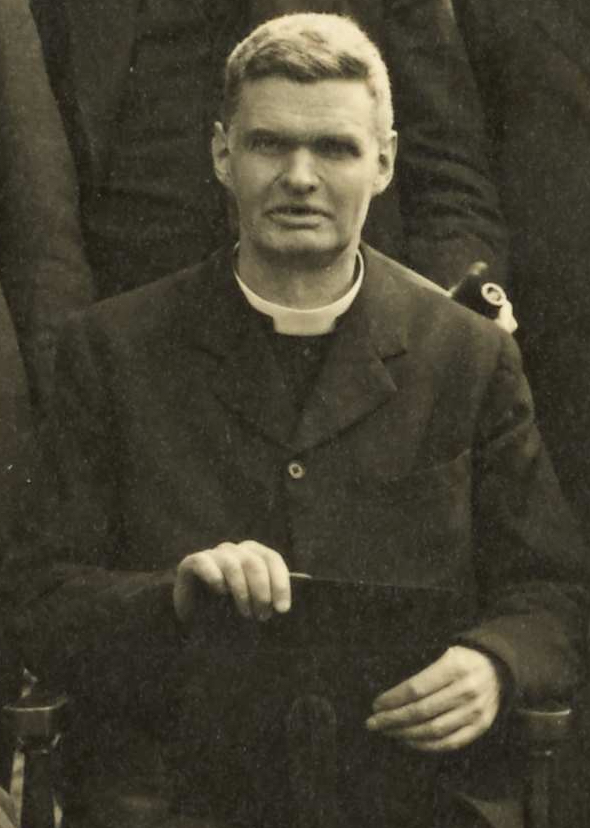

William Lockton in 1911, age 32. (Detail from photograph by Salmon of Winchester: Hampshire Record Office: University of Winchester Archive: 47M91W/Q5/1/10.)

The Biography of William Lockton

Since Lockton’s discovery was so important to Lindsey, it is only natural that Lockton’s life, as well as his research, should be of interest to those who subscribe to Lindsey’s synoptic hypothesis. The following is a brief biography of Lockton published by his alma mater, Cambridge University:

LOCKTON, WILLIAM. Adm. pens. at ST JOHN’S, Aug. 17, 1897. S. of Henry Herbert, formerly police-sergeant, of Shepshed, Leics. [and Clara Woolley]. B. Nov. 23, 1878, at Kegworth. Schools, Loughborough Grammar (Rev. J. P. Polgrave) and Grantham Grammar (Mr W. J. Hutchings). Matric. Michs. 1897; Scholar, 1897; Lady Kay Scholar; B.A. 1900. Migrated to Jesus, Oct. 1900; M.A. 1904. B.D. 1920, from St John’s. Ord. deacon (Exeter) 1902; priest, 1903; C. of St Matthew’s Exeter, 1902-10. Vice-Principal of St Peter’s College, Peterborough, 1914-15. Lecturer and Assistant Chaplain at Saltley College, Birmingham, 1915-16. Assistant Master at Denstone College, 1916-19. Vice-Principal and Assistant Chaplain at Winchester Diocesan Training College, 1910-36. Author, The Remains of the Eucharist; The Three Traditions in the Gospels; Divers Orders of Ministers, etc. Resided latterly at Loughborough, where he died Feb. 12, 1937. (Crockford; The Times, Feb. 15, 1937.) (Alumni Cantabrigienses: A Biographical List of All Known Students, Graduates and Holders of Office at the University of Cambridge from the Earliest Times to 1900, Part II: From 1752 to 1900: Volume IV: Kahlenberg-Oyler [compiled by J. A. Venn; Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1951], p. 197.)[7]

• On the title pages of his books, Lockton lists himself as “Vice-principal and Lecturer in Mathematics, Winchester Diocesan Training College.”[8]

• In addition to his works on the Synoptic Gospels, Lockton wrote at least one more article and two books:

◦ The Treatment of The Remains at the Eucharist after Holy Communion and The Time of the Ablutions, with an Appendix on Reservation and the Book of Common Prayer (Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press and Macmillan, 1920).[9]

◦ Divers Orders of Ministers: An Inquiry into the Origins and Early History of the Ministry in the Christian Church (London: Longmans, Green and Co., 1930).

One might puzzle over how an Anglican priest and vice-principal of a diocesan training college could make such significant discoveries in the field of synoptic research. Lockton’s biography provides the answer: Lockton was highly educated in Scripture with B.A., M.A. and BD degrees from various colleges of Cambridge University, one of the two best universities in England in Lockton’s day. Perhaps Lockton’s training in mathematics also was key to coping with the “synoptic problem,” one of the most complex subjects in New Testament scholarship.

- [1] William Lockton, “The Origin of the Gospels,” The Church Quarterly Review 94 (1922): 216-239. Click here to read Lockton’s “The Origin of the Gospels,” recently reissued at JerusalemPerspective.com. ↩

- [2] In scholarship, if a researcher has a novel idea or insight that no one else has ever had, that idea or insight is suspect. The same is true of Synoptic Gospel source theories such as Lindsey’s. ↩

- [3] Robert L. Lindsey, “Introduction to A Hebrew Translation of the Gospel of Mark,” under the subheading “Confirming the Priority of Luke.” ↩

- [4] The importance of Lockton’s research for Lindsey is evident from the “starring role” Lockton plays in Lindsey’s account of his breakthrough in “Introduction to A Hebrew Translation of the Gospel of Mark,” especially under the subheading “The Confirmation of Lockton’s Work.” ↩

- [5] See Robert L. Lindsey, “A Modified Two-Document Theory of the Synoptic Dependence and Interdependence,” Novum Testamentum 6.4 (1963): 239-263. A revised and updated version of this article is now available at JerusalemPerspective.com: “A New Two-source Solution to the Synoptic Problem.” ↩

- [6] See Robert L. Lindsey, “A New Approach to the Synoptic Gospels”; idem, “Unlocking the Synoptic Problem: Four Keys for Better Understanding Jesus”; idem, “Measuring the Disparity Between Matthew, Mark and Luke.” ↩

- [7]

Expanded version of Lockton’s above biography:

Lockton, William.

Adm[itted as a] pens[ioner] at ST JOHN’S, Aug. 17, 1897.

S[on] of Henry Herbert, formerly police-sergeant, of Shepshed, Leic[e]s[tershire] [and Clara Woolley].

B[orn] Nov. 23, 1878, at Kegworth [Leicestershire].

Schools, Loughborough Grammar [Leicestershire] (Rev. J. P. Polgrave) and Grantham Grammar [Lincolnshire] (Mr W. J. Hutchings). Matric[ulation] Mich[aelma]s 1897;

Scholar, 1897; Lady Kay Scholar; B.A. 1900.

Migrated [i.e., transferred] to Jesus [College, Cambridge. U.], Oct. 1900;

M.A. 1904. B.D. 1920, from St John’s [College, Cambridge. U.].

Ord[ained] deacon (Exeter [Devon]) 1902; [Ordained] priest, 1903;

C[anon] of St Matthew’s Exeter [Devon], 1902-10.

Vice-Principal of St Peter’s College, Peterborough [Northamptonshire], 1914-15.

Lecturer and Assistant Chaplain at Saltley College, Birmingham [Warwickshire], 1915-16.

Assistant Master at Denstone College [Staffordshire], 1916-19.

Vice-Principal and Assistant Chaplain at Winchester Diocesan Training College [Winchester, Hampshire], 1910-36.

Author, The Remains of the Eucharist; The Three Traditions in the Gospels; Divers Orders of Ministers, etc.

Resided latterly at Loughborough [Leicestershire], where he died Feb. 12, 1937. (Crockford; The Times, Feb. 15, 1937.) ↩ - [8] The Winchester Diocesan Training School, which was founded in 1840 as “a Church of England foundation for the training of elementary schoolmasters,” later evolved into the University of Winchester. See http://www.winchester.ac.uk/aboutus/Pages/Ourhistory.aspx; https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/University_of_Winchester. ↩

- [9] Before writing this book, Lockton first wrote an article on the subject, “The Eucharistic Prayer,” The Church Quarterly Review (July 1918), just as in 1922 he wrote an article on the Synoptic Problem before writing his first book on the subject. ↩