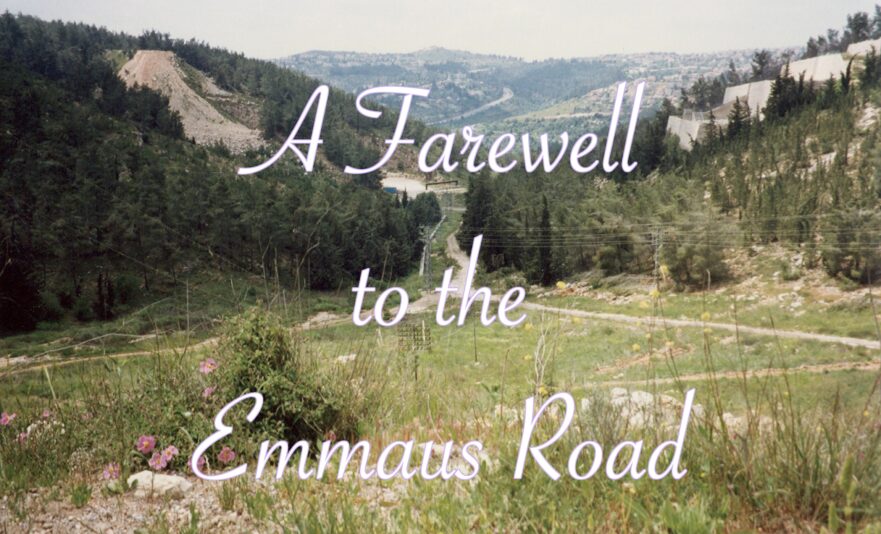

How to cite this article: David N. Bivin, “A Farewell to the Emmaus Road,” Jerusalem Perspective (2017): [https://www.jerusalemperspective.com/16208/].

| Rather listen instead? |

| JP members can click the link below for an audio version of this essay.[*]

Paid Content

Premium Members and Friends of JP must be signed in to view this content. If you are not a Premium Member or Friend, please consider registering. Prices start at $5/month if paid annually, with other options for monthly and quarterly and more: Sign Up For Premium  |

Revised: 26 March 2019

The Emmaus Road narrative is the climax of Luke’s Gospel. In it, two of Jesus’ disciples encounter their resurrected Lord as they follow the road leading west from Jerusalem. Not only do the hearts of the disciples burn as they speak with their risen Master, the hearts of the readers burn as well, since, unlike the disciples, we know that it is Jesus himself who is accompanying them as the disciples relate the sad tale of how all their hopes for the redemption of Israel were dashed when Jesus was crucified outside the walls of the holy city. Readers feel almost as if they were present with the disciples on the road as Jesus walked and spoke with them.

Premium Members and Friends of JP must be signed in to view this content.

If you are not a Premium Member or Friend, please consider registering. Prices start at $5/month if paid annually, with other options for monthly and quarterly and more: Sign Up For Premium

Searching for Luke’s Emmaus

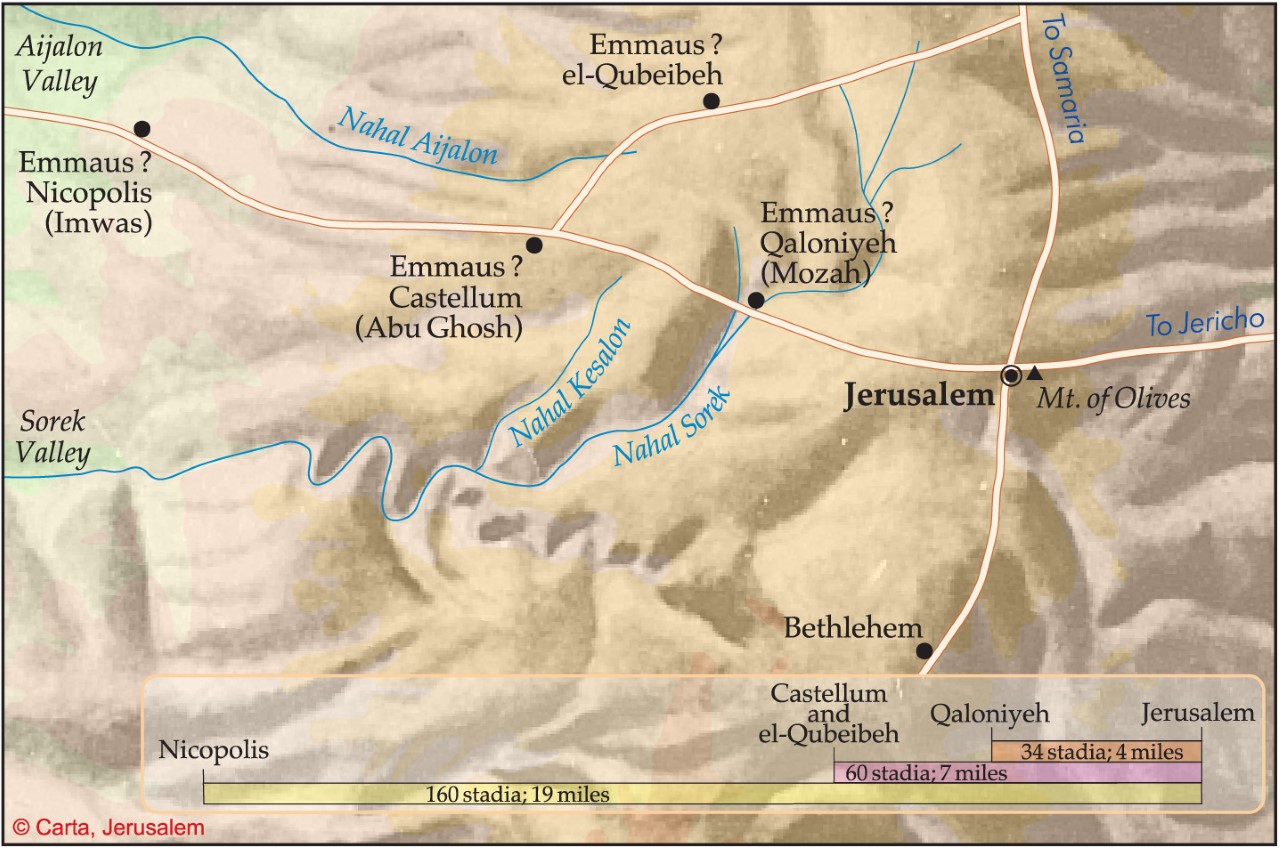

Although a tradition emerged during the Byzantine period identifying Emmaus-Nicopolis as the Emmaus mentioned in Luke 24:13,[7] the distance of this site from Jerusalem (some nineteen miles) contradicts the information given in the Gospel account. Luke described the disciples as going down from Jerusalem to Emmaus and back again to Jerusalem on the same day (Luke 24:33). But disciples traveling by foot would have been hard pressed to cover in a single day the thirty-eight mile round trip necessitated by an identification of Luke’s Emmaus with Emmaus-Nicopolis. Moreover, Luke 24:13 explicitly states that the distance to Emmaus was sixty stadia, that is, only about seven miles from Jerusalem.[8] Therefore, despite the strong and relatively early Christian tradition equating Emmaus-Nicopolis with Luke’s Emmaus, this identification is unlikely to be correct.

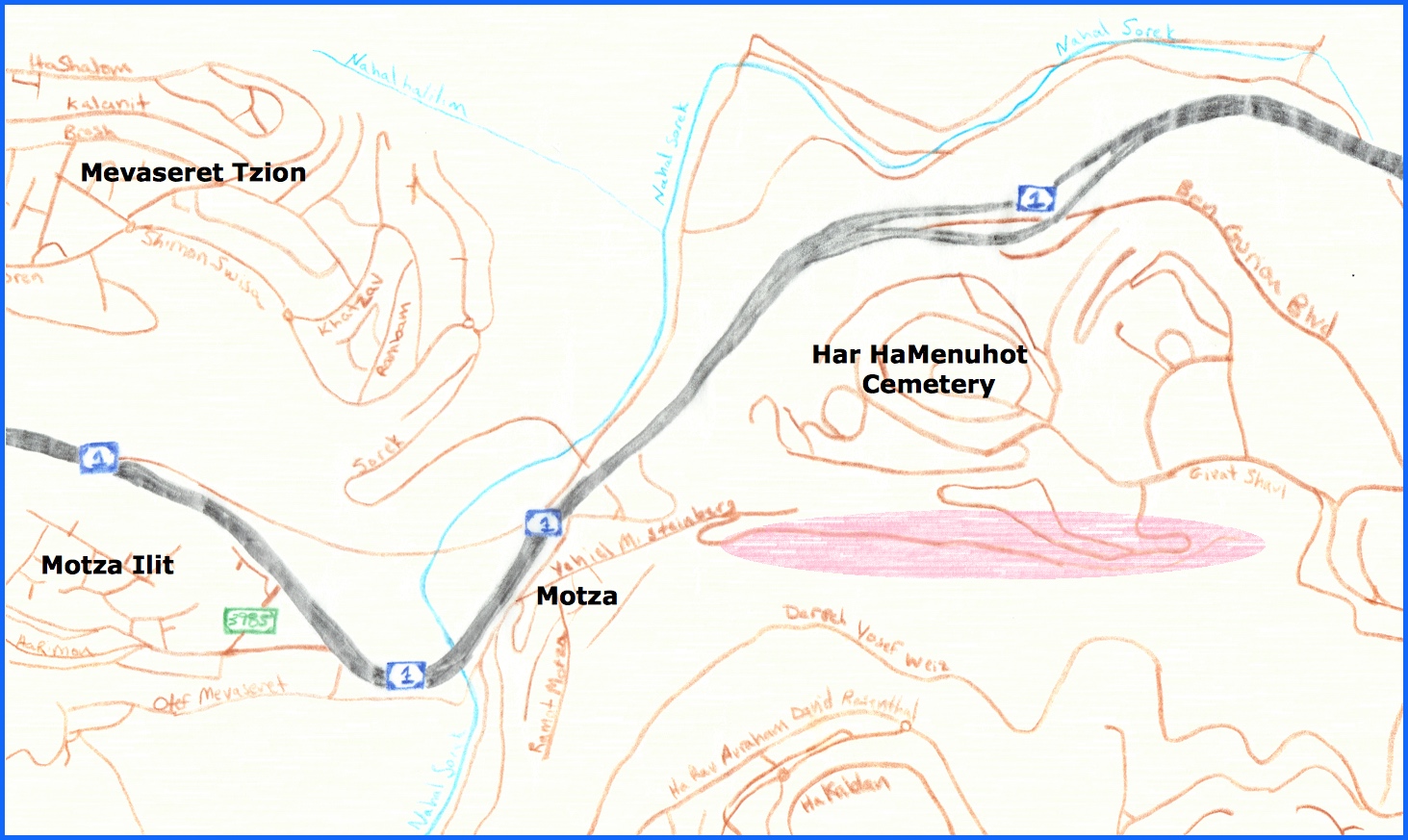

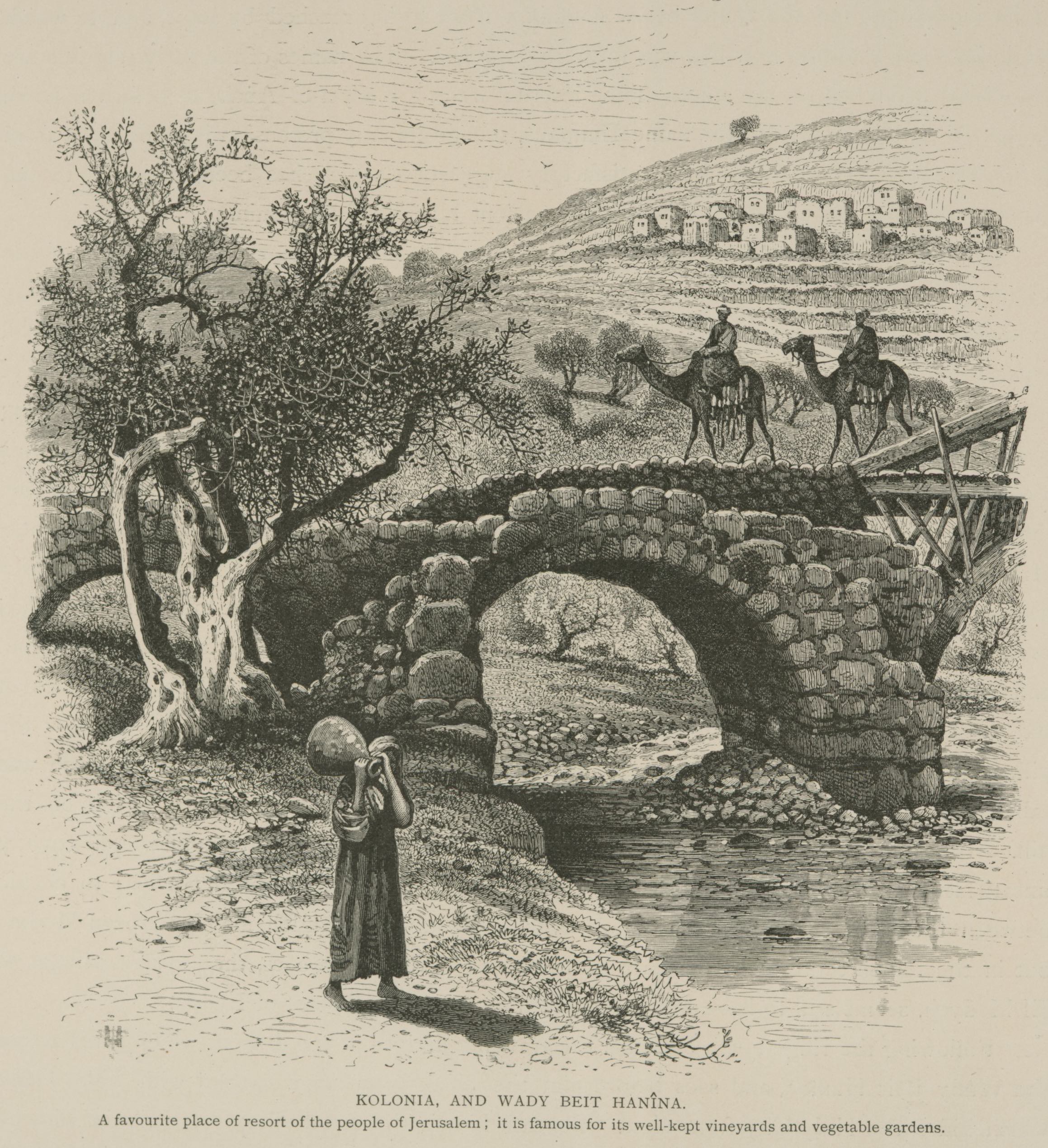

Four proposed locations of Luke’s Emmaus. Nicopolis was favored in the Byzantine period and still has its supporters among scholars. Castellum (Abu Ghosh) and el-Qubeibeh were favored in the Crusader period and are approximately located 60 stadia from Jerusalem, the distance indicated in Luke. Qaloniyeh (Qalunya)-Motza has recently found support among a handful of leading scholars. Map courtesy of Carta Jerusalem, used here with permission.

There was, however, another Emmaus that was known to have existed in the Second Temple period, and this second Emmaus fits the information presented in Luke’s Gospel far more comfortably than Emmaus-Nicopolis. Josephus reports that after Jerusalem fell to the Romans in 70 C.E. and the rebellion was suppressed, the Roman emperor Vespasian set aside land near Jerusalem as a settlement for veteran Roman soldiers:

About the same time Caesar sent instructions to Bassus and Laberius Maximus, the procurator, to farm out all Jewish territory. For he founded no city there, reserving the country as his private property, except that he did assign to eight hundred veterans discharged from the army a place [χωρίον] for habitation called Emmaus [ὃ καλεῖται μὲν Ἀμμαοῦς], distant thirty stadia from Jerusalem. (J.W. 7:216-217; Loeb, adapted)

The information regarding this second Emmaus accords well—though not perfectly—with the details of Luke’s narrative. Unlike Emmaus-Nicopolis, which Josephus referred to as a πόλις (polis, “city”), Josephus calls this other Emmaus a χωρίον (chōrion, “place,” “field”), which is closer to Luke’s description of Emmaus as a κώμη (kōmē, “village”). The distance Josephus measures between this Emmaus and Jerusalem (about three and a half miles) also fits with Luke’s description of the disciples making the journey to Emmaus from Jerusalem and back again on the same day.

Nevertheless, one hitch remains. While Josephus states that this Emmaus was thirty stadia distant from Jerusalem, Luke 24:13 measures the distance as sixty stadia, twice the distance reported by Josephus. This discrepancy might be overcome, however, if we were to suppose that Luke cited the entire distance the disciples traveled the day of Jesus’ resurrection on their round trip from Jerusalem to Emmaus and back again, instead of the distance between the two locations.[9]

A rabbinic discussion of the Feast of Tabernacles celebrations that were observed in the days of the Second Temple sheds additional light on the Emmaus described in Luke 24:13 and J.W. 7:217:

The commandment of the willow branch: how was it carried out? There was a place [מָקוֹם, māqōm] below Jerusalem called Motza [מוֹצָא, mōtzā’]. They went down there and gathered from there willow branches and brought them and stood them up on the sides of the altar and their tops bowed over the altar…. (m. Suk. 4:5)

Commenting on this mishnah, the Jerusalem Talmud adds that according to Rabbi Tanhuma, a fourth-century C.E. sage, “Kalonya [קָלוֹנְיָיא, qālōnyyā’] was its [i.e., Motza’s—DNB] name” (y. Suk. 4:3 [18b]).[10] The Babylonian Talmud ascribes the same statement to an anonymous tannaic authority (i.e., a baraita), adding that the name Motza was derived from Kalonya’s exemption from imperial taxation (b. Suk. 45a).

Steps leading down to one of Motza’s springs. Each year orthodox Jews come here to get water for baking their matzah for the Feast of Unleavened Bread. Photographed by Lucinda Dale-Thomas, spring 1992.

This rabbinic evidence is invaluable for identifying the location of Luke’s Emmaus for three reasons. First, the name Kalonya and its tax-exempt status connects the Mishnah’s Motza to Josephus’ second Emmaus, the one that became the location of a Roman veteran’s settlement. This is because the most plausible explanation of the name Kalonya is that it comes from the Latin word colonia (“colony”),[11] a term that could have loosely applied to a veteran’s settlement. Moreover, a tax exemption would have been a natural incentive to encourage the Roman veterans of the war to settle the area.[12] Second, if the Emmaus-Motza-Kalonya identification is accepted, the Mishnah’s evidence of a Jewish presence at Motza lends credibility to Luke’s account of disciples traveling, perhaps even returning home, to Emmaus.[13] Archaeological discoveries also indicate a late Second Temple-period Jewish presence at Motza.[14] Third, the rabbinic description of Motza as merely a מָקוֹם (māqōm, “place”) matches Josephus’ characterization of Emmaus as a χωρίον (chōrion, “place”), both of which are compatible with Luke’s reference to Emmaus as a κώμη (kōmē, “village”). Thus, the combined evidence from Luke’s Gospel, Josephus and rabbinic literature strongly supports the identification of Luke’s Emmaus with Motza-Kalonya.

| Luke | Josephus | Rabbinic Literature | |

| Place Name: | Emmaus (Ἐμμαοῦς) | Emmaus (Ἀμμαοῦς) | Motza (מוֹצָא) |

| Description: | village (κώμη) | place (χωρίον) | place (מָקוֹם) |

| Distance from Jerusalem: | 60 stadia (round trip?) | 30 stadia | “Below Jerusalem,” evidently within easy walking distance. |

| Status: | Became a veterans’ settlement. | Called Kalonya (קָלוֹנְיָיא, “colony”). |

The “place below Jerusalem called Motza” referred to in the Mishnah is mentioned as early as the book of Joshua, where it is assigned to the tribal allotment of Benjamin. The book of Joshua refers to Motza as הַמֹּצָה (hamotzāh, “the Motza”; Josh. 18:26), spelled with a final ה instead of an א as in the Mishnah, and with the definite article prefixed to the name.[15] Whereas the translators of the Septuagint rendered ha-Motza in Josh. 18:26 as Αμωσα (Amōsa),[16] Josephus appears to have transliterated ha-Motza as Ἀμμαοῦς (Ammaous).[17] If this analysis of the name Ἀμμαοῦς is correct, then Luke’s Ἐμμαοῦς (Emmaous, “Emmaus”) is best understood as an independent transliteration of ha-Motza, again with the definite article, which the author of Luke found in his written source.

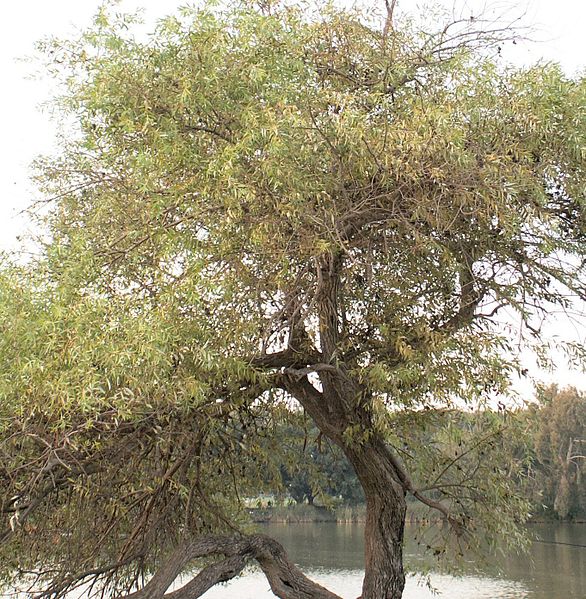

A willow tree (salix acmophilla). Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

The Mishnah’s association of Motza with willow trees suggests that the name “Motza,” literally “that which brings forth,” refers to the springs that water the valley where Motza is located, since willows prefer to grow in places where there is a permanent source of water.[18] The word מוֹצָא (mōtzā’) in the sense of spring is attested, for example, in Isaiah 41:18, which refers to מוֹצָאֵי מָיִם (mōtzā’ē māyim, “springs of water”). Doubtless the Romans chose to found a colony at Motza in part because of the permanent springs that watered the valley there. The Romans must also have been attracted to this location by the fact that just to the north of Motza the valley broadens, offering a pleasant and spacious area for settlement. Since the valley was well watered and had rich soil, it was an excellent spot for agricultural development. Another advantage of Motza’s location that made it suitable for a Roman veterans’ colony was its strategic position protecting the ascent to Jerusalem on the road leading from Jaffa.[19]

If the identification of Luke’s Emmaus with the Emmaus mentioned by Josephus as the location of a Roman colony is correct, and if the identification of this Emmaus with the Motza-Kalonya known from rabbinic literature is accepted, then we are able to pinpoint the approximate location of Luke’s Emmaus, since the Hebrew-Latin name Kalonya was retained as Qalunya by the Arabic speakers who resided in this location until modern times.[20]

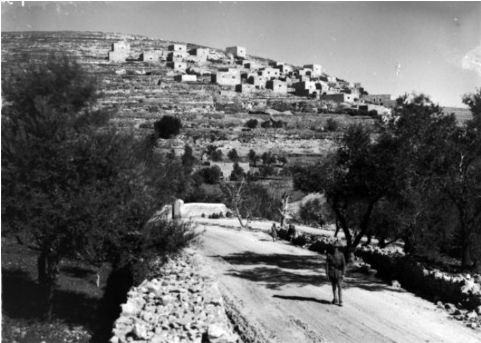

The hilltop village shown in the center of this photo is Motza Illit. On the slopes across the highway from Motza Illit was the Arab village (until 1948) of Qalunya. Photographed by Horst Krüger, February 2003.

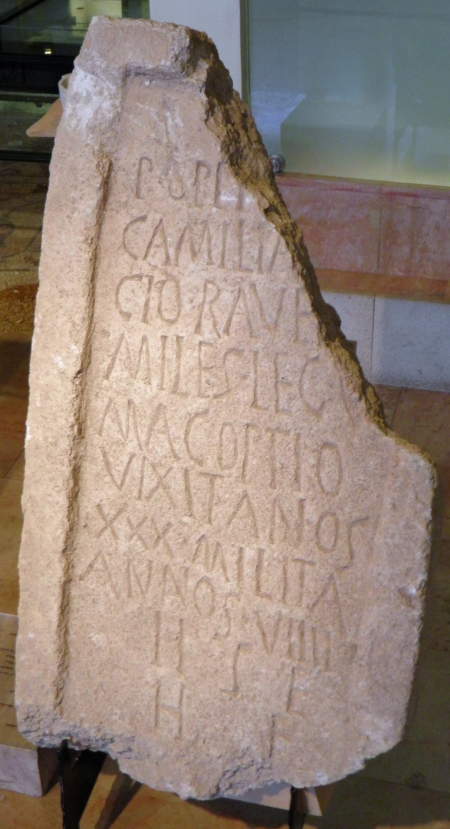

Physical evidence of a Roman presence at Motza-Kalonya is supplied by the remains of an ancient Roman bath,[21] and a Roman tombstone adorned with the bust of a girl and bearing a Latin inscription.[22] Regarding this tombstone, Fischer, Isaac and Roll state, “In the eastern Roman provinces the use of Latin on private inscriptions is typical of genuine (as opposed to titular) veteran settlements…. It is, in fact, so rare that this inscription may be considered important additional confirmation of the identity of Motza with Vespasian’s veteran settlement.”[23]

My Experiment

An aerial view of the Motza neighborhood photographed by Moshe Milner. Courtesy of Israel’s National Photo Collection.

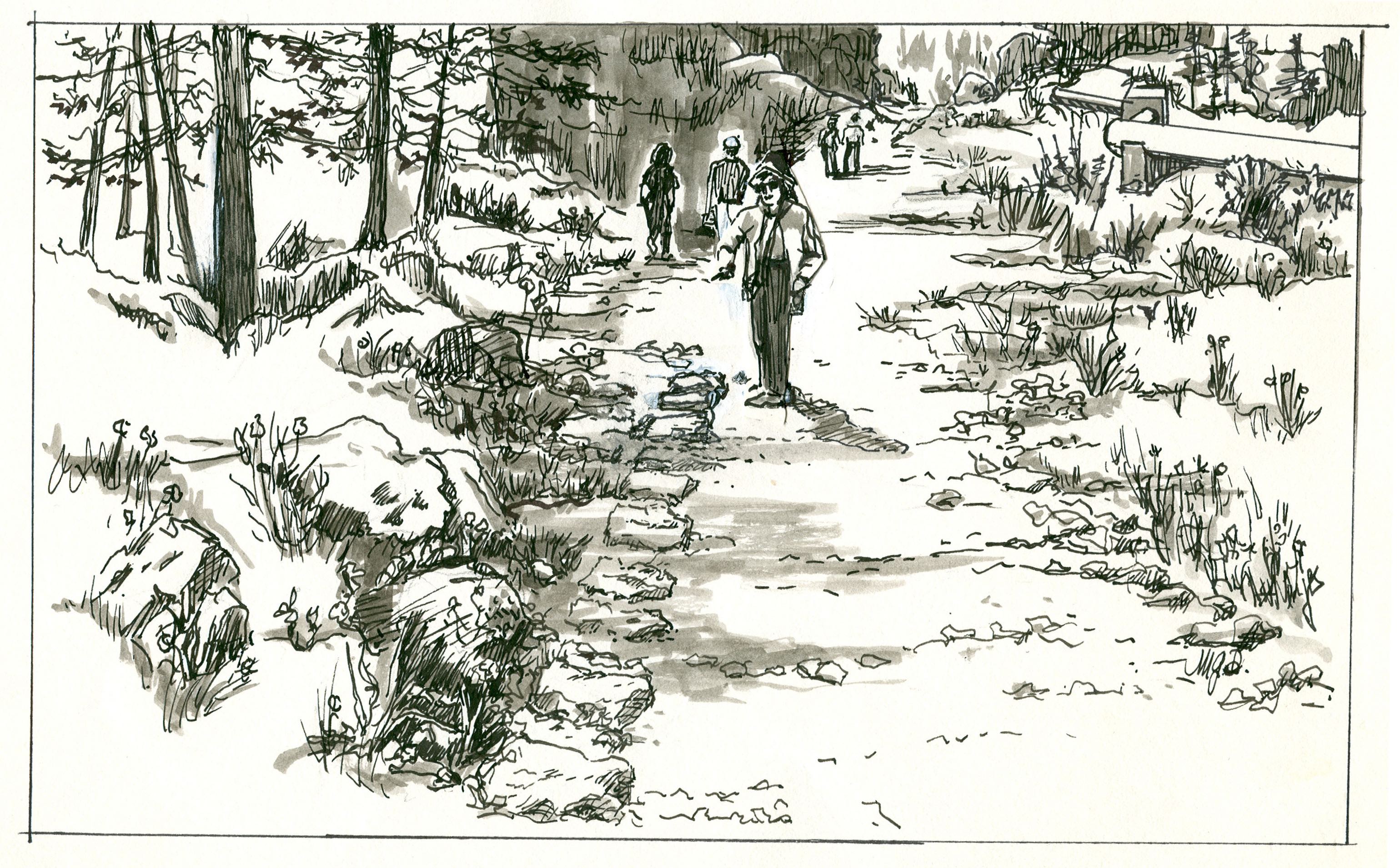

Because I found the above-cited evidence regarding the location of Luke’s Emmaus at Motza-Qulonya to be compelling, I conducted an experiment to put this hypothesis to the test. On October 2nd of the year 1987, I walked with my son Natan from the Western Wall of the Temple Mount (the Kotel) to the springs at Motza following the route of the Roman road (on which, see below) as closely as possible in order to measure how long such a journey would take. It was the eve of Yom Kippur, so no vehicles were moving on the streets to slow us down, and we set out from the Western Wall at 6:10 p.m. under a full moon, walking at a leisurely pace. Together we covered the distance from the Western Wall to the Motza springs in one hour and twenty minutes.[24] My experiment proves that Jesus’ disciples could easily have made the trip down from Jerusalem to Motza-Emmaus and back again within the time frame Luke describes. According to Luke, the two disciples who were heading to Emmaus set out from Jerusalem sometime after morning, for they knew of the women’s report of the empty tomb (Luke 24:22-24), but it could have been as late as mid-afternoon. The disciples did not head back to Jerusalem until after they had sat down for their evening meal in Emmaus (Luke 24:29, 33).

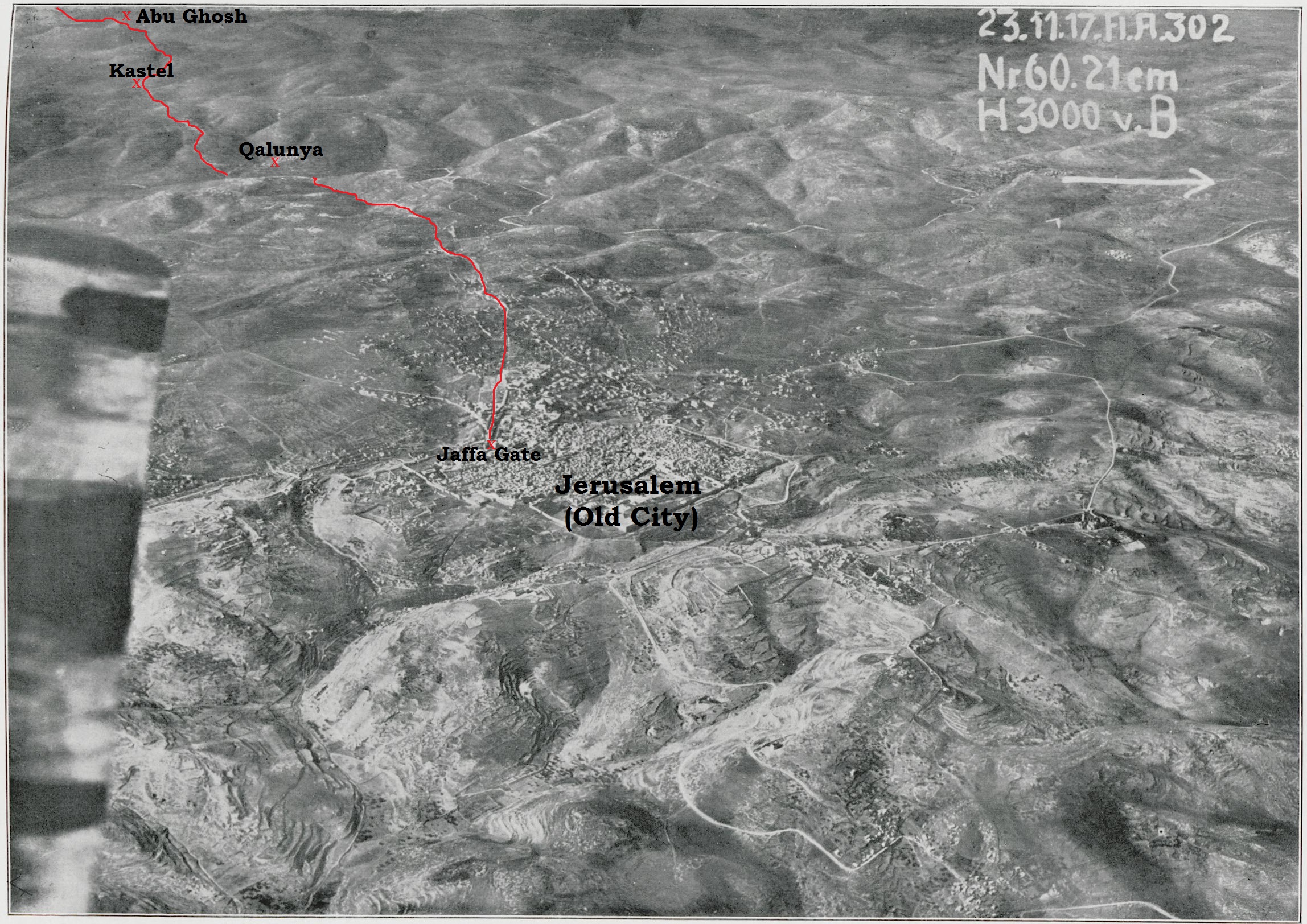

Aerial photograph of Jerusalem’s environs from Gustaf Dalman’s Hundert deutsche Fliegerbilder aus Palästina (Gütersloh: Bertelsmann, 1925). Superimposed on the photograph is the approximate route of the Emmaus-Jerusalem road marked in red. Part of the route is hidden from view as the road descends into the valley as it approaches Qalunya.

The Roman Road

View from the hill upon which the Arab village of Qalunya was situated facing east toward Jerusalem up the valley through which the road to Emmaus once ran. The Har Hamenuhot cemetery, the light colored structure in the center of the photo, now dominates the landscape. Photographed by Horst Krüger, February 2003.

Even if readers do not find the identification of Luke’s Emmaus with Motza-Qalunya convincing, we can still agree that the remains of the Roman road that runs down from Jerusalem past Motza to Emmaus-Nicopolis marks the route Jesus and his disciples took to Emmaus on the day of Jesus’ resurrection.[25]

In 2002, the Israel Antiquities Authority (IAA) surveyed the remains of a paved road that led west from Jerusalem to Emmaus-Nicopolis which can still be observed in the vicinity of modern-day Motza.[26] The IAA’s report, which identifies the remains of the road as Roman, states that “the road runs, for most of its length, in the depth of the ravine, and finally, zigzags and ascends next to Har Hamenuhot cemetery.”[27] The road continues east from Motza, through a ravine past the Har Hamenuhot cemetery “to Giv‘at Shaul, to Giv‘at Ram, and through the Jaffa Gate to Jerusalem.”

The pink shading shows the area where the remains of the Roman road from Jerusalem to Emmaus are still (barely) visible.

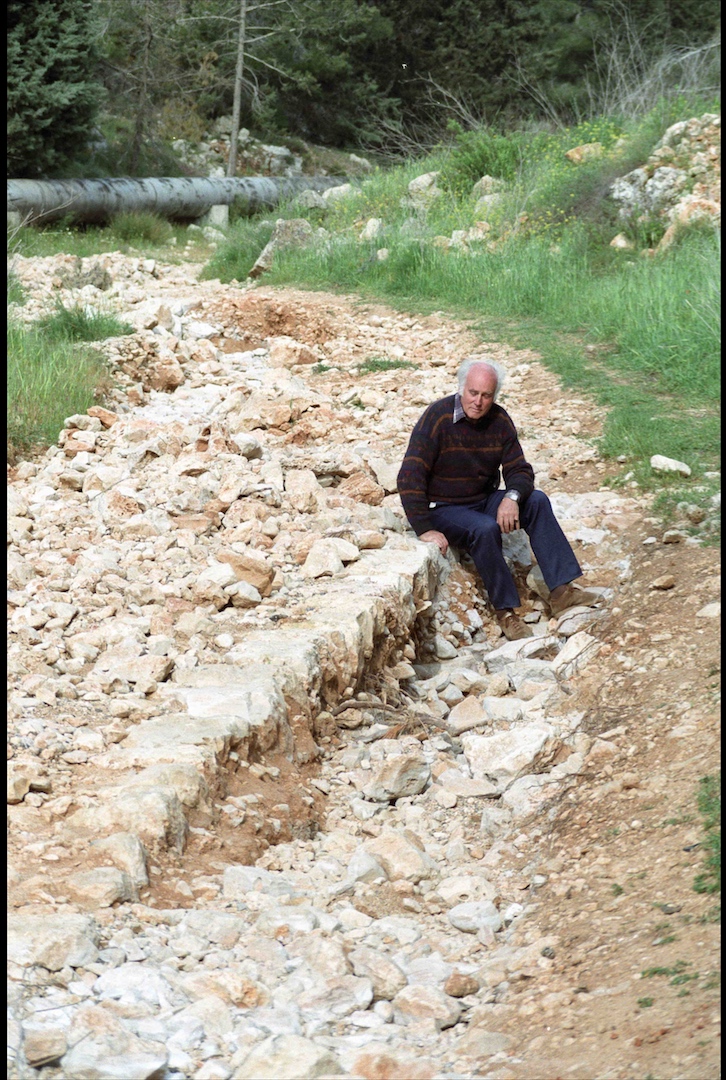

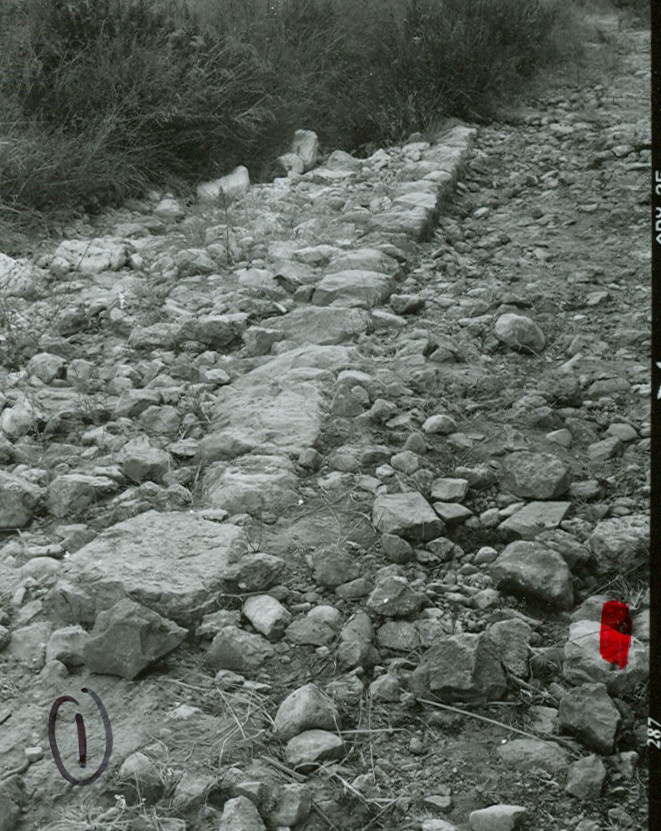

When I measured the remains of the Roman road some twenty years ago, when the remains were much more visible than they are today, I found that the Roman road was about twelve feet (or three meters) wide. According to the IAA’s report: “The road was paved with the usual road-building technique: cleaning and straightening of the route, laying down of the curbstones on the road’s edges, and filling in the space in between them with a layer of foundation stones, upon which the paving was laid. The paving was done, apparently, with the help of flat stones or carved stones that were fitted one to another, or with a layer of gravel, or pebbles, etc. (according to Israel Roll).”

When I first became acquainted with the Roman road near Motza, some of the pavement and many of the curbing stones were still clearly visible. Sadly, over the past recent decades I have watched as the Roman road has fallen prey to severe erosion, such that in many places the remains of the road have been completely obliterated. The IAA’s report notes that the condition of the Roman road is poor, adding that “the road in its present state is torn up, and often it is accompanied by the smell of sewage.” The odor of which the IAA’s report complains, is undoubtedly caused by the sewage pipe, which follows the path of the ancient Roman road.

The Mekorot pumping station, part of the National Water Carrier, located near the village of Ramat Motza that boosts the water piped from Israel’s costal plain to Jerusalem. Part of Mekorot’s “Fourth [Pipe]line.” Photographed by Lucinda Dale-Thomas, spring 1992.

The natural beauty of the Emmaus road was initially marred by the installation of a pumping station and enormous water-main that supplies Jerusalem. Much of the physical damage to the Roman road, however, can be attributed to the expansion of the Har Hamenuhot cemetery, mentioned above. Covering two large hills along the modern highway leading from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem, the cemetery has slowly crept down the southern slope of the southern-most of the hills towards the ravine through which the Roman road ascended from Motza to Jerusalem. During the course of the cemetery’s expansion, huge boulders were knocked down the slope by the unsupervised bulldozers at work above. These boulders crashed into everything in their path, knocking down the forest of 50-year-old cedar and pine trees that once lined the Roman road. The boulders also flattened picnic tables and slides and swings used by children of the families who came to this formerly beautiful spot on recreational outings. The cemetery construction also ruined monuments and memorial plaques honoring those who had donated to Keren Kayemeth LeIsrael (Jewish National Fund) to create the recreational area where the remains of the Roman road are now barely visible.

The series of slides from the years 1992, 1997, 1999, 2003 and 2016 featured below is a testimony to how much of the Roman road has already been irrevocably lost.

Emmaus Road Photos 1992:

Emmaus Road Photos 1997:

Emmaus Road Photos 1999:

Emmaus Road Photos 2003:

Emmaus Road Photos 2007:

Emmaus Road Photos 2016:

Most archaeologists are of the opinion that the network of roads the Romans built in the land of Israel was not constructed prior to the period of the First Jewish Revolt (ca. 70 C.E.), and that the most extensive Roman road construction took place during the reign of Hadrian in the second century C.E.[28] The earliest dated milestone belonging to a Roman road in Israel is from 69 C.E.[29] [29] Despite the probable construction of the Roman road near Motza after the time of Jesus, the route it follows traces the same path Jesus and his two disciples followed to Emmaus. The ravine is so narrow that any road built in it could not have been more than a few meters to the left or right of the path on which Jesus and his disciples walked. It is therefore a shame to see the remnants of this potent reminder, which has withstood the passing of so many centuries, disappearing so dramatically in so short a time.

Farewell

The IAA’s report on the Roman road near Motza states that although “the road has been badly damaged, with proper restoration there exists a high potential for developing the road as a scenic route for hikers (‘pilgrims’) from Motza to Jerusalem.” Fourteen years on from the writing of the IAA’s report, the window of opportunity for this dream to be realized is closing rapidly. I fear that soon we may have to bid the Emmaus road a final farewell. Perhaps it is a good reminder that what is built by flesh and blood has its season and then is no more, while those whom Heaven has acclaimed endure forever.

|

I wish to express my gratitude to Professor Ronny Reich and Dr. Stephen J. Pfann for directing me to useful resources on Roman roads in general, and concerning the Emmaus road in particular. I would also like to thank all those who contributed photographs to this article including Gary Alley, Gary Asperschlager, Lucinda Dale-Thomas, Chris deVries, Horst Krüger, Diane Marroquin, Joshua N. Tilton, Israel’s National Photo Collection (Photography Dept. of the Government Press Office), the Classical Numismatic Group and Wikimedia Commons. Special thanks are due to Carta Jerusalem for allowing me to use their map of the various possible locations of Luke’s Emmaus.. In addition, I would like to thank Brian Becker for making the slideshows, which are such an essential part of this article, possible on JP’s website. Finally, I wish to thank Joshua N. Tilton for his assistance in preparing this article for publication. |

- [1] Among the many scholars who have weighed in on the debate are, Stanley A. Cook, “Emmaus,” in Encyclopaedia Biblica (4 vols.; London: Adam and Charles Black, 1899-1903), 2:1289-1290; William Sanday, Sacred Sites of the Gospels (Oxford: Clarendon, 1903), 30-31; Kirsopp Lake, The Historical Evidence For the Resurrection of Jesus Christ (London: Williams & Norgate; New York: Putnam & Sons, 1907), 99-100; Gustaf Dalman, Sacred Sites and Ways: Studies in the Topography of the Gospels (trans. Paul P. Levertoff; New York: MacMillan, 1935), 230; Emil Schürer, The History of the Jewish People in the Age of Jesus Christ (175 B.C.–A.D. 135) (ed. Geza Vermes, Fergus Millar and Matthew Black; Edinburgh: T. & T. Clark, 1973), 1:512-513, n. 142; John Wilkinson, Jerusalem as Jesus Knew It: Archaeology as Evidence (London: Thames and Hudson, 1978), 162-164; Richard M. Mackowski, “Where Is Biblical Emmaus?” Science et Esprit 32.1 (1980): 93-103; Moshe Fischer, Benjamin Isaac and Israel Roll, Roman Roads in Judaea II: The Jaffa-Jerusalem Roads (BAR International Series 628; Oxford: 1996), 222-224; Carsten Peter Thiede, “Where Exactly Is Emmaus?” Israel Today (2002): 15; Anson F. Rainey and R. Steven Notley, The Sacred Bridge: Carta’s Atlas of the Biblical World (Jerusalem: Carta, 2006), 367-68; Paul H. Wright, Greatness Grace & Glory: Carta’s Atlas of Biblical Biography (Jerusalem: Carta, 2008), 197; Hershel Shanks,“Emmaus Where Christ Appeared,” Biblical Archaeology Review 34.2 (2008): 40-80. ↩

- [2] The Shephelah is an intermediate zone of low rolling hills that forms a north-to-south band between the coastal plain and the hill country of Judea. A passage from the Jerusalem Talmud also locates this Emmaus on the boundary between the Shephelah and the coastal plain:

Rabbi Yohanan said: …from Beit Horon to Emmaus [אמאוס] is the mountainous region, from Emmaus to Lod it is Shephelah, from Lod to the sea it is a plain. (y. Sheviit 6:2 [25b])

In the above statement Rabbi Yohanan describes the road that ran south-west from Beit Horon to Emmaus and then turned north-west from Emmaus to Lod along the boundary between the coastal plain and the Shephelah. ↩ - [3] See Jos., J.W. 3:55; Ant. 12:298; 13:15; 14:436; cf. 1 Macc. 9:50. ↩

- [4] Additonal rabbinic sources that may refer to Emmaus-Nicopolis are discussed by Fischer, Isaac and Roll, Roman Roads in Judaea II, 153-155. ↩

- [5] Certainly the Emmaus referred to in the Jerusalem Talmud passage cited in the footnotes above is to be identified with Emmaus-Nicopolis. It is reasonable to suppose that the same Emmaus is referred to in all of the rabbinic passages we have cited. The vocalization אַמְאוּס (’am’ūs) is that given in the Kaufmann codex. Jastrow vocalizes this name as אִמָּאוּס (’imā’ūs) and traces it back to Ἐμμαοῦς / Ἀμμαοῦς, which he takes to be a Hellenized form of חַמְּתָה (ḥametāh, “hot springs”). See Marcus Jastrow, A Dictionary of the Targumim, the Talmud Babli and Yerushalmi, and the Midrashic Literature (2d ed.; New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1903; repr. Peabody, Mass.: Hendrickson, 2005), 74. Other scholars, however, question this derivation. See Fischer, Isaac and Roll, Roman Roads in Judaea II, 151. ↩

- [6] See Mackowski, “Where Is Biblical Emmaus?” 96-97; Fischer, Isaac and Roll, Roman Roads in Judaea II, 153. ↩

- [7] Cf. Eusebius, Onomasticon 90:15; Jerome, Letter 108:8. ↩

- [8] Some New Testament manuscripts read 160 stadia (approximately 19 miles) instead of 60 stadia. This secondary reading appears to be a scribal attempt to conform the biblical text to the tradition that identified Luke’s Emmaus as Emmaus-Nicopolis. See Bruce M. Metzger, A Textual Commentary on the Greek New Testament (London and New York: United Bible Societies, 1975), 184-185; c.f. R. Steven Notley, In The Master’s Steps: The Gospels in the Land (Jerusalem: Carta, 2014), 81-82. ↩

- [9] See Lake, Historical Evidence for the Resurrection, 100; Notley, In the Master’s Steps, 82. ↩

- [10] The sixth-century C.E. monk Cyril of Scythopolis also knew of a place by this name, as he refers in his writings to αἰ πηγαὶ Κολωνίας τε καὶ Νεφθοῦς (“the springs of Kolōnia and Nefthous”; Life of Sabas §67 [ed. Schwartz, 168]). Cited by Fischer, Isaac and Roll, Roman Roads in Judaea II, 223, who state that Nefthous is to be identified as “Nephtoa (Lifta) near Motza, to the NE.” ↩

- [11] See Jastrow, A Dictionary of the Targumim, the Talmud Babli and Yerushalmi, and the Midrashic Literature, 1379; Fischer, Isaac and Roll (Roman Roads in Judaea II, 223) state: “Josephus’ Ammaus must be the same place [as the Kalonya mentioned in the Talmud—DNB] because only a veteran settlement would acquire the name Colonia. Josephus emphasizes that only one such settlement was founded in the area of Jerusalem and there is only one place-name which indicates a connection with veterans in the region.” ↩

- [12] The rabbinic derivation of the name Motza from the verb for tax exemption (יצא) is not a serious etymology, but the wordplay probably does convey accurate information regarding the Roman settlement at Motza. See Fischer, Isaac and Roll, Roman Roads in Judaea II, 222. It is likely that the Jewish population in Motza was either extinguished or displaced prior to the establishment of the veterans’ settlement, and consequently the memory of the Second Temple-period village of Motza had begun to fade by the Talmudic period. This could explain why Motza had to be identified as Kalonya in rabbinic sources. ↩

- [13] If the two disciples were, indeed, returning home to Emmaus, this might provide further evidence in support of Robert Lindsey’s theory that at an early stage of his public career Jesus had itinerated throughout Judea. See Robert L. Lindsey, Jesus, Rabbi & Lord: A Lifetime’s Search for the Meaning of Jesus’ Words, 61-62; David N. Bivin, “Jesus in Judea.” Safrai, on the other hand, suggested that Emmaus was not the final destination of the disciples, but was a stop on their return route to the Galilee. See Shmuel Safrai, Pilgrimage at the Time of the Second Temple (Tel Aviv: Am Hassefer, 1965), 116 (in Hebrew). Safrai appears to have assumed that the Emmaus of Luke 24 was Emmaus-Nicopolis. ↩

- [14] Archaeological evidence for a Jewish presence in Motza at the end of the Second Temple period include a richly decorated Herodian-period private house south of the road near Motza and the use of Motza marl, a type of clay found at Motza, at a Herodian-period kilnworks at the outskirts of Jerusalem near and above the Emmaus Road. On the Herodian-period house, see Fischer, Isaac and Roll, Roman Roads in Judaea II, 226, 229. On the kilnworks, see Benny Arubas and Haim Goldfus, “The Kilnworks of the Tenth Legion Fretensis,” in The Roman and Byzantine Near East: Some Recent Archaeological Research (Journal of Roman Archaeology Supplementary Series 14; Ann Arbor: 1995), 95-107. ↩

- [15] The name Motza also appears on seal impressions on jar handles from the late sixth or early fifth century B.C.E. The reference is probably to the same location as that mentioned in Josh. 18:26. Note that the spelling on the jar handles (מצה and מוצה) agrees with the spelling in Joshua (with a final ה) instead of the spelling in the Mishnah (with the final א). On these seal impressions, see Nahman Avigad, “New Light on the MSH Seal Impressions,” Israel Exploration Journal 8 (1958): 113-119. ↩

- [16] Alexandrinus. Vaticanus renders הַמֹּצָה as Αμωκη (Amōkē). ↩

- [17] The “a” at the beginning of “Ammaous” evidently is Josephus’ representation of the Hebrew definite article. According to Fischer, Isaac and Roll (Roman Roads in Judea II, 223), “The name ‘Ammaus’ can only with some difficulty be understood as a derivative of ‘Hamoza,’ although this is not impossible. ↩

- [18] See Michael Zohary, Plants of the Bible: A Complete Handbook (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1982), 131. ↩

- [19] See Fischer, Isaac and Roll, Roman Roads in Judaea II, 95, 222, 229. ↩

- [20] See Fischer, Isaac and Roll, Roman Roads in Judaea II, 223. ↩

- [21] Fischer, Isaac and Roll (Roman Roads in Judaea II, 226) cite J. Press, Eretz-Israel, Topographical and Historical Encyclopedia, iii (1952, Heb.), 558-559, for the Roman bath, but have no further information to offer. ↩

- [22] See Y. H. Landu, “Unpublished Inscriptions From Israel: A Survey,” in Acta of the Fifth Epigraphic Congress of Greek and Latin Epigraphy Cambridge 1967 (Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1971), 387-390, esp. 389. ↩

- [23] Fischer, Isaac and Roll, Roman Roads in Judaea II, 228. ↩

- [24] Fischer, Isaac and Roll (Roman Roads of Judaea II, 223) estimated that it would take about an hour to walk thirty stadia, the distance Josephus measured between Jerusalem and the Emmaus that became a Roman colony. However Fischer, Isaac and Roll also note that Josephus’ measurement of thirty stadia from Jerusalem to Motza-Emmaus is only a rough estimate. They measure the distance as thirty-eight stadia, which agrees even better with the results of my walking experiment. ↩

- [25] See Wright, Greatness Grace & Glory, 197. ↩

- [26] The Israel Antiquities Authority’s report, entitled “Ma’ale Romaim, Road” was completed by Shachar Poni, Jerusalem’s city architect, and Jon Seligman, Jerusalem’ regional archaeologist, in the summer of 2002. The report can be viewed at the following web address: http://www.antiquities.org.il/images/archinfo//001-030/029.pdf, and is archived here. Translations of the IAA’s report quoted in this article are my own. ↩

- [27] For a more comprehensive description of this part of the Roman road, see Fischer, Isaac and Roll, Roman Roads of Judaea II, 95-97. ↩

- [28] See M. Avi-Yonah, “The Development of the Roman Road System in Palestine,” Israel Exploration Journal 1 (1950): 54-60; Israel Roll, “The Roman Road System in Judaea,” Jerusalem Cathedra 3 (1983): 136-161; Yoram Tsafrir, Leah Di Segni and Judith Green, Tabula Imperii Romani Iudaea Palestina: Eretz Israel in the Hellenistic, Roman and Byzantine Periods (Jerusalem: Israel Academy of Sciences and Humanities, 1994), 21; Fischer, Isaac and Roll, Roman Roads in Judaea II, 1. ↩

- [29] The milestone, which makes reference to the Emperor Vespasian, was found near present-day Afula in the Jezreel valley. On this milestone see, Benjamin Isaac and Israel Roll, “A Milestone of A.D. 69 From Judaea: The Elder Trajan and Vespasian,” Journal of Roman Studies 66 (1976): 15-19. On Roman milestones from the land of Israel in general, see Benjamin Isaac, “Milestones in Judaea from Vespasian to Constantine,” Palestine Exploration Quarterly 110 (1978): 47-60. ↩

Comments 4

David – thank you so much for writing this article and documenting the destruction. We can only hope that the authorities will recognize this treasure that is nearly lost. I’ve directed readers of my blog to this article with a couple of additional photos:

http://blog.bibleplaces.com/2017/03/the-destruction-of-road-to-emmaus.html

Thanks for a great article that sets the issue forth in a compelling fashion.

Thank you for this rich and memorable article. Well I remember bringing groups to this very road for you to guide back in the day. Let’s hope the planning authorities leave us something of this heritage gem!

An excellent article David! The pictures & videos are great blessings also.

After studying with Dwight for many years, each Pesach (Resurrection Day) & Shavuot, I wonder …

Motza is fairly easy to find particularly since the Temple Institute folks have begun the Willows from Motza tradition in their “practice ceremonies” of the water drawing, etc. at & from the pool of Siloam.

But Emmaus has remained more of a mystery to me over the years.

I for one really appreciate your (and others’) work on this. As always, Best Regards, Rob Wilson – CoM teaching elder.