When you enter into a marriage, you don’t do so expecting it to end. But sad as it is (“Even God sheds tears when anyone divorces his wife,” says the Babylonian Talmud, Sanhedrin 22a), it happens. And when it happens to a Jewish couple, the Bible requires the husband to provide his wife with a “bill of divorcement” (Deut. 24:1).

In my first historical novel, The Scroll, published by Menorah Books, the title and starring role were given to such a document—in this case a real bill of divorce, found in a cave in a place called Wadi Murabba‘at in the Judean Desert in the 1950s, but actually written at the desert fortress of Masada, where my novel begins. As a tour educator, I’ve taken thousands of people to Masada, where I tell the story of a band of rebels who held out against the Romans and eventually took their own lives. When I tell people that two women of Masada, and five children, survived according to the Jewish historian Josephus, they inevitably ask: What happened to them? With the help of that ancient divorce document, The Scroll offers an answer.

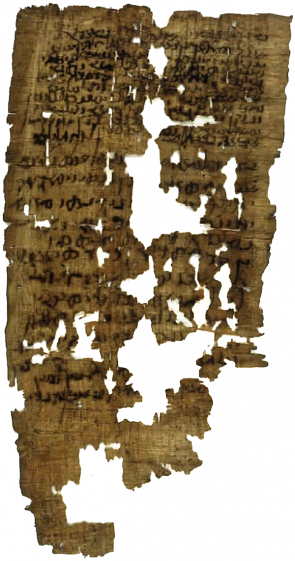

The divorce document from Wadi Murabba’at in the Judean Desert. Courtesy of the Israel Antiquities Authority.

What’s the Connection between Divorce and Love, David and Goliath?

I imagined that on that barren mountaintop, surrounded by enemies, the husband, whom the real document names as Joseph son of Naqsan, gave his wife, named Miriam daughter of Jonathan, a divorce of a very special kind—out of love. Joseph, I imagined, was about to go to war, and offered his wife what is known as a “conditional divorce” so she could go on with her life in case he didn’t return.

One Talmudic reference says this custom comes from the Bible, when the young shepherd David is told by his father to bring food to his brothers who are fighting the Philistines: “And to thy brethren shalt thou bring greetings, and take their pledge (1 Sam 17:17–18). The meaning of the Hebrew word for “their pledge”—arvutam—gets lost in some translations, where it boils down in some cases to Yishai simply asking David to find out how his other sons are faring. But in reality “their pledge” was much more. The Talmud says the meaning was: “things which are pledged between him and her,” in other words—their marriage vows. David, according to the sages, was to bring back word that his brothers were freeing their wives from their marriage vows if they did not return from battle but could not be confirmed dead.

The Valley of Elah, where David fought Goliath. Courtesy Wikimedia Commons.

Thus came the Talmudic dictum: “Everyone who goes out into the war of the House of David, writes for his wife a conditional divorce” (Ketubboth 9b). It’s understandable that the sages would look to that story, in which the Israelites quake in fear at the giant Goliath. Certainly, many never expected to survive the day, and thought about the wives and children they left behind. (Although hope springs eternal, it seems: Even as they were quaking, dismayed, terrified and fleeing, as the text tells us, they were telling each other that anyone who defeated the giant would earn himself a princess for a wife and financial benefits for his family.)

In Judaism, dissolution of a marriage under such circumstances is a hot issue to this day. The sanctity of the marriage vows dictates that a woman whose husband’s whereabouts are unknown for any reason is still “bound” to him unless definitive proof is shown that he won’t return. In fact, Prof. Dror Fixler of Bar-Ilan University (who in addition to being an Orthodox rabbi is also a physicist) tells us in an article he wrote on the subject[1] that the great medieval Jewish teacher Maimonides instructed husbands not to act as the “evil ones” who “bind” their wives to them forever even if their whereabouts in the fog of war might never be known.

But what happens if the husband eventually does turn up? Since this was a “divorce given out of love”—a phrase coined by the 20th-century Rabbi Yitzhak Yaakov Weiss in discussing this very subject—can they simply resume their lives together? Another medieval sage, Rabbi Moses Isserles had a solution: They would have to get married again. (And that has its own problems if the missing husband is a Cohen, a member of the priestly class, for example, who is forbidden to marry a divorcee!). I raised that complication in one dramatic twist in the plot of The Scroll, in a way that reverberates through its fictional generations.

Another proposal was that a rabbinic court hold on to the document, and give it to the wife in case the husband did not return after a specified period. That was suggested by Rabbi Isaac Herzog, chief Ashkenazi rabbi of Palestine and of Israel after Independence—whose life spanned two world wars and who certainly saw his share of such cases.

Indeed, the issue is still with us. Rabbi Fixler wrote that during the Second Lebanon War in 2006 a soldier asked him about obtaining such a document. Yet seemingly no such thing was to be found in the Israeli army’s archives. But, as Fixler reveals, something called IDF Manpower Directorate Form 821 is exactly that. Fixler concludes (as the Israeli army’s first chief rabbi, Shlomo Goren, did), that this type of document would not be widely accepted. Moreover it would be detrimental to morale. For those reasons it is apparently not made available to IDF soldiers.

What touches me most about the concept of “conditional divorce” is that this issue, with its deep Hebraic roots, like some equally controversial issues that I raise in The Scroll, is still with us. It shows us the living nature of our ancient biblical tradition and its millennia-long impact.

Cover of The Scroll, featuring the entrance to the cave where the divorce document was found, overlaid by a photo of the original document.

- [1] Dror Fixler, with an appendix by Amichai Redziner (2007). “The Giving of a Get Before going to War.” Tanhumin 27: 409–410. (Hebrew). ↩