How to cite this article: David Flusser, “Teaching with Authority: The Development of Jesus’ Portrayal as a Teacher within the Synoptic Tradition,” Jerusalem Perspective (2021) [https://www.jerusalemperspective.com/22992/].

Premium Members and Friends of JP must be signed in to view this content.

If you are not a Premium Member or Friend, please consider registering. Prices start at $5/month if paid annually, with other options for monthly and quarterly and more: Sign Up For Premium

This article is a translation of an excerpt from David Flusser’s German book on parables entitled Die rabbinischen Gleichnisse und der Gleichniserzähler Jesus.[19] It appears here in English for the first time.[20]

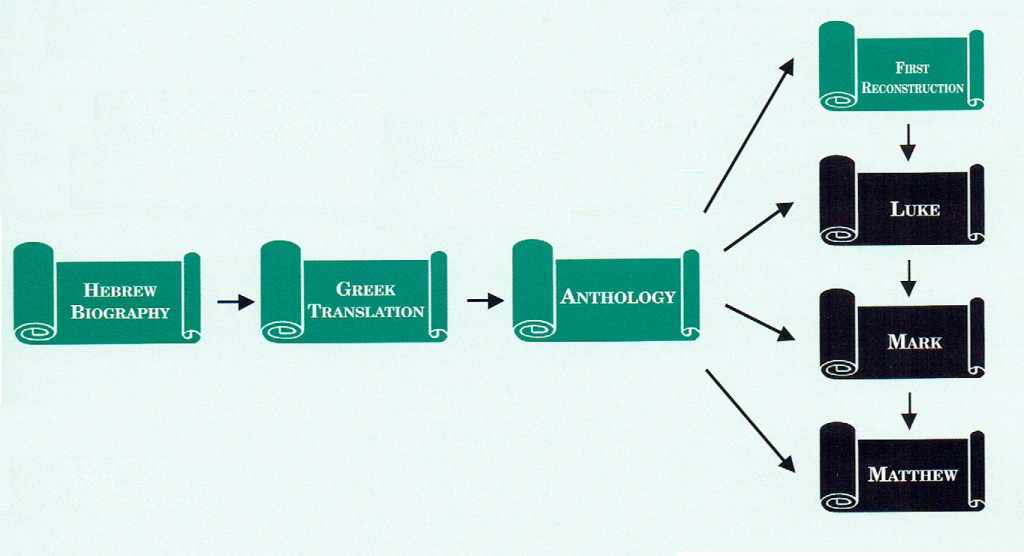

[209]Not long ago, while I was lecturing on the rabbinic background of the Sermon on the Mount, a New Testament professor objected, “How can you speak of Jesus’ rabbinic exegesis when we learn from Mark [In a redactional sentence!—DF] that Jesus taught ‘as one having authority, and not like the scribes’ (Mark 1:22)?” I replied to the theologian with all seriousness: “If Jesus was a person with authority, then he could also make rabbinic arguments based on his personal authority.” It was not until later that I [210] realized how this curious sentence in Mark’s version of the Capernaum Synagogue narrative (Mark 1:21-28) came into being. Without Lindsey’s synoptic theory[21] —according to which Luke is the earliest of the Synoptic Gospels, Mark is based primarily on Luke, and Matthew is based on two sources, Mark and one of the sources known to Luke—I would not have been able to understand the process that led to its formation.

Premium Members and Friends of JP must be signed in to view this content.

If you are not a Premium Member or Friend, please consider registering. Prices start at $5/month if paid annually, with other options for monthly and quarterly and more: Sign Up For Premium

- [1] Hugonis Grotii, Annotationes in Novum Testamentum: Denuo Emendatius Editae (ed. P. Hofstede de Groot; 9 vols.; Groningae: W. Zuidema, 1826-1834), 3:231. ↩

- [2] [229 n. 44] Luke 4:32 was written from the premise that Jesus appeared in Capernaum as a teacher for the first time. The editor therefore found it appropriate to speak of the audience’s amazement at Jesus’ teaching. The Gospel of Luke, on the other hand, already has Jesus appear (as a teacher) in the synagogue of Nazareth. Therefore, Luke 4:32 is a kind of doublet to Luke 4:22. The editor had already received the old report in Greek. Only in this way can we explain why he used the Greek word logos, which properly means “thing” in Luke 4:36, in the sense of “word” in Luke 4:32. But is “he was teaching them” in Luke 4:31 (cf. Mark 1:21) original, or could these words, too, have come from the pre-Lukan redactor? The earlier verse, Luke 4:15, which was composed in Greek and also speaks of Jesus’ teaching, gives the strong impression of being an editorial summary. At one point, Luke 4:31 certainly followed the editorial Luke 4:15. So it now seems to me entirely likely that the teaching of Jesus in the synagogue of Capernaum was inserted by the same pre-Lukan editor. If I am correct, then the original account did not speak at all of the teaching activity of Jesus during his first appearance in the synagogue of Capernaum, but only of Jesus’ first healing miracle! ↩

- [3] [229 n. 45] Except in our pericope (Luke 4:32; Mark 1:22, 27; Matt. 7:28), the word διδαχή does not appear with agreement from the synoptic evangelists anywhere in the Synoptic Gospels. I assume with Lindsey that Mark depends on Luke, and Matthew depends on Mark. In addition, the word occurs twice in Markan frame sentences (Mark 4:2; 12:38) and once in Matthew (Matt. 16:12), where the word is absent in Mark’s parallel. The Lukan parallel speaks of the “hypocrisy” of the Pharisees (Luke 12:1). Matthew 22:33 is an editorial conclusion that repeats what is written in Matt. 7:28. ↩

- [4] [229 n. 48] Usually one translates Mark 1:27 differently, because at this point the word “authority” is not taken too seriously and because one does not consider that the phrase “as a result of authority” is supposed to explain why the teaching of Jesus is new. The following division, “A new teaching! And with authority he commands the spirits...,” does not correspond to the Markan sentence, but rather to Luke 4:36. Mark 1:27 corresponds to Mark 1:22, which says: “He taught them as one who has authority.” See Vincent Taylor, The Gospel According to St. Mark (2d ed.; London: Macmillan, 1966), 176; Bruce M. Metzger, A Textual Commentary on the Greek New Testament (London, New York: United Bible Societies, 1975), 75. ↩

- [5] [229 n. 49] Mark 1:27 interprets τίς ὁ λόγος οὗτος (Luke 4:36) first in the sense of “What is this thing?” Immediately afterwards, however, Mark understands the Greek noun logos as “word” and so refers to a “new teaching.” He takes the noun διδαχή from Luke 4:32. ↩

- [6] Mark’s scribes have now become “their” scribes in Matthew. [229 n. 50] On this point and Matthew’s tendency to further the distance between Jews and Christians, see G. Strecker, Der Weg der Gerechtigkeit, 30. ↩

- [7] [229-230 n. 51] Looking back from Matt. 7:28-29, we see that Matthew interpreted the essence of the Sermon on the Mount in its light. It would be worthwhile to investigate how Matthew himself manipulated the words of the “historical” Jesus in the Sermon on the Mount through small but important changes, e.g., in Matt. 5:17f. his redaction created a tension towards the “Law.”

G. Strecker, “Die Antithesen,” ZNW 69 (1978): 36-72, judged differently regarding the tension thus created. He saw in Jesus the “speaker of the original antitheses.” Then he continued: “His teaching is fundamentally [sic!] opposed to the tradition of the ‘elders,’ it actually leads to the repeal of individual commandments of the Torah.” One should ask to what extent such a view does justice to Jesus and to what extent it is a modern metamorphosis that continues the centrifugal path of successive secondary redactors in the Gospels. In the light of my philological and critical examination of the term “authority” (exousia) in the pericope, it is instructive to see that when Strecker asks “about the motivation of Torah tightening and Torah criticism in the preaching of Jesus,” he concludes that “undoubtedly a heightened exousia-consciousness for Jesus must be assumed, without its being messianic.” ↩ - [8] [215] Luke, which, despite redactional activity, preserves the wording of the original source in Luke 4:36, knows nothing of the portrayal of Jesus’ teaching as a “new doctrine.” Moreover, when Luke recounts Paul’s visit to Athens (Acts 17:19-21), the term “new doctrine” conveys a distinctly negative meaning. Paul is asked on the Areopagus: “‘Can we know what this new doctrine is that you are teaching? For you bring strange things to ears. So we want to know what they may be.’ All Athenians and the strangers present there have no time but to say or hear something new.” Thus Luke criticized the Athenians, who, eager for something new, wanted to learn about Paul’s “new teaching.” ([230 n. 56] See Hans Conzelmann, Die Apostelgeschichte, 97.) Luke did not want the Christian message to be classified as a “new doctrine.” But let us return to Mark! ↩

- [9] [230 n. 52] E. Klostermann has drawn attention to this parallel in Das Markusevangelium, 17f. It is the apocryphal fragment from Papyrus Oxyrhynchus No. 1224. Klostermann himself published it in Apokrypha II, Evangelien (Kleine Texte 8), 26. I follow his edition. ↩

- [10] [230 n. 53] See David Flusser, “An Early Jewish-Christian Document in the Tiburtine Sibyl,” in idem, Judaism and the Origins of Christianity (Jerusalem: Magnes, 1988), 359-389, esp. 379-384. ↩

- [11] For more on Flusser’s identification of the author of Mark, see David Flusser, “Character Profile: Who Was John Mark?”—JP. ↩

- [12] [230 n. 54] See David Flusser, “The Dead Sea Sect and Pre-Pauline Christianity,” in Scripta Hierosolymitana IV: Aspects of the Dead Sea Scrolls (1958): 215-266, repr. in idem, Judaism and the Origins of Christianity, 23-74. ↩

- [13] [230 n. 55] See Flusser (above, n. 54), 236-242. That a covenant or a new covenant was made through Jesus is an idea that is alien to Jesus and the sources of the Gospels. The covenant was not mentioned in the original wording of the words of Jesus at the Last Supper (Luke 22 according to the Codex Bezae). This is different with Mark (Mark 14:25), on whom Matthew depends (Matt. 26:28). In the context of the Lord’s Supper Paul spoke of the “new covenant” (1 Cor. 11:25). See also David Flusser, “The Last Supper and the Essenes,” in idem, Judaism and the Origins of Christianity, 202-206. ↩

- [14] The discussion of the Patch and Wineskin similes is beyond the scope of the present excerpt from Flusser’s German book on parables—JP. ↩

- [15] [230 n. 57] In Melito’s Easter homily. See O. Perler (ed.), Meliton de Sardes, Sur la Päque. Sources Chretiennes, 123. German translation by J. Blank. On page 52, Blank cited the quotation from Irenaeus. ↩

- [16] Translation adapted from The Ante-Nicene Fathers (10 vols.; ed. Alexander Roberts, James Donaldson, Allan Menzies; repr. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1980-1986), 1:511—JP. ↩

- [17] See Yigael Yadin, The Finds from the Bar Kochba Period in the Cave of Letters (Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society, 1963), 182-187. ↩

- [18] Yigael Yadin, Tefillin from Qumran (X Q Phyl 1-4) (Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society and the Shrine of the Book, 1969), 9. ↩

- [19] David Flusser, Die rabbinischen Gleichnisse und der Gleichniserzähler Jesus (Bern: Peter Lang, 1981). In this article page numbers from the original version are marked in blue within square brackets (e.g., [209])—JP. ↩

- [20] For an overview and evaluation of Flusser’s German book on parables, see Peter J. Tomson, “Review: David Flusser’s Die rabbinischen Gleichnisse und der Gleichniserzähler Jesus (1981),” at WholeStones.org—JP. ↩

- [21] For an introduction to Lindsey’s hypothesis, see Robert L. Lindsey, “Unlocking the Synoptic Problem: Four Keys for Better Understanding Jesus”—JP. ↩

![David Flusser [1917-2000]](https://www.jerusalemperspective.com/wp-content/uploads/userphoto/21.jpg)

Comments 3

Pingback: Corrections and Emendations to Flusser’s Judaism of the Second Temple Period | JerusalemPerspective.com Online

I’ve been puzzled by Flusser’s odd use of the term “flashback” in this article, but I just came across a parallel usage in Flusser’s introduction to Judaism and the Origins of Christianity (xxv n. 35): “Not only is the wording in Mark 3:6 dependent upon Luke 6:9 but it is also a clear flashback to Luke 22:2 (private conversation with R. L. Lindsey).” What Flusser calls a “flashback” is really pulling something from a later part of the narrative back into an earlier part of the story. Is “flashback” Flusser’s term for the phenomenon, or was it coined by Lindsey?

By the way, I’m pretty sure that Flusser’s reference to Luke 6:9 in the quotation from JOC above is a mistake. The correct reference is Luke 6:11.