How to cite this article: Robert L. Lindsey, “The Kingdom of God: God’s Power Among Believers,” Jerusalem Perspective 24 (1990): 6-8 [https://www.jerusalemperspective.com/2445/].

The terms “Kingdom of God” and “Kingdom of Heaven” are not found in the Hebrew Scriptures, but apparently were developed later by the Pharisees. In the Second Temple period the commandment against taking the LORD’s name in vain was so strictly interpreted that people used euphemisms to avoid unintentionally misusing his name. Jesus would have followed the same practice—to do otherwise would have shocked his listeners.[1]

The “Kingdom of Heaven” is the מַלְכוּת שָׁמַיִם (malchūt shāmayim) spoken of by the sages, and “Heaven” here is simply a synonym for “God”—much as we use “Heaven” today, for instance, when we exclaim, “Thank Heaven!” The terms “Kingdom of God” and “Kingdom of Heaven,” therefore, are interchangeable. Jesus did not speak of two divine kingdoms, but only one.

What Is This Kingdom?

An important key to understanding Jesus’ use of “Kingdom of God” is how the sages used it. With the sages it was a spiritual term meaning the rule of God over a person who keeps or begins to keep the written and oral commandments. This is illustrated by a statement of Rabbi Yehoshua ben Korhah:

Why is “Hear, O Israel” [Deut. 6:4-9] recited before “If, then, you obey the commandments” [Deut. 11:13-21] in the daily prayers? To indicate that one should accept first the kingdom of Heaven, and only afterwards the yoke of the commandments. (Mishnah, Berachot 2:2)

The sages felt that when a person confessed, “The LORD is our God, the LORD alone,” indicating his or her intention to keep the Torah, that person came under God’s rule and authority, and thus came into the Kingdom of God. Having accepted God’s authority over him or her, the person was able to begin keeping the commandments.

A shepherd removes a temporary stone barrier from a sheepfold to let his flock out to graze. Illustrator: Phil Crossman.

Jesus spoke of the Kingdom with the same understanding in Matthew 7:21: “Not everyone who says ‘Lord, Lord’ to me will come into the Kingdom of Heaven, but he who does the will of my Father who is in heaven.” The emphasis is on the importance of keeping God’s commandments, but Jesus’ use of “Kingdom of Heaven” is the same as Yehoshua ben Korhah’s in the passage above. Both of these sages spoke of God’s kingdom being rooted in the confession of his authority and the doing of his will.

According to Jesus’ definition, this kingdom is limited: only those who follow him are included. The Kingdom should not be confused with God’s providential rule: “Heaven is my throne and the earth is my footstool” (Isa. 66:1); in this general sense, the LORD is king of the universe. Neither should it be viewed as an earthly political movement, out to rule by cross and sword or to ordain Christian leaders to govern a largely unconverted world.

Understanding what the Kingdom is should clear up confusion about the period of time to which it refers. The Kingdom of God appears whenever individuals take upon themselves the rule of God. When Matthew 7:21 is translated back into Hebrew, one recognizes its proverbial form in which there is no real future tense. The saying should be understood: “Not everyone who says ‘Lord, Lord’ to me comes into the Kingdom of Heaven….” The second part of the verse likewise reflects the idea of present time: “but he who is doing the will of my Father….”

Matthew 6:10 makes the same point: “Your Kingdom come, your will be done in heaven and on earth.” The phrases are synonymous: people come into the kingdom when they accept God’s authority and begin to do his will.

Jesus’ Movement

The Kingdom of God is the movement led by Jesus. He primarily used “Kingdom of God” to describe the body of his followers among whom God was present in power. The following examples characterize the Kingdom as an expanding movement made up of Jesus’ followers.

In the story of the Beelzebul controversy (Luke 11:14-26), people in the crowd accuse Jesus of casting out evil spirits with the aid of Satan. Jesus points out that it would not be sensible to think of the demons as being divided against each other under Satan’s rule. Jesus casts out demons through God’s power and, thus, demonstrates that the Kingdom of God has manifested itself to those who have seen what has happened: “If I cast out demons by the finger of God, then the Kingdom of God has come upon you” (vs. 20).[2]

When Jesus cast out an evil spirit by God’s power, God took charge; he was in authority over Satan at that moment. The people who saw the miracle had not necessarily submitted to God’s rule, but they saw God at work just the same.

In the story of the rich man in Matthew 19, Mark 10 and Luke 18, Jesus challenges the man to sell all he has, give it to the poor and “come, follow me.” The man turns away and Jesus says, “How difficult it is for a rich man to come into the Kingdom of Heaven!” To join the movement Jesus is leading, one submits to his authority and thereby comes into the Kingdom of God.

When Peter asked what it meant that he and the other disciples had “left all” and followed Jesus, Jesus replied, “There is no one who has left home…for the sake of the Kingdom of God who will not receive more in this life—and in the world to come, eternal life.” Being a part of the Kingdom of God was literally to follow Jesus, to take up one’s cross and follow him, to join his divine movement. It was to be a part of others who together would be blessed in the Kingdom of God in its earthly manifestation and, in the world beyond, would inherit eternal life.

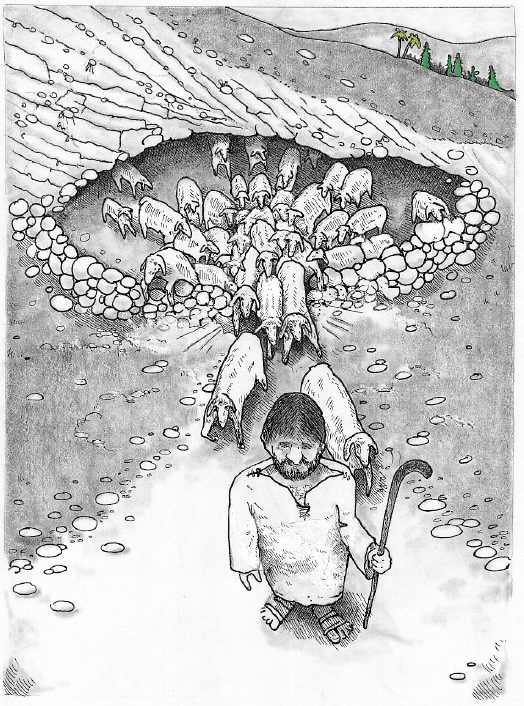

“The breaker will go up before them; they will burst through the gate and go out.” (Mic. 2:13) Illustrator: Phil Crossman.

In the context of the parable of the two sons, Jesus says: “The tax collectors and prostitutes are coming into the Kingdom of God ahead of you, for John has come in the way of righteousness and you have not believed him, but the tax collectors and prostitutes have believed him” (Matt. 21:31-32). Jesus was speaking of individuals, tax collectors and prostitutes, becoming part of a group—the Kingdom of God.

Jesus honored John the Baptist as the last great prophet of old: “Among those born of women, no one has lived who is greater than John the Baptist” (Matt. 11:11-14). However, Jesus added that “the smallest in the Kingdom of Heaven is greater than John.” It was possible to speak of the greatest or smallest in the Kingdom, because it is a movement made up of individuals.

In Matthew 11:12 Jesus says: “From the days of John the Baptist until now the Kingdom of Heaven has been breaking forth….” This passage is an oblique reference to Micah 2:13, where the Messiah “breaks down [the makeshift stone corral wall to let out the sheep in the morning]. They pass through the gate with their king before them and the LORD at their head….” Jesus’ reference to the Kingdom “breaking forth” characterized the movement as a large and expanding group, of which he was the “breaker” or shepherd, the king and even the LORD.

The Kingdom Is Near

Some passages that seem to prove that Jesus referred to a future earthly kingdom should be considered in their Hebraic context. In Luke 10:8-9 we read that Jesus sent his disciples out to preach and teach, and instructed them that when they entered a village or town, they were to eat and drink in the homes that accepted them. Upon healing the sick they were to say, “The Kingdom of God has come near to you.”

In the Greek text the phrase “has come near you” appears to be a reference to time. However, translated into Hebrew it becomes קָרְבָה אֲלֵיכֶם (qārvāh ’alēchem), and in such a context it should be understood not in the sense of time but of space. This is an idiom that connotes physical intimacy and is even used seven times in the Hebrew Scriptures as a euphemism for sexual intercourse (Gen. 20:4; Lev. 18:6, 14; 20:16; Deut. 22:14; Isa. 8:3; Ezek. 18:6).

God’s rule is demonstrated when a miracle of healing occurs as much as when a demon is cast out. When the disciples exclaimed, “The Kingdom of God has come near,” they were interpreting the healing as the immediacy of God’s presence in power. In effect, the Kingdom was not near but already present. Their Hebrew declaration meant, “God has taken charge here.”

C. H. Dodd, who wrote the influential The Parables of the Kingdom in 1935, argued for this interpretation of the passage. Had he believed that the Gospel texts strongly reflect a Hebrew original, he might have achieved more success with his theology of “realized eschatology.” The failure of many scholars to understand Jesus’ use of the expression “Kingdom of God” or “Kingdom of Heaven” lies largely in their failure to take seriously the highly Hebraic character of a great deal of the Gospels.

Much of the material in the Synoptic Gospels seems to be translated from Hebrew. We must attempt to discover the underlying Hebrew original, comparing rabbinic usage when possible. In the case of “Kingdom of God,” we find that the overwhelming majority of Gospel texts uses this term to describe an expanding community of believers led by Jesus, through whom God manifests his power and blessing.

Sidebar by Shmuel SafraiThe expression מַלְכוּת שָׁמַיִם (malchūt shāmayim, “Kingdom of Heaven”) appears only in rabbinic literature and the Gospels. It does not appear in the Scriptures, the literature created by the Essenes (the Dead Sea Scrolls), or in the Apocrypha and Pseudepigrapha. This is important and often overlooked by scholars. The world of Jesus is a world in common with the sages, not with the Essenes or the apocalyptists. In addition to malchut shamayim, there are many other terms that are unique to Jesus and the sages, such as מָשָׁל (māshāl, “parable”)—in the Bible mashal refers to a proverb and not to the entire story-parables told by Jesus and the sages of his day—and תְּשׁוּבָה (teshūvāh, “repentance”). The word teshuvah is not found, for example, in the Scriptures, in Philo or in the Dead Sea Scrolls. The sages’ view was that to ensure that the observance of the mitsvot (commandments) would not be mechanical, one should first commit oneself to the Kingdom of Heaven before beginning to observe God’s commandments. This was the view of Yehoshua ben Korhah (Mishnah, Berachot 2:2). This committing oneself to the Kingdom of Heaven is formalized by one’s confession of the Shema, the declaration that there is but one God, but its practical expression is in the observance of the commandments. In effect, the moment a person did a good deed—that is, the will of God—at that moment he came into the Kingdom of Heaven. There is a final redemption or completion of the Kingdom, but both Jesus and the sages generally viewed the Kingdom in a more practical, everyday way: doing the will of God. They would have viewed the final redemption in a fashion similar to the well-known rabbinic saying found in the Mishnah: “It is not your part to finish the task, yet neither are you free to desist from it” (Mishnah, Avot 2:16). There is a story in rabbinic literature that helps illustrate the first-century Jewish understanding of the Kingdom of Heaven and also supports Dr. Lindsey’s position:

The ruling that a bridegroom is exempt from reciting the Shema on the first night of his marriage is not found in the Written Torah, but it is part of the Oral Torah. One was permitted, as it were, to put aside the Kingdom temporarily. Gamaliel, however, refused to forget about the Kingdom even for a few moments. |

- [1] See David Bivin, “Jesus and the Oral Torah: The Unutterable Name of God,” JerPers 5 [Feb. 1988]: 1-2). ↩

- [2] See R. Steven Notley, “By the Finger of God,” JerPers 21 [Jul./Aug. 1989]: 7). ↩

![Robert L. Lindsey [1917-1995]](https://www.jerusalemperspective.com/wp-content/uploads/userphoto/28.jpg)

Comments 2

I find it ironic that the use of “Hebraic background” is cited to prove the point, but the Hebrew Bible’s teaching about the kingdom is largely ignored. There are examples everywhere, but an easy and clear one is Daniel 2:44: “In the time of those kings, the God of heaven will set up a kingdom that will never be destroyed.” Surely this is the kingdom of God that Jesus’ audience was expecting, and it replaces the kingdoms of men (Babylon, Greece, etc.) and is thus not a movement of disciples.

An important resource that is devastating to Dodd’s theory is Clayton Sullivan, Rethinking Realized Eschatology (Mercer University Press, 1988). I recommend it.

I don’t believe the writer of this article is subscribing to “realized eschatology”, it’s suggesting that had Dodd realized that the ‘kingdom’ message wasn’t just about an end time reality, he may have succeeded further with his theory.

Certainly in the ultimate sense, God will rule in person over all the nations; however

the technical term ‘kingdom of god’ or ‘kingdom of heaven’ isn’t found in the Old Testament. These phrases appear in the New Testament and rabbinic literature (See Aspects of Rabbinic Theology by Solomon Schechter, 65). The kingdom of God is a hermeneutical development.

That said, the foundation for these phrases certainly is. Exodus 15:18 captures this when Moses sings, “The LORD reigns for ever and ever.” God’s reign is in the present tense. Jesus makes reference to Exodus 8:19 when he says, “But if I cast out demons by the finger of God, then the kingdom has come upon you.” in Luke 11:20. God’s Rule or Kingdom is a present reality for those who make him their king. It’s God’s redemptive movement breaking into the realm of men. See Brad Young’s book Jesus the Jewish Theologian, 49 and James Charlesworth’s book The Historical Jesus – An Essential Guide, 97).