Revised: 11 January 2023

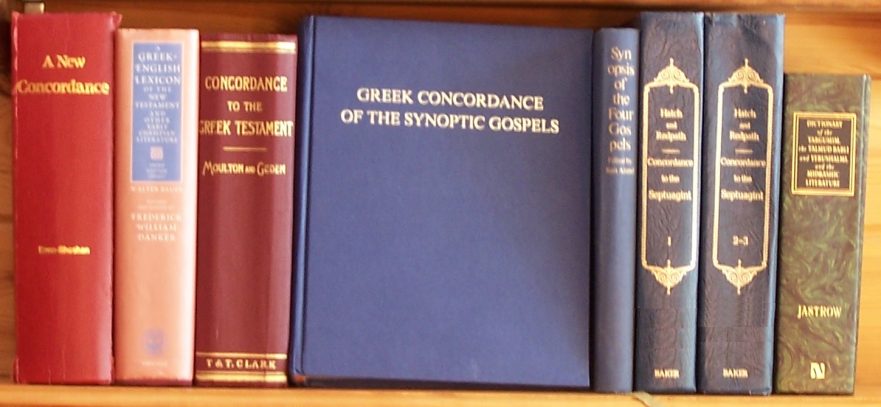

A good teacher not only conveys knowledge, but gives his students the tools by which they may continue learning. With the publication of the third and final volume of A Comparative Greek Concordance of the Synoptic Gospels, Dr. Robert Lindsey has given to the scholars who have been following his work, as well as to future scholarship, a necessary tool for the study of the Synoptic Gospels.

The concordance is laid out in such a way that the vitally important data that Lindsey long ago saw embedded in the literary strata will be more easily seen by others. The verse-by-verse comparison offers building blocks for grasping the literary relationship of the Synoptic Gospels, and more clearly understanding the life and teachings of Jesus.

Parallel References

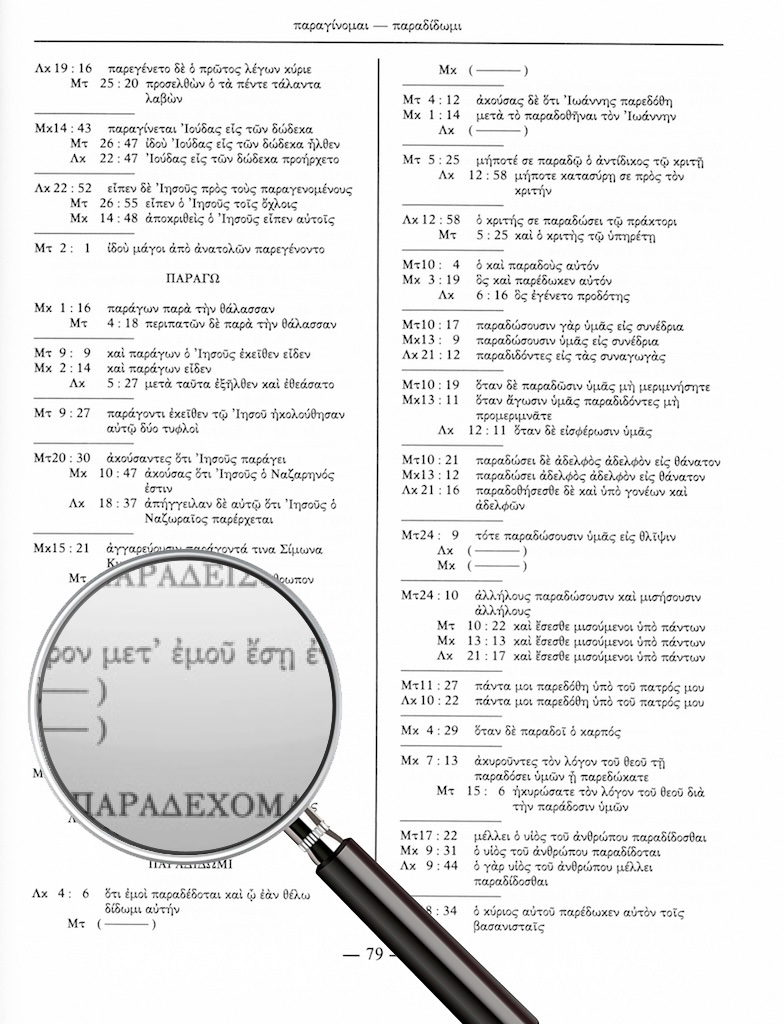

Anyone who has studied the Synoptic Gospels will quickly realize the valuable contribution this new concordance makes to comparative Gospel research. Most New Testament concordances list entries in order of their appearance, which makes it quite difficult to determine whether a word in the Synoptic Gospels is used in parallel pericopae, omitted or substituted by another word. With Lindsey’s concordance, the student can immediately see the answers to these questions.

Let us take as an example the noun εὐαγγέλιον (evangelion, gospel). An ordinary Greek New Testament concordance would list the four occurrences of evangelion in Matthew before the word’s first occurrence in Mark, but Lindsey’s synoptic concordance lists the first occurrence of evangelion as Mark 1:1 since that is the first occurrence of the word in a synopsis. The concordance indicates by indentation and solid line that there is no parallel to evangelion in this pericope, however there is a general parallel (paragraph or pericope in length) in both Matthew and Luke (an English translation is provided for the convenience of our readers):

Μκ 1:1 Αρχὴ τοῦ εὐαγγελίου Ἰησοῦ Χριστοῦ

Μτ (———)

Λκ (———)

Mk 1:1 The beginning of the Gospel of Jesus Christ

Mt (———)

Lk (———)

Another reference to evangelion, in Matthew 26:13, is also absent in the Lukan parallel but is found in the Markan parallel. This reference and its parallels are presented in the Lindsey concordance in the following manner:

Μτ 26:13 ὅπου ἐὰν κηρυχθῇ τὸ εὐαγγέλιον τοῦτο

Μκ 14:9 ὅπου ἐὰν κηρυχθῇ τὸ εὐαγγέλιον

Λκ (———)

Mt 26:13 wherever this gospel is preached

Mk 14:9 wherever the gospel is preached

Lk (———)

Because both Matthew and Mark employ the word evangelion, their references appear in the concordance without indentation. Luke has a general parallel to the Matthean-Markan context in his very similar story (Luke 7:36-50), but without the word evangelion, and so the Lukan reference is indented and shown with a solid line.

Another of the eleven synoptic contexts in which evangelion appears is found in Matthew 4:23:

Μτ 4:23 διδάσκων ἐν ταῖς συναγωγαῖς αὐτῶν καὶ κηρύσσων τὸ εὐαγγέλιον τῆς βασιλείας

Μκ 1:39 κηρύσσων εἰς τὰς συναγωγὰς αὐτῶν εἰς ὅλην

Λκ 4:44 ἦν κηρύσσων εἰς τὰς συναγωγὰς

Mt 4:23 teaching in their synagogues and preaching the gospel of the kingdom

Mk 1:39 preaching in their synagogues in all

Lk 4:44 he was preaching in the synagogues

Here indentation of the Markan and Lukan references indicates that these are phrase- or sentence-length parallels to Matthew, but that Mark and Luke lack the word evangelion. As with other entries, the reader here is able immediately to see whether one of the synoptists has replaced a word with a substitute, and whether there is a pattern of substitution.

Markan Pickups

One of Lindsey’s purposes in producing the concordance was to help others see the phenomenon he calls “Markan pickups.” Lindsey discovered that Mark replaces words and phrases in Lukan parallels with synonyms that are borrowed from other contexts in Luke. For instance, Mark picks up στέγη (stege, roof) from Luke 7:6 in the story of the centurion’s servant and uses it as a replacement in Mark 2:4 for Luke’s δῶμα (doma, roof) in the story of the healing of the paralytic (Luke 5:17-26).

Although Mark’s method may seem inane to the western mind, for students of Jewish literature Mark’s style is very familiar. His Gospel resembles the work of contemporary Jewish commentaries (midrashim and targumim). Lindsey’s concordance helps a student to observe this kind of replacement more easily, and thus to see that Mark is using Luke and not vice versa. In an ordinary concordance of the Greek New Testament, this kind of synonymic replacement is difficult to trace.

The Problem of Agreements

Another important contribution that should not be overlooked is Lindsey’s introduction to the concordance. Most Jerusalem Perspective Online readers are already aware of Lindsey’s pioneering work in identifying linguistic traces of a pre-synoptic Hebrew life of Jesus. The process and result of his discovery were published in A Hebrew Translation of the Gospel of Mark (1973) and elsewhere in scholarly and popular formats, yet in no place is his insight into the synoptic relationship presented in such a clear and convincing manner as in his introduction to this concordance. (For an emended and updated version of the introduction, see Robert L. Lindsey, “Measuring the Disparity Between Matthew, Mark and Luke.”)

Lindsey outlines the inability of the theory of Markan priority, held by most scholars, to explain the data found in the Synoptic Gospels. For example, Lindsey cites Matthew and Luke’s mutual inclusion of “lengthy additions” to Mark’s version of the Temptation of Jesus (Mark 1:12, 13; Matt. 4:1-11; Luke 4:1-13), as well as to Mark’s account of the Baptist’s preaching (Mark 1:7-8; Matt. 3:7-10; Luke 3:7-9). If, as most scholars think, Matthew and Luke are unaware of each other’s composition, then these common “additions” suggest that they have a source other than Mark at these points.

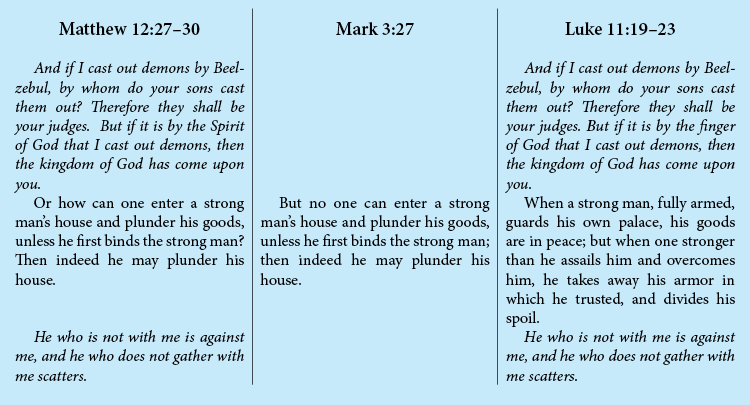

An even more poignant example of Matthean-Lukan “additions” opposite Mark is found in the Beelzebul controversy.

Lindsey points out another difficulty for Markan priorists: in Double Tradition, Matthew and Luke are able faithfully to reproduce material from their common non-Markan “sayings source” (which scholars have termed “Q”), but are unable to do so in Triple Tradition. Notice, for instance, the high degree of verbal identity between Matthew and Luke in the passage above when Mark is not present, but the low degree of identity when he is. Matthew consistently follows Mark more closely in Triple Tradition, while Luke demonstrates a distinct independence.

These facts, together with Mark’s influence on the ordering of the synoptic material, led Lindsey to conclude that Mark held the middle position in the synoptic tradition (see Lindsey’s “An Introduction to Synoptic Studies,” Subheading: “The Markan Cross-Factor.”)

Minor Agreements

The challenge presented to Markan priority by the Matthean-Lukan agreements against Mark has been recognized since the time of B. H. Streeter (The Four Gospels, 1924). Streeter reasoned that the “lengthy additions” were overlaps of Mark and Q material, and that where Matthew and Luke independently agree against Mark in making these additions, they are drawing from Q.

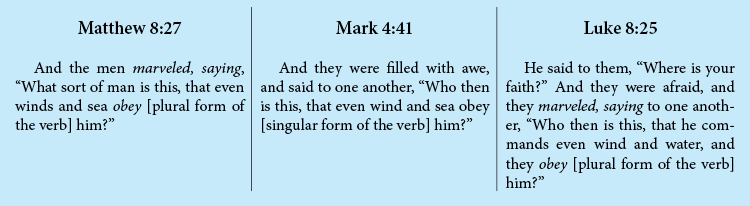

If the agreements were limited to the eight pericopae identified by Streeter, then the difficulty for the proponents of Markan priority would be minimal. However, many Matthean-Lukan agreements against Mark occur which involve only slight details—the addition or omission of a word, the replacement of a word with a synonym, a change of word order, use of the singular rather than plural form of a noun. In his introduction Lindsey gives examples of such agreements.

Agreements of this sort were considered by Streeter, Bultmann and others to be the result of pure chance and scribal harmonization. In an attempt to minimize their importance, they called them “minor agreements,” and one receives the feeling from Streeter and Bultmann’s evaluation that these agreements are rare accidents in the literary development of the Synoptic Gospels. However, Frans Neirynck has cataloged 1,005 instances of “minor agreements” involving over 4,000 words (The Minor Agreements of Matthew and Luke Against Mark, 1974, pp. 55-195). The sheer number of the “minor agreements” challenges the credibility of Streeter and Bultmann’s explanation.

The implications of “minor agreements” are significant for those embracing Markan priority and the “Two-source” hypothesis. These two pillars of modern synoptic criticism rest upon the assumption that Matthew and Luke independently used Mark and Q. If, however, Matthew knew Luke’s Gospel, or a source on which Luke is based, as well as Mark, then the need for Q to explain non-Markan material would be eliminated. “Further, the priority of Mark itself is threatened, since it is no longer needed as the narrative source which Matthew and Luke combined with Q to produce their Gospels” (E. P. Sanders, “The Overlaps of Mark and Q and the Synoptic Problem,” New Testament Studies 19 [1973]: 454).

Sanders has demonstrated that not all of what Streeter identified as Markan overlaps conforms to Streeter’s own limiting criteria. Conversely, other Markan overlaps are ignored by Streeter. To follow Streeter’s method of identifying Matthean-Lukan agreements as Markan-Q overlaps will produce surprising results: “If Q were made responsible for all these agreements in addition to the traditional Q material, it would be very much like Matthew. To expand the theory of Markan-Q overlaps much beyond Streeter’s bounds is simply to deny the two-source hypothesis” (Sanders, “Overlaps,” 455).

The extent of Q in Streeter’s theory is widened beyond the simple “sayings source” to include narrative material. We may rightly ask with Sanders what compels us to limit Markan-Q overlaps to those instances where Matthew and Luke are in agreement. Streeter explains the differences between Mark and Luke concerning “The Rejection in Nazareth” as a result of an overlap between Mark and L (Luke’s special source). The effect is that Q tends to look more like a “Proto-Gospel” than a simple non-Markan “sayings source.” Such a source removes the necessity for Q and Mark as the primary sources for Matthew and Luke.

Conclusions

Any project of this size must necessarily have its limitations. Lindsey has chosen as his Greek text for the concordance the ninth edition of Albert Huck’s Synopsis of the First Three Gospels, now out of print. Students may find it a bit disconcerting that texts from Kurt Aland’s Synopsis of the Four Gospels (13th edition, 1985) on rare occasions are not to be found in Lindsey’s concordance, however at points Huck has selected a better reading than Aland.

The most stark contrast is Huck’s choice of the reading: “You are my son, today I have begotten you” (Luke 3:23). Aland has chosen the reading of manuscripts that have been harmonized with Mark and Matthew: “You are my beloved son, with you I am well pleased.” The second reading no doubt is a result of the Church’s struggle against adoptionist tendencies, eliminating any suggestion that it was only at his baptism that Jesus was “begotten” or adopted as God’s son. The ancient Church’s theological position notwithstanding, the text presented in Huck’s synopsis, displaying a clear hint at the messianic Psalms 2:7, is to be preferred.

It is hoped that any future editions of the concordance will include significant textual variants. Of particular importance are some readings found in Codex Bezae. This ancient codex often provides the key to unlocking linguistic and historical problems. Note the omission in Codex Bezae of ἁμαρτωλῶν (hamartōlōn, sinners), in Luke 5:30, where Jesus and his disciples are accused of eating with tax collectors. The Codex Bezae reading agrees with the setting already depicted in verse 29. The inclusion of “sinners” in some manuscripts results from the tendency to harmonize Gospel texts.

A more important reading is Codex Bezae’s “shorter version” of Luke 22:19-20: “And he took bread, and when he had given thanks he broke it and gave it to them, saying, ‘This is my body.'” Many scholars agree that Codex Bezae preserves the better reading here, and that other manuscripts attempt to harmonize Luke with Mark and Matthew by including an extended portion from 1 Corinthians 11.

A Comparative Greek Concordance of the Synoptic Gospels makes a significant contribution to Gospel scholarship. It is laid out in a clear and easily accessible manner, and any student of the Synoptic Gospels will find it a valuable contribution to his or her library.

Paid Content

Premium Members and Friends of JP must be logged in to access this content: Login

If you do not have a paid subscription, please consider registering as a Premium Member starting at $10/month (paid monthly) or only $5/month (paid annually): Register

One Time Purchase Rather Than Membership

Rather than purchasing a membership subscription, you may purchase access to this single page for $1.99 USD. To purchase access we strongly encourage users to first register for a free account with JP (Register), which will make the process of accessing your purchase much simpler. Once you have registered you may login and purchase access to this page at this link: