Sometime in the middle of the second century A.D., Papias wrote, “Matthew recorded the sayings [of Jesus] in Hebrew, and everyone translated them as he was able.” Papias’ statement was quoted by another bishop named Eusebius, who lived between 263-339 A.D. It is in Eusebius’ Ecclesiastical History[1] that Papias’ testimony has survived.

Papias provides us with two very important bits of information. The first is that the disciple Matthew recorded the teachings of Jesus in the “Hebrew language.” Although some would argue that Papias’ Ἑβραΐδι διαλέκτῳ (Hebraidi dialekto) really means Aramaic, this is probably not the case, as Jehoshua Grintz has demonstrated.[2]

The second important bit of information is that other individuals reworked this original Hebrew composition. The question is, in what manner? The Greek verb ἡρμήνευσε (hermeneuse), rendered above as “translated,” can mean “to explain, interpret, or translate.” The ambiguity is generated more by the English language than by the Greek. Apparently, the ancients did not make the fine and often arbitrary distinction we do between translation and commentary. To put it another way, the ancients had a different approach to translating sacred texts than that which is taken by modern scholars. They tended to be less rigid. If there was an unclear verse, it was not uncommon for an ancient translator to help clarify it. If a strong tradition surrounded a certain passage, it was not unusual for elements of that tradition to creep into the text.

A good example of an unclear verse that has been clarified in the process of translation is Genesis 4:8, “And Cain told Abel his brother. And it came about when they were in the field, that Cain rose up against his brother and killed him” (New American Standard Bible).

Obviously some important details, such as what Cain told Abel, are missing. These were supplied by the Septuagint translator: “And Cain told Abel his brother, ‘Let us go out into the field….'” It is possible that the translator of the Septuagint had a manuscript in front of him that included the clause, “Let us go out into the field,” but it is just as likely that he felt the text was incomplete and supplied the information.

A more radical example appears in the targumim, where such liberties are more common and pronounced. For example, Targum Neofiti’s rendering of Genesis 22:1 is:

Now it came about after these things that the LORD tested Abraham with the tenth test. He said to him, “Abraham!” And Abraham answered in the tongue of the House of the Holy One. And Abraham said to him [the LORD], “Here I am.”

In this one verse two new elements have been introduced: God is testing Abraham for the tenth time; Abraham (the Aramean) answered in Hebrew, the Holy Language. The first is an early and well-known Jewish tradition about this passage. The second represents an issue of great concern to the sages at the time this Targum was composed—the displacement of Hebrew by Aramaic.[3] Both accretions became part of an Aramaic translation of Scripture.

Returning to Papias’ claim, we now ask: What were those individuals who were translating “…as they were able” doing with Matthew’s composition? No definite answer to this question is available. From the above examples, especially that of the targumim, it is safe to postulate that all of them were not producing translations akin to the King James Version. Some translators treated Matthew’s Hebrew composition conservatively, but others may not have. One can imagine that from the very start a proliferation of materials about Jesus’ life occurred.

At this point assistance is available from another quarter. In the prologue to his Gospel, Luke writes:

Inasmuch as many have undertaken to compile an account of the things accomplished among us…it seemed fitting for me as well, having investigated everything carefully from the beginning, to write it out for you in consecutive order, most excellent Theophilus; so that you might know the exact truth about the things you have been taught.” (New American Standard Bible)

Luke is providing another clue to the transmission process of the Gospel sources. Like Papias, he writes that a number of individuals had attempted to compile an account of Jesus’ life. He, however, says something more.

Luke’s use of καθεξῆς (kathexes, consecutive order) implies that confusion had arisen, not just from a proliferation of sources, but from the loss of the story’s chronological order. Though this sounds very strange, it is not without precedent in the transmission of other ancient, religious texts. For example, the sages believed that the Book of Isaiah originally began with chapter six. In addition, the chronological discrepancies in the Synoptic Gospels themselves attest to the disruption of the story order. The reason for this disruption remains a mystery. Perhaps it had something to do with lectionary readings in the early church.[4]

Viewed together, Papias’ and Luke’s statements offer a glimpse of the stages of transmission for the Gospel materials. They inform us that the original story of Jesus was written in Hebrew, that this story was translated and probably reworked by many individuals, and that somehow the original order of events was obscured.

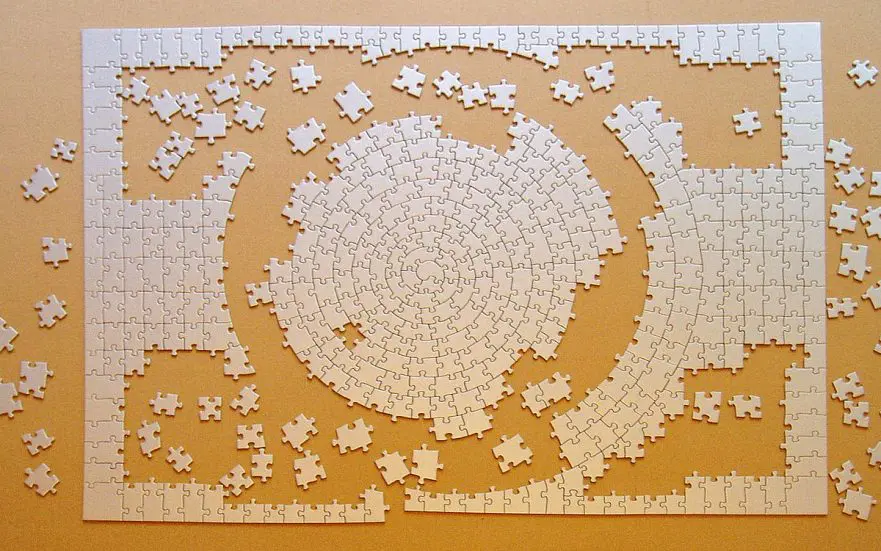

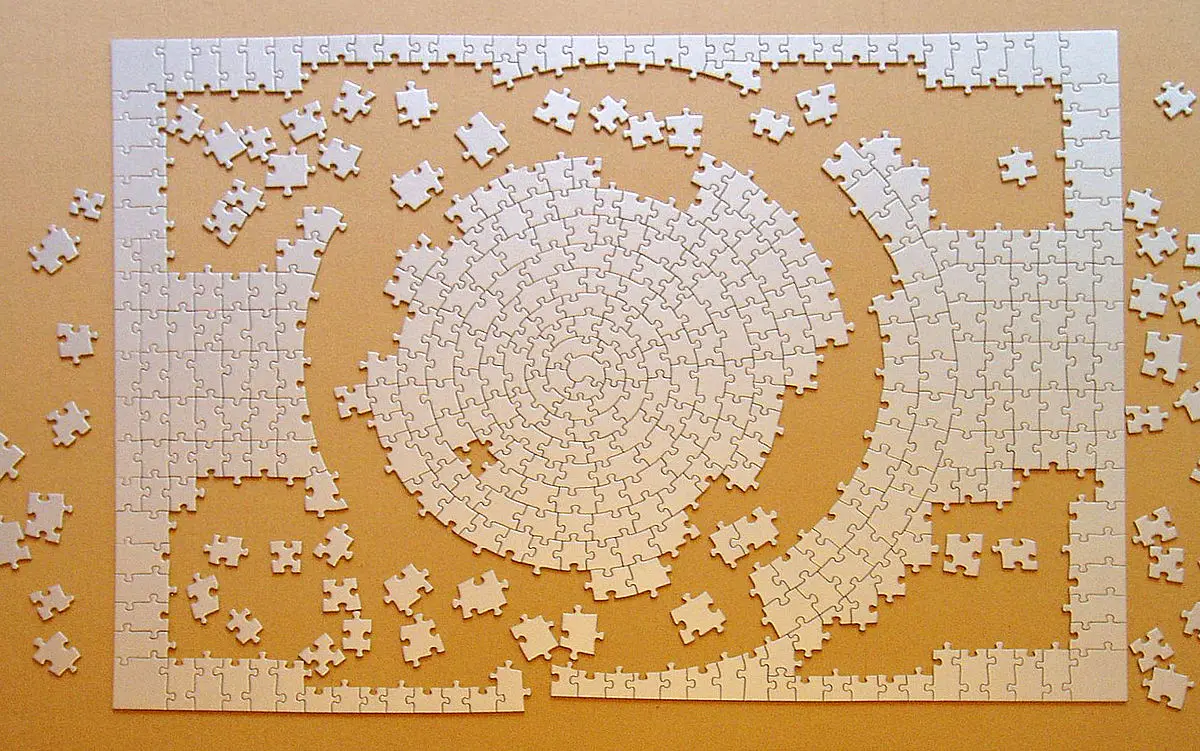

The scenario described above is foundational to Robert Lindsey’s synoptic theory. He believes that Matthew’s composition, like the Pentateuch of the Septuagint, was translated literally into Greek. Then, this translation was rearranged according to literary form: incidents in Jesus’ life, teachings, and parables. In his prologue Luke seems to be describing conditions that resulted from this reorganization.

Once the composition had been rearranged, attempts were made to piece the story back together. Luke decided to use one such attempt, in conjunction with the reorganized text, in writing his Gospel. Mark based his story primarily on Luke’s, though apparently he also knew the reorganized text. The writer of Matthew, who is neither the disciple Matthew nor the Matthew of the Papias tradition, used Mark’s account and the reorganized text.

Interestingly, the attempts to restore order to the events of Jesus’ life do not end with the Synoptic Gospels. Sometime about 160 A.D. Tatian, a disciple of Justin Martyr, composed a harmony of the Gospels known as the Diatessaron. This harmonization became the standard Gospel text of the Syriac-speaking church until the fifth century. The adoption of the Diatessaron by Christians in the East further underscores the liberties that early Christianity allowed in regard to the transmission and reworking of the Gospels.[5]

Despite a rather turbulent transmission process, the Synoptic Gospels retain an astonishing amount of authentic and reliable material. This we know from the internal evidence. Indeed, Luke did not wholly succeed in restoring the original order of the story, as is evident from the success of Lindsey’s reconstructions,[6] but he did transmit in a conservative manner his two Greek sources, one of which contained highly Hebraic material stemming directly from the original Greek translation of the Hebrew.

Image by Puzzle_Krypt.jpg: Muns courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Notes

- Eusebius, Ecclesiastical History III 39, 16. ↩

- Jehoshua Grintz, “Hebrew as the Spoken and Written Language in the Last Days of the Second Temple,” Journal of Biblical Literature 79 (1960): 33. ↩

- M. H. Segal, A Grammar of Mishnaic Hebrew (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1927), 14-15. ↩

- Brad H. Young, Jesus and His Jewish Parables (Mahwah, NJ: Paulist Press, 1989), 145. ↩

- James Kugel and Rowan Greer, Early Biblical Interpretation (Philadelphia: Westminster Press, 1986), 115. ↩

- Robert L. Lindsey, Jesus, Rabbi and Lord: A Lifetime’s Search for the Meaning of Jesus’ Words. ↩