Revised: 21-Apr-2013

Certain circles within the Judaism of Jesus’ day took the view that there was something spiritually beneficial in poverty per se, that it was a mark of God’s special favor to be poor.[1] Given Jesus’ admission that “the Son of Man has come eating and drinking,” and the accusation that therefore he was a “glutton and a drunkard,”[2] it seems unlikely that Jesus would have been accepted in such circles. He possessed too much of the moderation that characterized main-stream Pharisaism.[3]

There are a number of passages in the synoptic gospels which suggest that Jesus may have held extreme views regarding wealth, but on closer examination one finds that this probably was not the case.

No Fixed Abode

And Jesus said, “Foxes have holes, and birds of the air have nests; but the Son of Man has nowhere to lay his head.”[4]

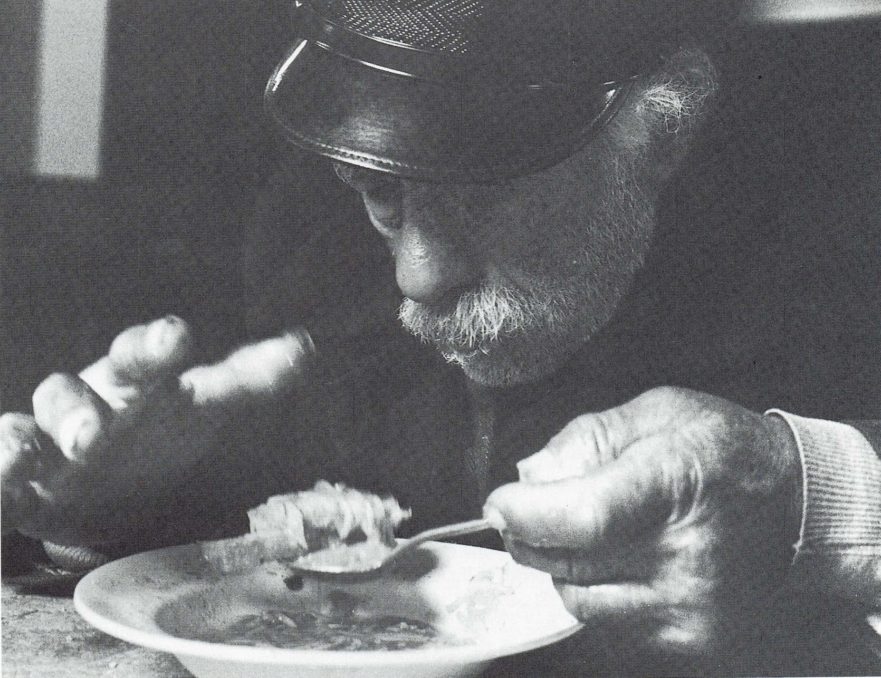

This could indicate that Jesus was abjectly poor. However, it more likely reflects the typical life of a first-century sage who was constantly traveling and thus had no fixed abode.

Paid Content

Premium Members and Friends of JP must be logged in to access this content: Login

If you do not have a paid subscription, please consider registering as a Premium Member starting at $10/month (paid monthly) or only $5/month (paid annually): Register

One Time Purchase Rather Than Membership

Rather than purchasing a membership subscription, you may purchase access to this single page for $1.99 USD. To purchase access we strongly encourage users to first register for a free account with JP (Register), which will make the process of accessing your purchase much simpler. Once you have registered you may login and purchase access to this page at this link:

- [1] The Hasidim were perhaps the most influential proponents of this philosophy in first-century Israel. These were a stream of Galilean sages who were close in theology to the Pharisees while at the same time in tension with them because the Hasidim emphasized the doing of good deeds more than the study of Torah. Shmuel Safrai carried out extensive research on the Hasidim. He contends that Jesus, although not a Hasid, was similar to the Hasidim in many ways. Safrai argues that Jesus, like the Hasidim, idealized poverty: Jesus lived a pauper’s life, and also demanded of his disciples that they give up all their material wealth. See Safrai’s, “Jesus and the Hasidim.”

Many outstanding scholars have held Safrai’s view regarding Jesus’ attitude toward wealth. In his commentary on the synoptic gospels, Claude Montefiore quotes Kirsopp Lake (apparently in agreement with Lake): “Professor Lake has said: ‘I think Jesus clearly taught that riches ought to be rejected and given to the poor. He not only said so quite definitely to the rich man who asked his advice, but he denied the possibility (apart from the special act of God) that rich men can enter the Kingdom of Heaven. I have not the smallest doubt but that Jesus said this and meant it. I do not believe that he meant it as exceptional teaching. Poverty was his rule of life, yet I do not think it is the right rule of life, or that it is practicable if civilization is to continue’ (The Religion of Yesterday and Tomorrow [1925], p. 155)” (C. G. Montefiore, The Synoptic Gospels, [2d ed.; London: Macmillan & Co., 1927], 2:559-60).

Vincent Taylor comments on Mark 10:21: “Commentators are right in saying that Jesus does not demand the universal renunciation of property, but gives a command relative to a particular case. Nevertheless, as Lohmeyer, 211, points out, Jesus Himself appears to have chosen a life of poverty; He wanders to and fro without a settled home (Mk. i. 39, Lk. ix. 58), His disciples are hungry (Mk. ii. 23, viii. 14), women provide for His needs (Lk. viii. 3), and His disciples can say Ἰδοὺ ἡμεῖς ἀφήκαμεν πάντα καὶ ἠκολουθήκαμέν σοι [Behold we left everything and followed you] (Mk. x. 28)” (The Gospel according to St. Mark [London: Macmillan & Co., 1952], 429). Here, Taylor first seems to agree that Jesus did not idealize poverty, then qualifies his view by quoting another scholar.

Shmuel Safrai has noted: “Hasiduth [the belief and practice of the Hasidim] is generally associated with the conception of humility” (“Teaching of Pietists in Mishnaic Literature,” The Journal of Jewish Studies 16 [1956]: 17, note 13). It seems likely that in a number of rabbinic passages the word עֲנִיּוּת (aniyut) refers not to poverty but to humility. This certainly is true of its usage in Seder Eliyahu Zuta 3 (p. 176), where the poor “whom humility [not poverty] becomes” are contrasted with the haughty:

Scripture says: “You will save a humble people, but your eyes are on the haughty to bring them low” [2 Sam. 22:28]. “You will save a humble people”—this refers to the people [of Israel] whom humility becomes. “Your eyes are on the haughty to bring them low”—these are the [heathen] nations of the world.

Notice how much stronger is the saying of Elijah in the Babylonian Talmud, Hagigah 9b, when aniyut is taken to mean humility rather than poverty:

The Holy One, blessed be he, went through all the good qualities and the only one which he found that was good enough to give to Israel was humility.

Even the popular saying recorded in Leviticus Rabbah 13, “Humility becomes Israel like a red strap across the breast of a white horse,” falls flat if aniyut is translated as poverty. ↩

- [2] Matt 11:19. ↩

- [3] For an excellent survey of the Pharisaic view that, in general, poverty is an evil, see Israel Abrahams’ chapter, “Poverty and Wealth,” in Studies in Pharisaism and the Gospels (2 vols.; Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1917, 1924; repr. in one volume by Ktav Publishing House, New York, 1967), 1:113-117. ↩

- [4] Matt 8:20; Luke 9:58. ↩