A lively group of children are grinding wheat kernels between two stones, in preparation for baking their own pita-bread. In a nearby grainfield, visitors are searching for tares among the wheat. Another group are tasting ripe sycamore figs and learning why it was a sycamore tree that Zacchaeus climbed in Jericho. Under a grape arbor in “Isaiah’s Vineyard,” yet another group of visitors are munching ripe, sun-warmed fruit as their guide explains the vine-to-wine process and the symbolism of the grape.

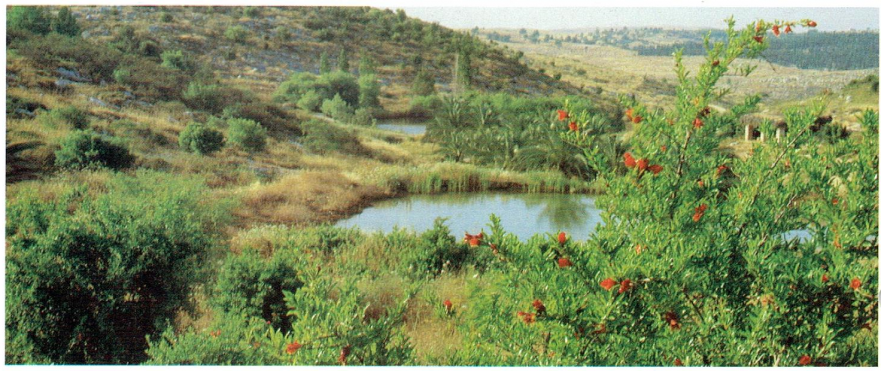

This is Neot Kedumim, 625 acres of reconstructed biblical landscapes in Israel’s Modi’in region (2,000 years ago home to the Maccabees, today ten minutes from Ben-Gurion Airport).

Paid Content

Premium Members and Friends of JP must be logged in to access this content: Login

If you do not have a paid subscription, please consider registering as a Premium Member starting at $10/month (paid monthly) or only $5/month (paid annually): Register

One Time Purchase Rather Than Membership

Rather than purchasing a membership subscription, you may purchase access to this single page for $1.99 USD. To purchase access we strongly encourage users to first register for a free account with JP (Register), which will make the process of accessing your purchase much simpler. Once you have registered you may login and purchase access to this page at this link:

“Neot” means pastures or places of beauty (as in Ps. 23, “He makes me lie down in green pastures”). “Kedumim” meaning ancient, also contains the Hebrew root that indicates forward motion in time, and expresses the biblical landscape reserve’s underlying philosophy of future growth based on understanding of past roots.

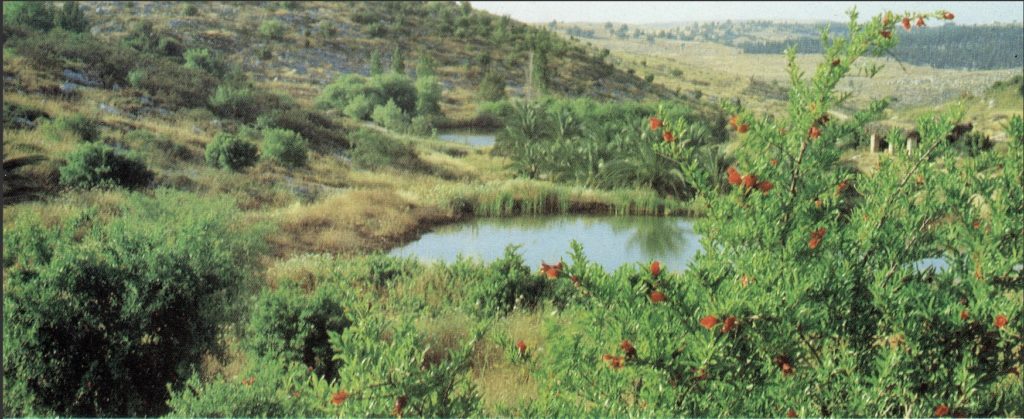

Neot Kedumim is, strictly speaking, not a nature reserve but a partnership between human effort and the forces of nature. The tract allocated by the Israeli government in 1965 had nothing to preserve; centuries of overgrazing, battles, and neglect had eroded the land down to bare rock. Founder Nogah Hareuveni and what was at first a handful of dedicated people began by trucking in thousands of tons of soil, reconstructing ancient terraces to hold it, and digging reservoirs to catch the precious rainwater. This effort has been recognized worldwide as a model of “restoration ecology”—the reconstruction of landscapes human activity has destroyed.

Today, miles of comfortable, wheelchair accessible paths crisscross the hills and valleys in the gently rolling land of the Shephelah, where the Judean Hills start rising from the flat coastal plain.

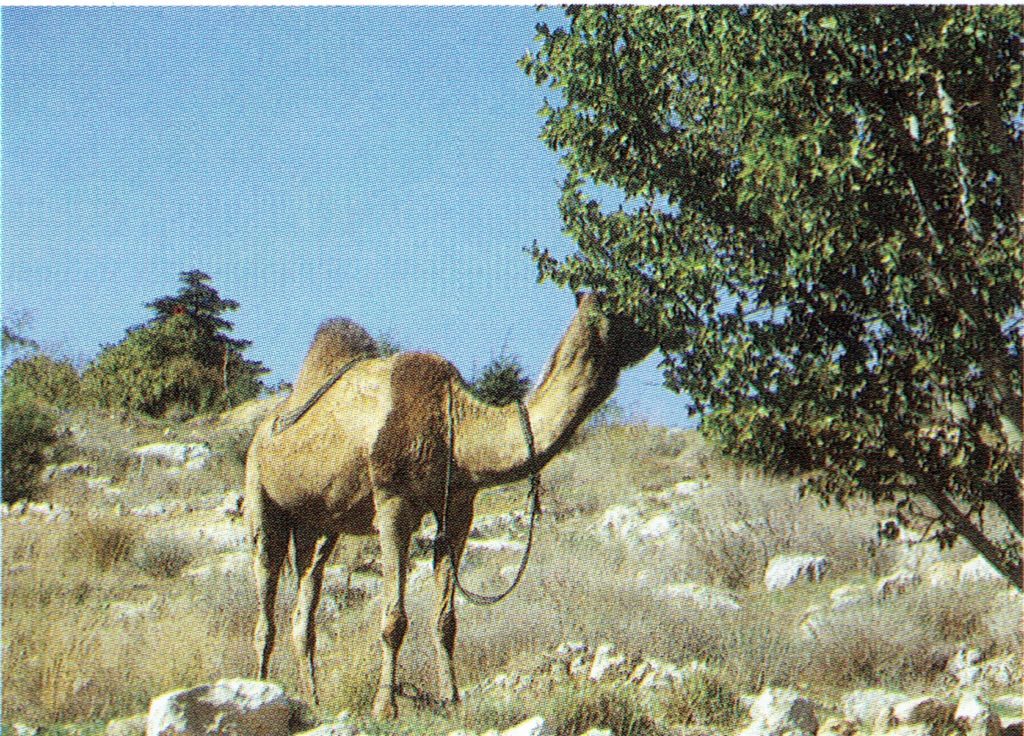

Along with hundreds of varieties of plants are ancient and reconstructed olive and wine presses, threshing floors, cisterns and ritual baths. A camel, sheep, goats, and cows of the native, lean variety graze in the fields. “Sukkah” shelters protect visitors from the rain or sun, according to the season. “Woodland stages” surrounded by wooden benches seating up to 1,500 persons offer a pastoral setting for special events.

What becomes clear at Neot Kedumim is that while the universal messages of Scripture echo around the world, the text, in all its hundreds of translations, always speaks in a particular idiom—that of Israel’s nature and agriculture.

Walking through the reconstructed olive groves, vineyards, and grainfields at Neot Kedumim, sitting in the shade of its transplanted date palms, enjoying the fragrance of the myrtle and hyssop that now flourish in its rolling hills, this “ancient Esperanto”—the language of Israel’s ecology—lives for us as it did for our agrarian forebears, the people of the Scriptures. —JP