Jesus’ warning to beware of the ζύμη (zūmē, “leaven,” “leavened bread”)[1] of the Pharisees has perplexed audiences since before the Gospels were written. Each of the synoptic evangelists interpreted the warning differently, and there is disagreement among the evangelists regarding the context of Jesus’ warning.

In Mark’s Gospel Jesus’ warning is embedded in a story about how the disciples forgot to bring bread with them on the boat as they crossed the Sea of Galilee with Jesus. When Jesus warns them about leavened bread, the disciples assume it is because they had forgotten to bring bread for the journey. Jesus, however, castigates the disciples for their lack of understanding and interrogates them about the two miraculous feedings they had witnessed. The pericope closes with Jesus asking the disciples, “Do you still not understand?”

The way Jesus’ warning stands out from the rest of Mark’s pericope has led scholars to suggest either that the author of Mark inserted the warning about leavened bread into the story about how the disciples forgot to bring bread with them and failed to understand that the man who had miraculously fed the multitudes could easily provide for the disciples, or that the author of Mark constructed the story about the disciples’ forgetfulness and lack of understanding in order to provide Jesus’ warning about leavened bread with a context.

Matthew’s placement of Jesus’ warning is the same as Mark’s, but the author of Matthew gave the warning a novel interpretation. Whereas the author of Mark implied that failure to understand Jesus’ miracles was itself the “leavened bread of the Pharisees,” the author of Matthew identified the leavened bread as Jewish teaching. The author of Matthew did not want his readers to respect the authority of Jewish teachers unless those Jewish teachers were also Christians.

In Luke’s Gospel Jesus’ warning lacks the narrative framework it possesses in Mark and Matthew. It merely appears as the first saying in a longer discourse about the trials the disciples will face in the future. Its placement in Luke appears entirely artificial, being governed by the series of woes against the scribes and Pharisees that appeared in the preceding pericope. An explanatory gloss appears in Luke’s version of Jesus’ warning against the leaven/leavened bread of the Pharisees that identifies ζύμη as hypocrisy. However, there are reasons to suspect that this explanatory gloss did not belong to the original text of Luke. The phrase “which is hypocrisy” appears at different locations within the sentence in different witnesses to Luke 12:1. There is also the fact that the author of Luke never accuses the Pharisees of hypocrisy anywhere else in his writings (the Gospel of Luke and the Acts of the Apostles). It is possible, therefore, that the explanatory gloss originated as a marginal note written by some scribe that later copyists incorporated into the text. If so, then the author of Luke simply regarded Jesus’ warning as an enigmatic saying for which he provided no interpretation.

Most scholars agree that since its original context has been lost, the original meaning of Jesus’ warning is beyond recovery. Often it is asserted that the way leaven permeates dough, causing it to rise through the process of fermentation, must be the point of comparison. Like leaven, the Pharisees have a pervasive corrupting influence.

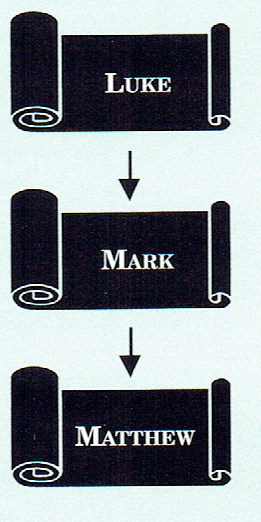

Robert Lindsey’s approach to the Synoptic Problem opens up new avenues for understanding Jesus’ enigmatic warning. Observing the way Luke’s Greek generally reverted to Hebrew more easily than the Markan parallels, Lindsey came to the conclusion that Luke’s Gospel must be closer than Mark’s to a pre-synoptic source, which was a Greek translation of a Hebrew biography of Jesus. Lindsey also realized that Luke’s Greek source must have separated and rearranged stories, sayings and illustrations that were connected in the Hebrew original. By carefully examining verbal and thematic clues, Lindsey argued that it was possible to reconstruct from the Lukan fragments the larger units that had existed in the original Hebrew source. Mark’s Gospel, Lindsey concluded, was a condensed version of Luke that was paraphrased into popular style. Following Lindsey’s approach, we can see that Luke’s shorter version of Warning About Leavened Bread, minus the explanatory gloss, is the most primitive and that Mark’s framing of Jesus’ warning is indeed secondary. Matthew’s version of the pericope, which contains two versions of Jesus’ warning (Matt. 16:6, 11), exhibits minor agreements with Luke 12:1 that confirm Luke’s more primitive wording.

Once Luke’s wording is established as the most reliable, our attention is drawn to the fact that another warning of Jesus in Luke contains similar vocabulary and grammatical structure:

προσέχετε ἑαυτοῖς ἀπὸ τῆς ζύμης…τῶν Φαρισαίων

Beware for yourselves of the leaven[ed bread]…of the Pharisees! (Luke 12:1)

προσέχετε ἀπὸ τῶν γραμματέων τῶν…φιλούντων…πρωτοκλισίας ἐν τοῖς δείπνοις οἳ κατεσθίουσιν τὰς οἰκίας τῶν χηρῶν….

Beware of the scribes who…love…first couches in the banquets, those who devour the houses of widows…! (Luke 20:46-47)

Since scribes and Pharisees are often associated with one another in the Gospels, it is not unreasonable to suppose that these two warnings originally belonged to the same literary context and they are mutually illuminating. The wicked practices described in the second warning show what is meant by leaven/leavened bread in the first warning, while the reference to the Pharisees in the first warning shows that it is Pharisaic scribes that are the target of the second warning.

Associating the two similarly worded warnings with one another also opens up the possibility of an underlying wordplay. The Hebrew word for leavened bread, חָמֵץ (ḥāmētz), which the LXX translators often rendered as ζύμη (zūmē, “leaven,” “leavened bread”) and which occurs in Jesus’ first warning, sounds like the noun חָמָס (ḥāmās, “extortion”), a term that might be used to describe the corrupt financial practices attributed to the scribes (viz., devouring widow’s homes) in the second warning.

Jesus’ second warning, in a pericope we call Making a Show, contains a distinctive term, πρωτοκλισία (prōtoklisia, “first couch”), that occurs in only one other pericope, Places of Honor (Luke 14:7-11). There Jesus advises his audience not to assume for oneself the πρωτοκλισία at a banquet but to take the last place. That way, one will avoid the risk of embarrassment in case the host had reserved the “first couch” for another while simultaneously positioning oneself for potential promotion in case the host should wish to do him honor.

The advice Jesus gives in Places of Honor fits well with the warning he issues in Making a Show. Listeners should beware of the unseemly behavior of the Pharisaic scribes, who arrogate honors to themselves while trampling on the rights of others. Listeners should instead act with humility and grace, which will earn them enduring respect within their communities.

Since these three pericopae fit together so well, we have included them in a complex we call “Showing Proper Humility.” It appears that the sayings in this complex were addressed to a general audience rather than specifically to disciples. We have therefore positioned this complex at an early stage in Jesus’ public ministry prior to his calling and training of disciples.

Although we feel confident that the three pericopae included in the “Showing Proper Humility” complex originally belonged together, we are by no means certain that we have recovered the entire discourse to which they belonged or that it is possible to do so. Some sayings of Jesus have undoubtedly been lost and some connections are irrevocably broken.

Click on the following titles to view the Reconstruction and Commentary for each pericope in the “Showing Proper Humility” complex.

Warning About Leavened Bread

Warning About Leavened Bread

Making a Show

Making a Show

Places of Honor

Places of Honor

Click here to return to The Life of Yeshua: A Suggested Reconstruction main page.

_______________________________________________________

Click here to return to The Life of Yeshua: A Suggested Reconstruction main page.

_______________________________________________________

- [1] Translating ζύμη as “yeast” is anachronistic, since yeast extraction for baking is a modern process. In the ancient world breads were leavened with a fermenting sourdough starter. The fermentation of the starter dough was caused by yeasts and bacteria that naturally occurred in the flour. See the LOY segment, Mustard Seed and Starter Dough parables, Comment to L31. ↩