How to cite this article: Lois Tverberg, “He Could No Longer Openly Enter a Town: A Synoptic Study in Light of an Early Luke,” Jerusalem Perspective (2024) [https://www.jerusalemperspective.com/28817/].

This article belongs to the collection Ashrech Ziqnati (Blessed Are You, My Old Age): Studies in Honor of David Bivin’s 85th Birthday.

| Rather listen instead? |

| JP members can click the link below for an audio version of this essay.[*]

Paid Content

Premium Members and Friends of JP must be signed in to view this content. If you are not a Premium Member or Friend, please consider registering. Prices start at $5/month if paid annually, with other options for monthly and quarterly and more: Sign Up For Premium  |

I am greatly honored to be asked to contribute to this volume honoring David Bivin, a beloved mentor and source of wisdom to me for over twenty-five years now. David is a meticulous researcher who has devoted his scholarship to understanding Jesus in light of his original first-century Jewish context. He taught me about the rabbi/disciple relationship, and indeed he showed me what it looks like by pouring his life into the task of discerning his Master’s words accurately so that he could live them out.

About twenty years ago I began working with David on editing a selection of his Jerusalem Perspective articles for a book that my ministry named New Light on the Difficult Words of Jesus.[1] I had the delightful task of choosing which of David’s articles to include that would have wide appeal to Christians interested in Jesus’ Jewish context. I have to admit—I avoided including his research on synoptic relationships, even though David had spent an enormous amount of time on this topic. I knew that it would be too challenging for conservative Christians. I myself had not read much source-critical study on the Gospels because my Ph.D. is in molecular biology, not New Testament studies.

Now, however, after twenty years of writing on the popular level about the Jewishness of Jesus, I have spent much more time reading academic commentaries on biblical literature, and I see how important David’s study of the Synoptic Problem is for understanding Jesus.

I now see how the default assumption that Mark is the “primitive original” that the other synoptic writers edited is often a problem for understanding the Jewish context of Jesus. To most New Testament scholars today, Mark’s Gospel is the final authority on Jesus’ life, even though it is the least Jewish of all the Gospels. Luke is assumed to be a late, unfaithful redactor of Mark whenever they disagree. Even conservative commentators who assume that Matthew was the first Gospel read Luke as the last and least helpful redactor.

This trend continues despite the evidence that suggests that Luke’s Gospel was written quite early. Luke alone notes very early geopolitical realities that ended before 40 C.E., like the fact that Herod Antipas was tetrarch of Galilee, which ended in 39 C.E., and that Lysanias was tetrarch of Abilene, which ended in 36 C.E. (Luke 3:1).[2] Luke’s Gospel also does not use place names like “Gethsemane” (Matt. 26:36, Mark 14:32) and “Golgotha” (Matt. 27:33, Mark 15:22, John 19:17), that are otherwise unattested in contemporary sources, so likely came from the early church.[3] Luke also does not refer to the Decapolis (Matt. 4:25, Mark 5:20; 7:31), the federation of Greco-Roman city-states that was established during the Jewish revolt of 70 C.E. and not mentioned by historians before then.[4]

Of course Matthew is known for the Jewishness of his narrative, but Luke has been vastly underappreciated as a resource. Luke carefully records much rich detail about Jesus’ pious Jewish upbringing and lifestyle, and is a critical witness to the antiquity of Jewish customs. The fact that Jesus was named on the eighth day when he was circumcised (Luke 1:59, 2:21) is the first recorded observance of this tradition,[5] as well as his reading from the Haftarah (the prophetic portion that follows the Torah reading) before preaching in the synagogue in Nazareth (Luke 4:16-27).[6] Both of these important Jewish practices persist until this day, but are not mentioned until centuries later in Jewish sources.

It’s hard not to wonder if the universal overemphasis on Mark and the constant disparagement of Luke as a historical source is part of why many Christians have so little appreciation of Jesus’ Jewish context. Now I see the importance of David’s work on the synoptic relationships and his efforts to reconstruct a tentative “Life of Yeshua” text that contains early, Hebraic stories and teachings translated very literally into Greek.

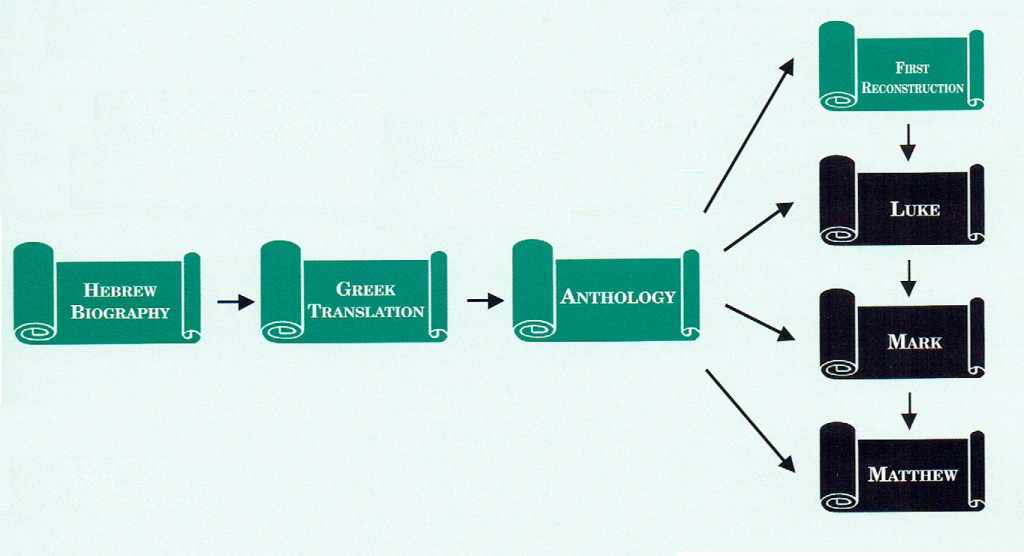

For those unfamiliar with David Bivin’s work, let me briefly explain the theory he uses.[7] Since the 1960’s, David has been studying the Synoptic Gospels with a group of Christian and Jewish scholars who employ two tools unavailable to most New Testament scholars: an internal fluency in Hebrew and Aramaic and a deep familiarity with early Jewish literature. With these tools they can sense when the Greek text of a Gospel account is reflecting the wording of a Semitic, Jewish-sounding original or has undergone editing into a smoother Greek.[8]

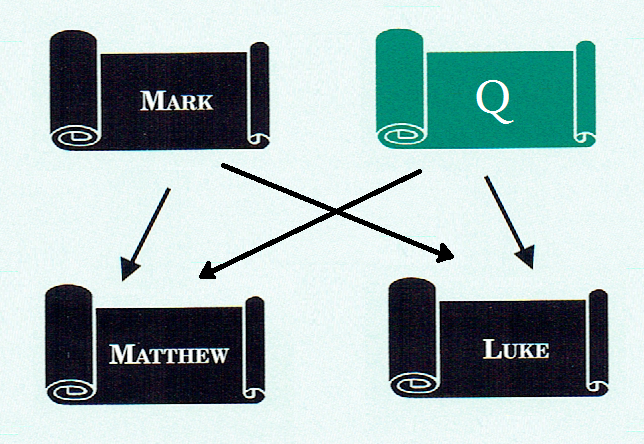

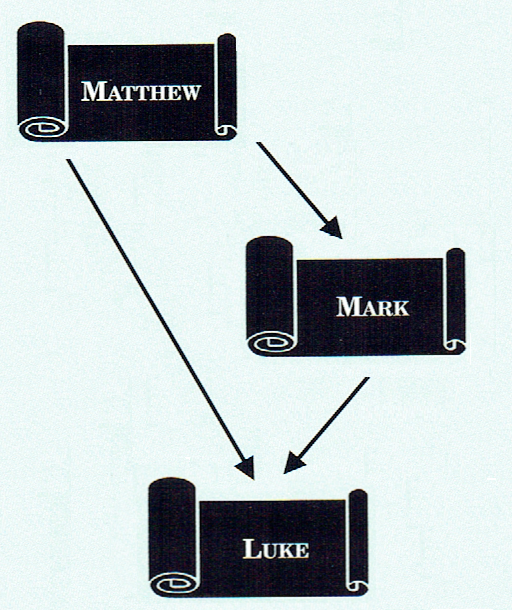

The group actually began their work using the assumptions of Markan Priority, the idea that Mark was written first and used as a source by Matthew and Luke (along with other sources). However, they soon discarded much of this theory when they found numerous places where Mark had re-edited texts for which a more Hebraic, Jewish sounding original was better preserved in Luke or Matthew. They agreed that Matthew had used Mark as a source, but Luke had not. David and his mentor, Robert Lindsey, believed that it was more likely that Mark had used Luke as a source rather than the reverse. Others of the group believe that Luke was simply written independently of Mark, and similar texts come from a shared Hebraic-Greek source that Luke followed carefully, but that Mark modified freely. Matthew also accessed this text, but he preferred to use Mark as his source when it was available. Sometimes, however, he and Luke would agree against Mark to preserve a much more Hebraic-sounding original.[9]

Although I cannot access original languages well enough to do synoptic study at the level that David does, I would like to share an observation I made using his assumptions about synoptic relationships that makes much more sense to me than what I have found in New Testament scholarship otherwise. I hope this study spurs others to ask similar questions.

Entering or Leaving Jericho?

The conventional method of studying the Synoptic Gospels is to read each parallel text assuming that Matthew and Luke modified Mark. Then every commentary is full of conundrums about what could have motivated Luke to modify Mark’s story, and a generalized distrust in Luke as a source.

An interesting example occurs in the pericope of Jesus healing a blind beggar near Jericho, which is in Matthew 20:29-34, Mark 10:46-52 and Luke 18:35-43. Mark presents the scene as occurring as Jesus leaves the city:

Premium Members and Friends of JP must be signed in to view this content.

If you are not a Premium Member or Friend, please consider registering. Prices start at $5/month if paid annually, with other options for monthly and quarterly and more: Sign Up For Premium

Notes

- David N. Bivin, New Light on the Difficult Words of Jesus: Insights from His Jewish Context (Holland, MI: En-Gedi Resource Center, 2005).[↩]

- Several scholars accused Luke of being in error about the existence of a Lysanias who was tetrarch in the first century until two inscriptions with his name were found at the site of Abila, the capital of the tetrarchy of Abilene. See Raphaël Savignac, “The Complete Text of the Abila Inscription Concerning Lysianias” at WholeStones.org.[↩]

- All these pieces of evidence were discussed in Steve Notley’s presentation, “Luke in Historical Geography” at the Society for Biblical Literature Conference on November 21, 2021. Notley additionally noted another difference between Luke and the rest of the Gospels, which is that instead of referring to ἡ θάλασσα τῆς Γαλιλαίας (hē thalassa tēs Galilaias, “the Sea of Galilee”) he instead uses the term λίμνη Γεννησαρὲτ (limnē Gennēsaret, “lake of Gennesaret”), which is the name used by Josephus, Strabo and other early historians. “Sea of Galilee” was not otherwise attested until the Byzantine period, so was also likely adopted by early Christians. See R. Steven Notley, “The Sea of Galilee: Development of an Early Christian Toponym” Journal of Biblical Literature 28.1 (2009): 183-188.[↩]

- See Anson Rainey and R. Steven Notley, The Sacred Bridge (Jerusalem: Carta, 2006), 362.[↩]

- See Shmuel Safrai, “Naming John the Baptist” (Jerusalem Perspective 20 (May 1989): 1-2 [https://www.jerusalemperspective.com/2342/].[↩]

- Shmuel Safrai, “Synagogue and Sabbath,” Jerusalem Perspective 23 (Nov 1989): 8-10 [https://www.jerusalemperspective.com/2424/]; R. Steven Notley, “First-century Jewish Use of Scripture: Evidence from the Life of Jesus” Jerusalem Perspective (Jan 1, 2004) [https://www.jerusalemperspective.com/4309/].[↩]

- A much more detailed explanation is available in David N. Bivin, “Introduction to The Life of Yeshua: A Suggested Reconstruction” (Jerusalem Perspective, 2013) [https://www.jerusalemperspective.com/743/) under the subheading “A New Approach to the Synoptic Gospels.”[↩]

- Many erroneously assume that Jesus spoke Aramaic only. After discovering that the Dead Sea Scrolls included an overwhelming number of Hebrew texts (550) along with some in Aramaic (120) and a few in Greek (28), scholars now believe that Hebrew was a living language in the first century and Jesus spoke both, and likely did his teaching in Hebrew. The Semitic Greek that Bivin and his group encountered in the Synoptics contained largely Hebraisms, not Aramaisms, as others theorized. It is also not the product of an artificial “Septuagintalizing” style employed by Luke. For an extensive discussion of the trilingual language environment of the Gospels, see The Language Environment of First Century Judea (Randall Buth and R. Steven Notley, eds.; Leiden, Brill: 2014).[↩]

- Robert Lindsey, “The Major Importance of the Minor Agreements” Jerusalem Perspective (Feb. 20, 2015) [https://www.jerusalemperspective.com/13766/].[↩]

Comments 1

That was really good. Thank you. Love your books.