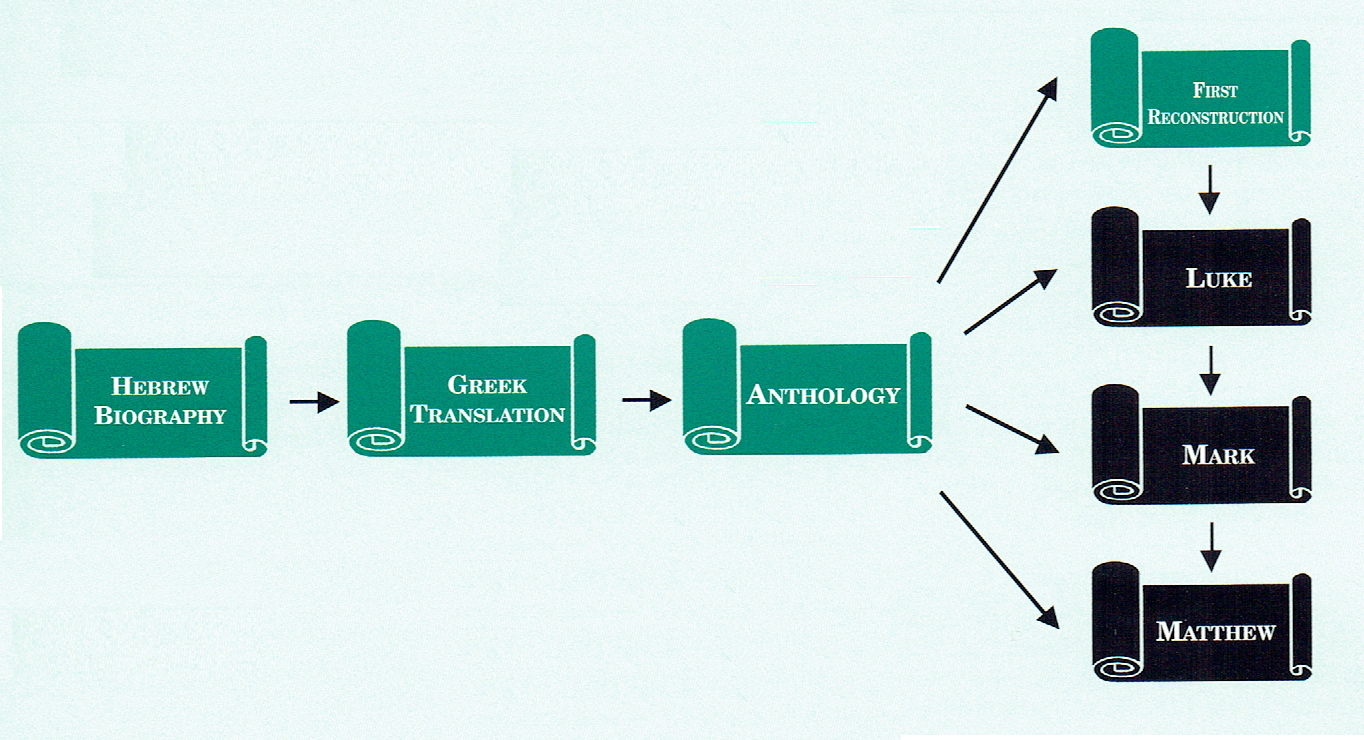

| 1. Hebrew Life of Jesus (36-37 A.D.) Jesus’ words were recorded in Hebrew within about five years of his death. This was a straightforward Hebrew story, about thirty to thirty-five chapters long, similar to the simple biographies of Elijah and Elisha in the Hebrew Scriptures. 2. Greek Life of Jesus (41-42 A.D.) Within the next five years, Greek-speaking congregations inside and outside the land of Israel demanded a Greek translation of Jesus’ biography. As was typical of the period, this Greek translation was slavishly literal. Also, Greek being less concise than Hebrew, the Greek work was ten to twelve chapters longer than the Hebrew source from which it was translated. 3. Reorganized Scroll = Anthology (43-44 A.D.) Before the Greek Life of Jesus was widely circulated, its various stories were reorganized topically: opening incidents were collected from teaching-context stories and, together with miracle and healing stories, placed at the beginning of the new scroll; discourses were collected from the teaching-context stories and placed in the second section of the scroll (these discourses were often grouped on the basis of common key words); twin parables, normally the conclusion to teaching-context stories, were collected and placed in the third and final section of the scroll. Thus parts of the Greek translation were divorced from their original contexts and the original story outline was lost. Even stories were sometimes divided and the fragments moved to different contexts. 4. First Recreated Story = First Reconstruction (55-56 A.D.) Shortly before Luke wrote his account, a Greek author attempted to reconstruct a chronological record based upon the fragments of the Reorganized Scroll. This resulted in a much shorter version of Jesus’ biography (a condensation of about eighteeen chapters), as well as a significant improvement in its quality of Greek. 5. Gospel of Luke (58-60 A.D.) The author of Luke used both the Reorganized Scroll (Anthology) and the First Reconstruction in writing his Gospel. As specifically stated in his prologue, Luke desired to present an “orderly account” of Jesus’ life, and took his cue for much of his story outline (chapters 3-9 and 18-24) from the First Reconstruction. Of the synoptic Gospel writers, only Luke seems to have known the First Reconstruction directly. 6. Gospel of Mark (65-66 A.D.) The author of Mark, who apparently also had access to the Reorganized Scroll (Anthology), reworded the stories he took from Luke’s Gospel, altering more than fifty percent of Luke’s wording. Despite being familiar with the Anthology, the author of Mark rarely made use of its wording, preferring to draw his substitute words from other sources such as borrowing phrases from Acts, Romans, 1 and 2 Corinthians, Colossians, 1 and 2 Thessalonians, and James, as well as unused parts of Luke. But by comparing Luke to the Anthology the author of Mark could identify the stories Luke took from the First Reconstruction, the stories that gave Luke’s Gospel its chronology. It is mainly these chronologically arranged stories that the author of Mark drew upon when composing his own Gospel. The First Reconstruction was unknown to the author Mark directly. 7. Gospel of Matthew (68-69 A.D.) The author of Matthew used as sources both Mark’s Gospel and the Reorganized Scroll (Anthology), trying to be faithful to both where the two sources differed. When he took stories from the Anthology that were not present in Mark, the author of Matthew inserted them into the chronological story order he inherited from Mark’s Gospel. Because Matthew’s chronology came from Mark and Mark’s from Luke, the chronology of Matthew and Mark is indirectly derived (through Luke) from the First Reconstruction. The author of Matthew did not know the First Reconstruction or the Gospel of Luke directly. |