How to cite this article: Joshua N. Tilton, “Two Kinds of Love in the Story of the Paralyzed Man,” Jerusalem Perspective (2025) [https://www.jerusalemperspective.com/30025/].

| Rather listen instead? |

| JP members can click the link below for an audio version of this essay.[*]

Paid Content

Premium Members and Friends of JP must be signed in to view this content. If you are not a Premium Member or Friend, please consider registering. Prices start at $5/month if paid annually, with other options for monthly and quarterly and more: Sign Up For Premium  |

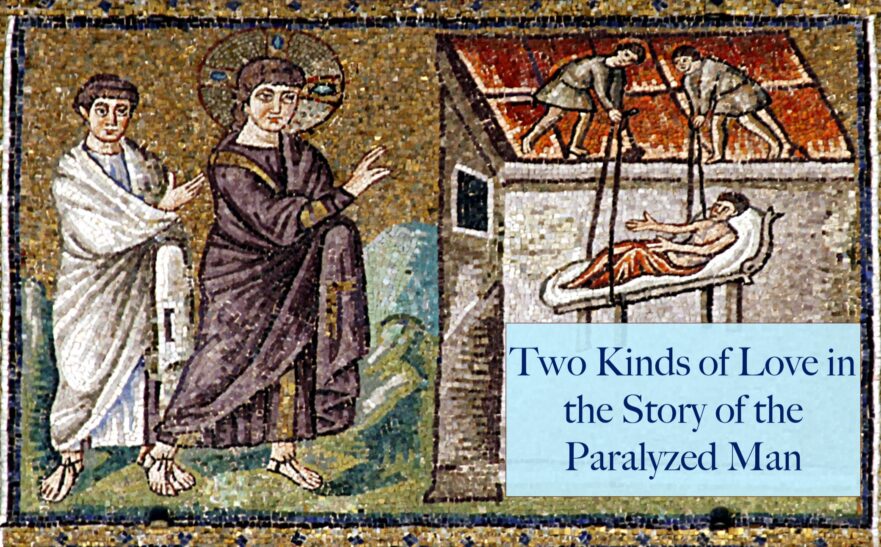

Many JP readers have known the story of the paralyzed man since Sunday School (Matt. 9:2-8; Mark 2:1-12; Luke 5:17-26).[18] The memorable image of the men digging a hole through the roof of the house and lowering their friend down on his bed before the feet of Jesus in order to bypass the crowds captures the imagination. As the story unfolds, Jesus declares that the paralyzed man’s sins are forgiven, but some bystanders accuse Jesus of speaking blasphemy. Yet, when Jesus commands the paralyzed man to get up, take his mat and walk, and the paralyzed man miraculously obeys, Jesus’ critics are confounded, and the crowds acclaim Jesus as their hero.

So familiar are the details of the story that we can easily forget to ask what motives, convictions and aims are behind the strange responses of Jesus to the unusual behavior of the paralyzed man and his friends, and of his critics to Jesus’ seemingly innocuous proclamation of forgiveness. Why was Jesus so nonchalant about the friends’ destruction of other people’s property? What was really at stake in the tussle over the forgiveness of sins? Is the most important lesson of the story that Jesus is the Son of Man, who has authority to forgive sins?[19] Or does the story intend to reorient the reader’s perceptions and behaviors in a particular direction?

Premium Members and Friends of JP must be signed in to view this content.

If you are not a Premium Member or Friend, please consider registering. Prices start at $5/month if paid annually, with other options for monthly and quarterly and more: Sign Up For Premium

- [1] On this pattern of behavior that Jesus exhibited, see Joshua N. Tilton, Jesus’ Gospel: Searching for the Core of Jesus’ Message (Jerusalem Perspective: 2012), 72-74. ↩

- [2] In many Bible translations the disease with which the man was afflicted is erroneously called “leprosy.” “Scale disease” is the term biblical scholars use to denote the ritually defiling skin condition mentioned in the Scriptures. ↩

- [3] On the positive view of Israel expressed in Luke’s version of the saying (Luke 7:9) versus the anti-Jewish view of Israel inherent in Matthew’s form (Matt. 8:10), see David Flusser, “Two Anti-Jewish Montages in Matthew,” in his Judaism and the Origins of Christianity (Jerusalem: Magnes, 1988), 552-560, esp. 556. ↩

- [4] See David Flusser, “A Lost Jewish Benediction in Matthew 9:8,” in his Judaism and the Origins of Christianity (Jerusalem: Magnes, 1988), 535-542, esp. 536-537. ↩

- [5] The same pattern appears in the Prayer of Nabonidus, where the Jewish exorcist first forgives the king and only then obtains healing. ↩

- [6] See Menchem Stern, “Zealots,” Encyclopaedia Judaica Year Book 1973 (Jerusalem: Keter, 1973), 135-152; Uriel Rappaport, “Who Were the Sicarii?” in The Jewish Revolt against Rome: Interdisciplinary Perspectives (ed. Mladen Popović; Leiden: Brill, 2011), 323-342. ↩

- [7] On Yohanan ben Zakkai’s opposition to militant Jewish nationalists, see Shimon Applebaum, “The Zealots: The Case for Revaluation,” Journal of Roman Studies 61 (1971): 155-170, esp. 161. Applebaum used “Zealot” as a blanket term for first-century Jewish revolutionary groups including the Fourth Philosophy. ↩

- [8] In rabbinic sources “Sicarii” and “Zealot” are regarded as interchangeable. See Applebaum, “The Zealots: The Case for Revaluation,” 164; Stern, “Zealots,” 137. ↩

- [9] Jos., J.W. 2:56; Ant. 17:271-272. On equating Judah son of Hezekiah with Judah the Galilean, see Stern, “Zealots,” 136; Rappaport, “Who Were the Sicarii?” 331. ↩

- [10] Cf. R. Steven Notley, “First-century Jewish Use of Scripture: Evidence from the Life of Jesus,” Jerusalem Perspective (2004) [https://www.jerusalemperspective.com/4309/], under the subheading “Jesus’ Reception in Nazareth.” ↩

- [11] On the emergence of this enlightened view, see David Flusser, “A New Sensitivity in Judaism and the Christian Message,” in his Judaism and the Origins of Christianity (Magnes: Jerusalem, 1988), 469-489. See also R. Steven Notley, “Jesus’ Jewish Command to Love,” Jerusalem Perspective (2004) [https://www.jerusalemperspective.com/4433/]. ↩

- [12] On this Ben Sira passage as an interpretation of the love command, see David Flusser, “Jesus, His Ancestry, and the Commandment of Love,” in Jesus’ Jewishness: Exploring the Place of Jesus in Early Judaism (ed. James Charlesworth; New York: Crossroad, 1991), 153-176, esp. 169; Serge Ruzer, “From ‘Love Your Neighbour’ to ‘Love Your Enemy’: Trajectories in Early Jewish Exegesis,” Revue Biblique 109.3 (2002): 371-389, esp. 376-378. ↩

- [13] A saying that Clement of Rome attributed to Jesus sums up this two-way relationship in the following manner: “Be merciful, that ye may obtain mercy. Forgive, that ye may be forgiven. As ye do, so shall it be done to you. As ye give, so shall it be given unto you. As ye judge, so shall ye be judged. As ye are kind, so shall kindness be shewn you. With what measure you mete, it shall be measured to you” (1 Clem. 13:2). Translation according to Kirsopp Lake, The Apostolic Fathers (2 vols.; Loeb; Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1912; repr. 1998), 1:31. Flusser (“Jesus, His Ancestry, and the Commandment of Love,” 168) noted the similarity between “As ye do, so shall it be done to you [i.e., by God]” in Clement’s saying and “Do unto others as you would have them do unto you.” ↩

- [14] Cf. Did. 1:2 (“The Way of Life, therefore, is this: First, you must love God, who made you; second, your neighbor as yourself: all you might wish not be done to you, you also must not do to another”). On the Golden Rule as an interpretation of the love command, see Flusser, “Jesus, His Ancestry, and the Commandment of Love,” 168-169; P. S. Alexander, “Jesus and the Golden Rule,” in Hillel and Jesus: Comparative Studies of Two Major Religious Leaders (ed. James H. Charlesworth and Loren L. Johns; Minneapolis: Fortress, 1997), 363-388, esp. 374-376; Huub van de Sandt and David Flusser, The Didache: Its Jewish Sources and its Place in Early Judaism and Christianity (CRINT III.5; Assen: Royal Van Gorcum; Minneapolis: Fortress, 2002), 158-160; Serge Ruzer, “‘Love Your Enemy’ Precept in the Sermon on the Mount in the Context of Early Jewish Exegesis: A New Perspective,” Revue Biblique 111.2 (2004): 193-208, esp. 197-198. ↩

- [15] Flusser suggested that the original thrust of Jesus’ critique is that some people interpreted the command as “Love your friend and hate your enemy,” the noun רֵעַ (rēa‘) being understood in the narrow sense of “friend” instead of the broader sense of “neighbor.” See David Flusser, “‘It Is Said to the Elders’: On the Interpretation of the So-called Antitheses in the Sermon on the Mount,” Jerusalem Perspective (2014) [https://www.jerusalemperspective.com/11496/], under the subheading “The Sadducees and the Abuse of Scripture.” Flusser believed Jesus reacted against the teachings of the Sadducees, but we think it is more likely Jesus was responding to those who sympathized with the views of militant Jewish nationalists such as the Fourth Philosophy. ↩

- [16] See David Flusser, “The Torah in the Sermon on the Mount,” Jerusalem Perspective (2022) [https://www.jerusalemperspective.com/27966/], courtesy of WholeStones.org [https://wholestones.org/the-torah-in-the-sermon-on-the-mount/], under the subheading “The Love Command: Friends, Neighbors, and Enemies.” ↩

- [17] Flusser, “‘It Is Said to the Elders’: On the Interpretation of the So-called Antitheses in the Sermon on the Mount,” under the subheading “The Sadducees and the Abuse of Scripture.” ↩

- [18] Luke’s version of the story describes the man as being παραλελυμένος (paralelūmenos; Luke 5:18), which could mean that the man was incapable of voluntary movement (i.e., paralyzed), but could also mean more generally that he was weakened from sickness and therefore unable to walk. The Markan and Matthean versions of the story are more explicit in referring to the man as a παραλυτικός (paralūtikos, “paralytic”; Matt. 9:2; Mark 2:3). Because the designation “paralyzed man” is most familiar, this is how we will refer to the sick man in the story, without, however, excluding the possibility that the man was merely bedridden and not paralyzed in the strict sense of the word. ↩

- [19] For this view, consult standard commentaries. ↩

Comments 2

I do not find some of the main points of this article to be convincing, because it does not handle the rhetorical crux of the story. The article’s account fails to explain why or how Jesus connects forgiveness with the healing and why he specifically asked: “Is it easier to say ‘Your sins are forgiven,’ or ‘Stand up and walk’?”

The article’s argument also hinges on a questionable reading of ὁ υἱὸς τοῦ ἀνθρώπου (the son of man), suggesting that it has generic reference, that it refers to any or every man: ‘people have authority to forgive’. That such a grammatically definite (arthrous) noun phrase in Greek can indeed have generic reference is clear in other contexts, such as Mat 8:20: ‘The-foxes (αἱ ἀλώπεκε) have dens’. But given how Jesus elsewhere in the Synoptics uses ὁ υἱὸς τοῦ ἀνθρώπου to refer to himself, including in Mat 8:20, Mat 10:23, etc. interpretating ὁ υἱὸς τοῦ ἀνθρώπου here in the story as ‘people’ (every or any person) is doubtful.

In my response here I don’t mean to detract from the many interesting points in this article about the two types of love and the fact that on other occasions in his ministry Jesus taught about the importance of people forgiving (and loving) each other and even their enemies. But this article fails to convince me that this is a point of the story.

Instead, I think it’s much more likely that this story assumes that there is a type of forgiveness that God alone can do, and that Jesus was teaching that he, in his role as the Son of Man, could do that. By healing the man, Jesus proves that he could also forgive, and by proving that he can forgive, he proves that he shares something unique with God. This analysis requires that we recognize that there are different senses of “forgive” or types of “forgiveness” in the Bible, something that our English vocabulary may obscure.

That there are different types of “forgiveness” is suggested by the range of Hebrew vocabulary, like nāsā’, kippēr, sālaħ/nislaħ and the different metaphors used to talk forgiveness (e.g., washing, covering, forgetting, and wiping away). And, just as importantly, there are clear patterns in Scripture for who can do what. I assume that such a nuanced understanding of forgiveness is what is behind the Pharisees’ assumption that God alone can truly forgive sins or fully undo their results.

One of the more common verbs for ‘forgive’ is nāsā’, which is based on the idea that sins can be ‘carried’ or ‘borne’. In Scripture this can be a way of talking about forgiveness as well as punishment. In a negative sense, a person who bears his own sins (or guilt for a sin) is bearing the corresponding punishment for the sin (EXO 28:43, LEV 5:1 etc.). In a positive sense, nāsā’ is used to refer to forgiveness in very generic terms. Both God and people can be the agent of nāsā’, but it is easy to imagine that there can be a difference. In Gen 50, the brothers tell Joseph that one of Jacob’s final requests is that Joseph forgives (nāsā’) his brothers. Joseph is asked to bear their faults, which we can interpret variously as to not hold their crime against them and/or to act as if they had never done it. But of course Joseph still knows what they did. And even though he ‘forgave’ them, they may have still felt guilty.

Similarly, in the New Testament we are commanded to ‘forgive’ one anothers’ sins; the idiom used in the NT is often ‘release’ (ἀφίημι) as when a debt is released. We can forgive another person’s sins in the sense of releasing that person’s debt and ceasing to require it to be paid back. But for humans that doesn’t necessarily erase what they have done before God (perhaps they are still guilty before God) nor does that make us forget what they have done.

But in the Bible God is able to forgive sins in a way that permanently erases the effects or record in a total way. To recognize this fact is simply to recognize that God can do things that people cannot do. The totality of forgiveness is alluded to by metaphors like ‘wiping away’ (PSA 51:3-4) or causing to disappear (JER 50:20) or when the all-knowing God paradoxically says he will never again remember the people’s sin/guilt (PSA 25:7). Nāsā’ as well can presumably refer to total forgiveness if God is the agent. But people, on their own, unless God share’s his authority and power, cannot cause or declare another person’s sins to be as if they never existed. We don’t have that power.

The qal verb sālaħ (and the corresponding nif’al form), in fact, explicitly refers to what God alone can do. In every occurrence in the Bible, God is the explicit or implicit agent of this verb; never is man the agent (a point underscored by Milgrom in his Leviticus commentary). The verb features especially in Leviticus in the context of kippēr (wiping out sin). So, for me, this appears to be what is behind the way the Pharisees’ accusation. Like the English verb ‘forgive’, so ἀφίημι is ambiguous (i.e., semantically ‘underspecified’). But if Jesus were speaking Hebrew and used sālaħ, or if by means of some other phrase Jesus referred to an absolute and complete type of forgiveness, the Pharisees could easily construe Jesus’ statement as a claim that he could forgive sins in a way that God alone could do. That Jesus can heal the man, instantly, there on the spot, supports his claim that the Son of Man can undo the effects of and erase the sins done by the man (sins that the man presumably did not commit against Jesus but against God or another). Sālaħ is in fact the very verb that Delitzsch used in his translation of this story in the Synoptics.

— Nicholas Bailey

Nicholas,

Thank you for your thoughtful engagement with this article. It is always gratifying to know that what I’ve written hasn’t simply evaporated into the ether.

Allow me to respond to your main critique that “this article fails to convince me that this [i.e., the importance of people forgiving ⟨and loving⟩ each other and even their enemies] is a point of the story” by responding to a few other failures you noted along the way.

“The article’s account,” you noted, “fails to explain why or how Jesus connects forgiveness with the healing.” True enough. That wasn’t the part of the story I was focused on. But the answer isn’t hard to find, even within the article itself. It’s part of that two-way relationship between a human being and God and that human being and his or her neighbor. To borrow an example cited in the article, Ben Sira insisted that in order for his readers to receive healing from God they had to forgive their neighbors. That’s when one needed healing for oneself. What about when a person wanted healing for someone else? We saw an example of that, too, in the case of Avimelech. In order for Avimelech to be healed it wasn’t just God who had to forgive him, Abraham had to forgive him, too. Only when he was forgiven from both sides could Avimelech be healed. I think the same thing was going on with Jesus and the paralyzed man. Jesus recognized that before God’s healing power could break through to him, the paralyzed man needed forgiveness from God and his neighbors.

The underlying idea was that sin was an obstacle to God’s healing power, but when sin is got out of the way healing can take place. Hanina ben Dosa claimed, “It isn’t the venomous reptile that kills, it’s sin that kills.” Without sin, death can’t get a grip on us. But where there is sin, death latches on. Jesus’ view seems to be similar. The fact that the man was paralyzed was proof enough that sin had given sickness and death a foothold in the paralyzed man’s life. Only with forgiveness could God’s healing power break through. But that forgiveness needed to come from two sides: from God and from human beings. Without it coming from both directions, forgiveness wasn’t complete, and sin still had a foothold. Hence, Jesus taught his disciples to pray, “Forgive us our debts as we forgive our debtors.” Human beings need to participate in and enact God’s forgiveness in order for the Kingdom of Heaven to be realized.

Another failure you noted is that “the article’s argument also hinges on a questionable reading of ὁ υἱὸς τοῦ ἀνθρώπου (the son of man), suggesting that it has generic reference.” In response, I would refer you to the conclusion of the story, where the onlookers praise God who “has given such authority to human beings” (Matt. 9:8). Which authority is that? To heal? Or to forgive? The story implies that both answers are correct. “But in order that you may know that the son of man has authority on earth to forgive sins, I say to you, Arise, take your mat and walk!” The people praised God for giving such authority to human beings, and the authority that Jesus demonstrated human beings can exercise is healing and forgiveness.

Also, from a rhetorical point of view, understanding Jesus’ use of “son of man” in an inclusive sense makes for a much stronger argument. Those who claimed that “no one can forgive sin except God alone” denied that human beings can forgive sins. Arguing that “No, human beings can also forgive sins” is more forceful (and, in my view, more persuasive) than arguing, “Yes, of course God can forgive sins and human beings can’t, but there’s one important exception you don’t know about: I, the Son of Man, can also forgive sins.” The first argument refutes the opposing view outright: “You’ve got it all wrong.” The second argument concedes everything but then magically pulls an exceptional rabbit out of the hat: “You’d be right, except for this one thing you couldn’t possibly have known about.”

And then there is also a logical problem. If Jesus wanted to prove that he could forgive sins, which is something that only God can do, then he ought to have done something else that only God can do. Instead, to prove that he (and other human beings) could forgive sins, Jesus did something that he and other human beings (namely his apostles) can also do: he healed the sick man.

You wrote: “People, on their own, unless God share’s his authority and power, cannot cause or declare another person’s sins to be as if they never existed. We don’t have that power.” But isn’t it precisely the point of the story that God has shared his authority to forgive sins and therefore we do have that awesome power and responsibility? “And they glorified God, who had given such authority to human beings” (Matt. 9:8). Can human beings forgive sins all on their own? No, of course not. We must do so in concert with God’s forgiveness. But the shocking implication of Jesus’ teaching is that God can’t forgive sins all on his own either. He needs our partnership in order to bring healing, forgiveness, and redemption into the world.

I find the conclusion that God needs our participation if we’re ever to experience redemption to be a far more compelling, challenging, and daunting lesson than the conclusion that Jesus is a special exception to the rule that “no one can forgive sins except God alone,” which doesn’t challenge me to do anything at all.