How to cite this article: Joshua N. Tilton, “Coordinating Ritual and Moral Purity in the New Testament,” Jerusalem Perspective (2025) [https://www.jerusalemperspective.com/30047/].

Updated: 4 April 2025

In his book, Impurity and Sin in Ancient Judaism,[1] Jonathan Klawans argued that it was disagreements over moral purity that played as great a role in distinguishing the Second Temple Jewish sects (Pharisees, Sadducees, Essenes, etc.) from one another as disagreements over ritual purity.[2] Although disagreements regarding ritual purity were undeniably divisive, the issue of moral purity and how it should (or should not) be coordinated with ritual purity determined how each sect related to its members and to the Jewish people as a whole. An extreme view that merged ritual and moral purity required separation from broader “sinful” Jewish society, while a more moderate view that separated ritual and moral purity allowed for full participation in broader Jewish society. At the end of his book Klawans analyzed three New Testament figures—John the Baptist, Jesus, and Paul—with respect to how they coordinated the concepts of ritual and moral purity, with a view to better understanding how these figures fit in with or stood apart from the other ancient Jewish sects.

In this essay we will attempt to refine Klawans’ analysis of these New Testament figures by introducing a small but consequential distinction regarding the communicability of moral impurity, which he seems to have left out of the discussion. We will also take each figure’s audience into the equation, because the audience each figure addressed determines what they said about the issues of ritual and moral purity every bit as much as their opinions regarding how the two concepts should be correlated. By taking these factors into account we may be better equipped to understand how John the Baptist, Jesus, and Paul coordinated the concepts of ritual and moral purity.

Ritual Versus Moral Purity

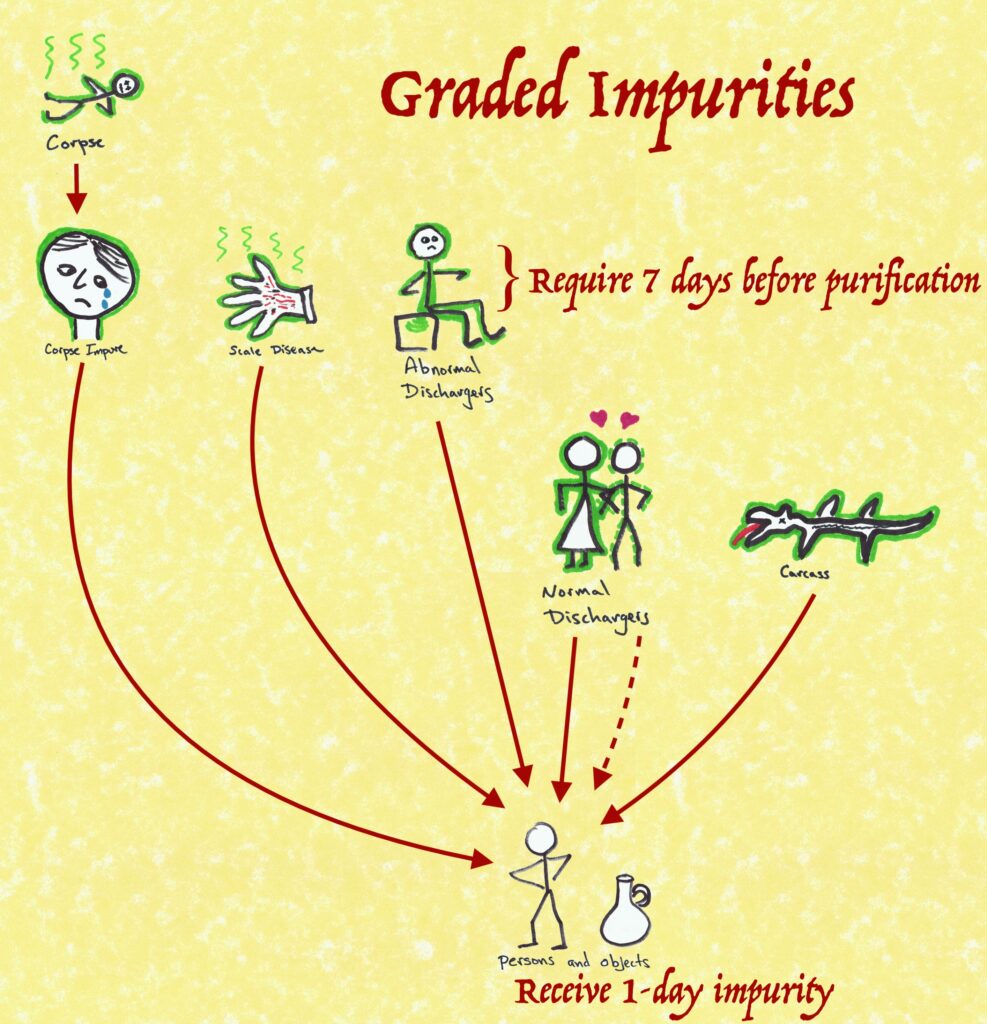

Two concepts of purity exist side by side in the Hebrew Scriptures.[3] Klawans referred to one concept as “ritual purity” and the other concept as “moral purity.”[4] The two types of purity have several distinguishing characteristics.[5] Ritual purity is particular to Israel, whereas moral purity is universal. Ritual purity is an organic part of the natural order and as such morally neutral, whereas moral purity requires the conscious decision of the individual and the exercise of will, with the result that it is morally charged, as the name implies. Ritual impurity is more or less involuntary, since it can be the result of bodily functions over which a person has no control. Moral impurity is voluntary, since a person can always chose not to commit the sins that make him or her morally impure. Since ritual defilement is inevitable ritual purity is temporary, but human beings have it within their power to restore it through purification rituals. Moral purity is permanent unless it is intentionally defiled, in which case defilement, too, is permanent, because it is not within a human being’s power to restore. Only an act of the divine will responding to a sinner’s repentance can restore a person to moral purity. The sources of ritual defilement (ritual impurity) are natural substances: the carcasses of certain animals, genital discharges, scale disease and the vapors arising therefrom, corpses and death vapor. The sources of moral defilement, on the other hand, are the commission of certain grave sins that cannot be undone: murder, idolatry and gross sexual transgressions being chief among them. Ritual impurity defiles the body and excludes the impure person from the Temple. Moral impurity defiles the spirit and cuts the sinner off from communion with God. Ritual impurity is contagious. Depending on the severity of the impurity, a person can transmit impurity to other persons and objects at a greater or lesser remove for longer or shorter periods of time. Moral impurity defiles the ground upon which it is committed and accumulates there until reaching a breaking point when God can no longer stand to reside in it and he abandons it. Ritual impurity is not punished unless one intentionally defiles holy places or holy things. Moral impurity is punished by exile and, ultimately, death.

An example of ritual impurity would be the burial of a corpse. Human corpses are the most severe source of ritual impurity. Contact with a corpse or even entering the same enclosed space as a corpse renders a person impure for seven days and requires special purification rituals in order for the impure person’s purity to be restored. Despite the requirement that a person impure from a corpse stay away from the Temple and from contact with holy things (sacrifices, tithes), the defiled person may still be in good moral standing with the broader Jewish community and with God. Burying a corpse was mandatory, the responsibility for which usually fell upon the next of kin, but burying an abandoned corpse was considered to be a great act of charity.

Murder is a prime example of moral impurity. Although Cain, not being under the Mosaic covenant, was not subject to the requirements of ritual purity, he was morally culpable for the murder of his brother Abel. Cain’s act of murder defiled the land as Abel’s blood cried out from the ground. In anger and disgust God turned his face away from Cain, and Cain’s soul bore the mark of impurity, and he was exiled from the land.

We read about another example of moral impurity in the book of Leviticus. There, speaking through Moses, the Lord warns Israel not to walk in the ways of Egypt or the Canaanites when they enter the land he is giving them (Lev. 18:3). He then enumerates various prohibited sexual relationships mostly having to do with incest, although other sexual practices are also proscribed. Then God warns:

Do not defile yourselves with any of these practices, for with all these practices the Gentiles whom I am driving out before you defiled themselves. And the land was defiled, and I visited its iniquity upon it, and the land puked up its inhabitants. So you must keep my statutes and my judgments and not do any of these abominations, neither the native born nor the sojourner who sojourns among you—for the people of the land who were before you did all these abominations and the land was defiled—and the land will not puke you up in your defilement of it, as the land puked up the Gentiles who were before you. For everyone who does any of these abominations, souls of those who do so will be cut off from among their people. So you must keep my proscription against doing any of the abominable practices that were done before you, and you must not be defiled by them. I am the Lord your God. (Lev. 18:24-30)

This passage in Leviticus not only highlights several of the distinguishing features of moral purity we have already mentioned (moral purity is required of Gentiles as well as Israelites, moral impurity defiles the soul and the land, its punishment is exile), it also calls attention to the fact that a special vocabulary is associated with moral purity: the taboo or abomination (תּוֹעֵבָה [tō‘ēvāh]), a cause of disgust and indignation. Typically, this term is used in reference either to foods that are considered vile (e.g., Gen. 43:32; Deut. 14:3) or of morally reprehensible acts (Lev. 18:26) or objects (idols; e.g., Deut. 27:15). “Abomination” is not a term Scripture typically uses for ritual defilement.

Another lexical item associated with moral purity is the Hebrew root ח‑נ‑פ (ḥ-n-p) connoting “pollute,” “pollution.” An example of this usage occurs in the book of Numbers:

You must not pollute the land that you are in, for blood pollutes the land, and the land cannot be atoned for the blood spilled on it except by the blood of the one who spilled it. (Num. 35:33)

Money is an interesting test case for the difference between ritual and moral purity. Coins are not susceptible to ritual impurity,[6] but “the wages of a dog and the hire of a prostitute” are not to be paid into the Temple treasury because this money was morally compromised (Deut. 23:18).[7]

Coordinating Ritual and Moral Purity in Second Temple Judaism

Although the concepts of ritual and moral purity remain fairly distinct in the Hebrew Scriptures, the similarities between the two concepts, the partial overlap of vocabulary (“pure” and “impure”), and the lack of any clear statement articulating the difference led to differing opinions regarding how the two concepts should be coordinated. Philo of Alexandria viewed ritual and moral purity as parallel and mutually reinforcing.[8] Ideally, one would maintain purity in body and soul. Ritual and moral purity are two aspect of human perfection, and the ritual observances of the one held spiritual lessons for the observance of the other:

The law would have such a person [i.e., a worshipper in the Temple—JP] pure in body and soul, the soul purged of its passions and distempers and infirmities and every viciousness of word and deed, the body of the defilements which commonly beset it. For each it [i.e., the Jewish law—JP] devised the purification which best befitted it. For the soul it used the animals which the worshipper is providing for sacrifice, for the body sprinklings and ablutions…. (Spec. Leg. 1:257-258; Loeb)

The rabbinic sages, and most likely the Pharisees before them, preferred to keep a distance between ritual and moral purity, rarely discussing the two in the same context. According to Klawans, one strategy the sages had for compartmentalizing the two concepts was to discuss ritual purity in halakhic contexts and to relegate moral purity to aggadic discussions.[9]

In aggadah the rabbinic sages were capable of using ritual purity as a metaphor for moral purity, as we see in the following homily:

If there was [the ritually defiling carcass of—JP] a creeping thing in a person’s hand, then even if he immersed in Siloam and in all the waters of creation, he cannot ever be made pure. But let him cast away [the carcass of—JP] the creeping thing from his hand, and immersion in forty seahs [of water in a mikveh—JP] suffices for him. For it is said, But the one who confesses and forsakes [his wicked deeds—JP] will receive mercy [Prov. 28:13], and it is said, Let us raise our hearts and our palms [to God in heaven] [Lam. 3:41]. (t. Ta‘an. 1:8)

In this homily ritual purity is used as an analogy for moral purity. Just as a person must separate from a source of ritual defilement in order to become ritually pure, so a person must separate from sin in order to become morally pure.

One place where moral purity does enter halakhic discussions in rabbinic sources concerns the duty to save human life. According to the sages, any commandment may be violated (such as resting on the Sabbath) in order to save a human life, except for the prohibitions against murder, idolatry and sexual transgression (t. Shab. 15:17), the very sins that result in moral impurity. It is better to die than to stain one’s soul with such heinous sins.

Unlike the Pharisees and rabbinic sages, who compartmentalized ritual and moral purity, the Qumran sectarians, who are probably to be identified with the Essenes or a subset thereof, tended to merge the concepts of ritual and moral purity.[10] The covenanters viewed ritual defilement as a moral failing, or at least resulting from morally compromising situations, and they regarded sins as ritually defiling to the degree that sinners could transmit ritual defilement to people who were ritually pure.

In the Dead Sea Scrolls the merging of ritual and moral purity is exemplified in crossover of vocabulary for ritual defilement, like נִדָּה (nidāh, “[menstrual] impurity”), into discussions about sin. It is also manifest in the treatment of sinful outsiders and transgressors of the sect’s code by insiders as ritually defiling. Members who transgressed were excluded from the pure meals that were eaten communally, while outsiders were not to be admitted to their purification rites until they had become full members of the sect. The merging of the two types of purity is especially evident in the covenanters’ understanding that ritual purification was not possible without repentance and that forgiveness of sin must be accompanied by ritual purification (cf. 1QS III, 5-6; V, 13-14).

Viewing sins and sinners as ritually defiling had profound social consequences for the Qumran covenanters. As Klawans observed, “If you believe in the maintenance of purity, and you believe that sin and sinners are defiling, you have little choice but to remove yourself from that society that you consider to be irredeemably sinful.”[11]

John the Baptist, Jesus, and Paul

In the penultimate chapter of his book Klawans analyzed three New Testament figures—John the Baptist, Jesus, and Paul—with respect to how they coordinated ritual and moral purity. Were these figures more like the Essenes, merging the concepts of ritual and moral purity? Or were they more like the Pharisees and their rabbinic heirs in compartmentalizing ritual and moral purity? Or did they fall somewhere in between?

John the Baptist

With regard to John the Baptist we have not only the New Testament but also Josephus’ testimony to inform us about how he correlated moral and ritual impurity. From the New Testament we learn that John the Baptist proclaimed an immersion of repentance for the release of sins (Mark 1:4; Luke 3:3). From Josephus we have the following statement:

…he [i.e., John the Baptist—JP] had exhorted the Jews to lead righteous lives, to practice justice towards their fellows and piety towards God, and so doing to join in baptism. In his view this was the necessary preliminary if baptism was to be acceptable to God. They must not employ it to gain pardon for whatever sins they committed, but as a purification of the body implying that the soul was already thoroughly cleansed by right behavior. (Ant. 18:117; Loeb [adapted])

Josephus would have us believe that John the Baptist correlated ritual and moral purity in much the same way as Philo of Alexandria. John called upon people to achieve moral purity through righteous living and to purify their bodies by immersing in water. Moral and ritual purity are parallel concepts that do not intersect: Josephus claimed John’s baptism could not gain pardon for sins—a proposition that stands in stark contrast to the Gospels’ testimony that John proclaimed an immersion of repentance for the forgiveness of sins.[12]

Klawans was suspicious of Josephus’ characterization of John’s message, and so are we. It appears to us that Josephus sanitized John’s message by (mis)representing the Baptist’s views on ritual and moral purity as being more compatible with Josephus’ own.[13] As Klawans argued, “Considering that the Gospels and Josephus both emphasize the importance of baptism to John, it is reasonable to assume that John did not consider repentance in itself to be sufficient for fully effecting atonement.”[14] What was lacking was the ritual of atonement John the Baptist proclaimed. In view of the nexus of sin, immersion, and forgiveness in John’s preaching, it is tempting to conclude that John the Baptist, like the Qumran covenanters, merged the concepts of ritual and moral purity. This conclusion would fit comfortably with Flusser’s characterization of John the Baptist as a semi-Essene, someone on the fringes of the Essene movement who had been influenced by their ideas but had broken through their doctrines of hatred for outsiders and double predestination into a universalism that embraced love for all humankind.

But Klawans did not draw this conclusion. Instead he doubts that John’s immersions were a purification ritual at all:

If John’s baptism were to be understood as purificatory, I would want to be able to point to explicit descriptions of the rite as purificatory, and I would want to be able to understand what kind of defilement—ritual or moral, bodily or otherwise—the rite is meant to purify.[15]

In two respects Klawans’ reservations are not quite fair, since 1) no ancient Jewish source ever explicitly states which kind of purity is in view, and 2) Josephus does state that John’s immersion was for the purity (ἁγνεία [hagneia]) of the body. Nevertheless, Klawans objects that “Josephus…does not state clearly what it is that John’s baptism purifies the body from.”[16] There are seemingly two options: either John’s immersion purified the body from normal ritual impurities (probably Josephus’ view) or his immersion purified the body from the physical stain of sin (likely the view Josephus wanted to suppress). Klawans correctly rejected the first option: “It is highly unlikely that his baptism served simply to purify individuals from the standard ritual defilements.”[17] Any immersion in living water or a mikveh could achieve that. But Klawans also rejects the second option: “It would be easier to understand John’s baptism as a ritual purification if it could be argued that he viewed sin as ritually defiling. Yet I know of no reason why we ought to assume that John held this view.”[18] The main reason for affirming that John did hold this view, one might argue, is that there are no other options left. If John’s immersion was not (solely) for purification from morally neutral impurities,[19] then it must have been for purification from the physical residue of sin.[20] But against this conclusion Klawans writes:

…there is no indication that either John or any of his followers behaved in a way to suggest that they considered sin or sinners to be ritually defiling. …Had John or his followers considered sin and sinners to be ritually defiling, and if the point of baptism was to remove such defilement, we would expect either that John and his followers would have kept physically apart from sinners, or that they would have frequently repeated baptism.[21]

Because he correctly notes that John was not a separatist like the Qumran covenanters, Klawans’ interpretation of John’s immersion veered off in another direction: “John’s personally administered baptism of atonement…was meant not to purify ritually individuals from sin or defilement, but to change the status of individuals once and for all.”[22] But if John’s baptism had nothing to do with purification, one wonders why he would have chosen a ritual, immersion, “a rite whose practice ancient Jews were more likely to associate with ritual purification.”[23] Would not the mode only have confused the message? Rather, immersion implies purification, and it remains to be understood what kind of purification John’s immersion was able to impart.

We believe the point at which Klawans’ argument breaks down is his conflation of the defiling force of sin with the defiling force of sinners. The Qumran covenanters believed both sin and sinners were sources of ritual defilement, the removal of which required immersion. But what if the Baptist had a more moderate view, regarding sin as ritually defiling, but not regarding sinners as such? After all, not every ritually impure person carried an impurity potent enough to transmit their impurity to others. A person who had become ritually defiled by a corpse could transmit a reduced impurity to the people with whom he or she came into contact. But a person who was ritually impure from having marital relations did not transfer impurity to other people through contact. Perhaps, therefore, John the Baptist agreed with the Essenes that the physical residue of sin needed to be washed away in order for the people of Israel to be ready for the eschaton, but unlike the Essenes, who withdrew from society because they thought sinners were ritually defiling, John the Baptist could allow those who received his immersion to reintegrate into society because contact with sinners would not make them impure. In other words, John the Baptist may have merged ritual and moral purity, but escaped the separatist consequences of this homogenization because he did not believe that sin residue was transmissible.

For Klawans, the eschatological significance of John’s immersion explains why his baptism, unlike oft-repeated ritual immersions, was a once-for-all event.[24] John’s immersion symbolized a rebirth of sorts, a permanent change of status. But another explanation seems more likely. John the Baptist expected the repentance he required of immersion candidates to mark a permanent change of lifestyle. While the recipients would undoubtedly continue to contract everyday ritual defilements, they were expected to cease defiling their bodies with sin. Regular immersions would therefore continue, but repeat immersions for sin impurity would be unnecessary. Thus, what made the Baptist’s immersion unique from everyday ritual immersions was this: whereas everyday immersions removed normal impurities, only the immersion John administered had the capacity to remove the physical residue of sin.[25]

The following tables illustrate the options available for differing views of the defiling force of ritual and moral purity:

|

Ritual Impurity |

|||

|

Spiritual Defilement |

Physical Defilement |

Contagious |

|

|

Pharisees/Rabbis |

✕ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

John the Baptist |

?✕? |

✓ |

✓ |

|

Qumran Sect/Essenes |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

.

|

Moral Impurity |

|||

|

Spiritual Defilement |

Physical Defilement |

Contagious |

|

|

Pharisees/Rabbis |

✓ |

✕ |

✕ |

|

John the Baptist |

✓ |

✓ |

✕ |

|

Qumran Sect/Essenes |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

The table above illustrates the Pharisaic/rabbinic compartmentalization of ritual and moral purity. For them, the two types of purity do not share any characteristics. Moral impurity is spiritually defiling, but it does not defile the body and is therefore not communicable. Ritual purity does defile the body and is contagious, but it is morally neutral and leaves no mark on the soul. The table above also illustrates the complete merging of ritual and moral purity we observe in the Dead Sea Scrolls. For the sectarians, moral impurity defiles spirit and body, and therefore sinners have the capacity to ritually defile those with whom they associate. Ritual impurity, meanwhile, is accompanied by spiritual defilement, and therefore ritual impurity requires repentance as well as ritual immersion. As for John the Baptist, the picture is somewhat murky, since his views can only be inferred from his behavior. The Baptist’s requirement that sinners must immerse as well as repent implies that sin defiled not only their spirits but also their bodies. That the Baptist did not require spiritually pure persons to separate from sinful society implies that John did not believe sinners could communicate their sin-generated impurity to others. Klawans did not consider the option that moral defilement could be physical but not contagious, and therefore concluded that John’s immersion did not purify the people who received his baptism.

A second reason Klawans believed John’s immersion was not for purification is that the sources are silent with respect to John’s views on ritual purity:

Another argument against viewing John’s baptism as a ritual purification is that none of the sources indicate that he had any particular concerns with ritual defilement. …Without such concerns, it is difficult to comprehend why John would advocate a distinctive rite of ritual purification.[26]

But this argument from silence is not convincing. If the special function of John’s immersion was that it was uniquely able to remove the physical stain of sin-generated impurity, then it is not surprising that he did not concern himself with purification from everyday ritual impurities. Regular immersions were already able to do that. We do not know whether John was lenient or strict with regard to ritual purity, but either way, the normal means of purification could wash away regular impurities. Sin-generated impurity, on the other hand, was stickier stuff and needed a stronger detergent. This is what John’s immersion supplied.[27]

With respect to whether the Baptist believed ritual impurities brought with them a moral stain, we are in doubt, which is indicated by the question marks in the table above. We think it is unlikely that he did so, for otherwise we might suppose his immersion would have to be repeated every time a person became ritually defiled. But it is possible that for purification from normal ritual impurities John believed regular immersion combined with repentance would suffice.

Jesus

Klawans’ analysis of how Jesus coordinated ritual and moral purity rests mainly on the handwashing controversy described in Mark 7 and Matthew 15. According to Klawans, Jesus did not merge ritual and moral purity, as did the members of the Qumran sect, but neither did he compartmentalize ritual and moral purity like the rabbinic sages and the Pharisees before them. Instead, Jesus prioritized moral purity over ritual purity: “Jesus…suggests that his followers would be better off if more attention were paid to what comes out of the mouth than what comes in.”[28] Eating with unpurified hands ran the risk of eating ritually impure food, potentially transferring impurity from the hands to the food and from the food to the rest of the body. Jesus does not appear to have taken this to be a serious threat. If a person became impure, they could always purify themselves. But if a person made themselves morally impure, how could they become pure? Klawans notes the “correspondence between what Jesus views as defiling and the sins that were generally conceived by ancient Jews as sources of moral defilement,”[29] and concludes that the controversy depicts “Jesus as emphasizing the morally defiling force of what Jews living in the land of Israel in the first century ce commonly believed to be morally defiling sins.”[30]

Thus far we agree. In broad terms Jesus would probably not have quarreled with the Pharisees about the distinction between ritual and moral purity:

|

Ritual Impurity |

|||

|

Spiritual Defilement |

Physical Defilement |

Contagious |

|

|

Pharisees/Rabbis |

✕ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

Jesus |

✕ |

✓ |

✓ |

.

|

Moral Impurity |

|||

|

Spiritual Defilement |

Physical Defilement |

Contagious |

|

|

Pharisees/Rabbis |

✓ |

✕ |

✕ |

|

Jesus |

✓ |

?✕? |

✕ |

The one point where Jesus might have disagreed with the Pharisees with regard to moral impurity is whether sin left a physical stain on the body. Like the Pharisees and, as we have argued, like John the Baptist, Jesus did not view sinners as ritually defiling. But the fact that Jesus participated in John’s immersion may indicate that, like John but unlike the Pharisees, Jesus was willing to entertain the notion that sin left a physical residue that needed to be washed away. But it is also possible that Jesus filtered John’s message through his own presuppositions and, like Josephus, reinterpreted John’s immersion as a ritual purification of the body from normal ritual impurities that paralleled the inner purification of the soul through repentance.

What Klawans found distinctive about Jesus was “the fact that Jesus did not defend even the symbolic value of ritual purity laws, while he placed them in a position subordinate to other laws….”[31] In this regard Klawans sees Jesus as distinct from Philo, who saw ritual and moral purity as parallel but mutually edifying and reinforcing: “Philo’s prioritization of moral purity over ritual purity still provides a symbolic justification for the lesser partner of his pair, whereas Jesus’s teachings on the subject do not.”[32] But does not this difference between Jesus and Philo say more about their respective audiences than about their personal views? Jesus’ sparring partners in the dispute about handwashing were Pharisees, who did not have to be convinced of the importance of ritual purity. They were not in danger of misunderstanding Jesus as implying that ritual purity need not be observed. But Philo addressed two audiences that did deny the value and necessity of ritual purity. On the one hand, Philo contended with the extreme allegorizers, who felt that so long as they took to heart the moral lessons the commandments were intended to teach, the actual observances could be dispensed with. On the other hand, Philo wrote with a view to non-Jewish Greek speakers, who were inclined to view Jewish customs as silly superstitions. Philo had to defend the “special laws” as conveying moral lessons to their observers. Practicing the observances yielded virtuous fruits. Hence, no conclusions should be drawn from Jesus’ failure to defend practices his audience did not question. Nevertheless, Klawans is undoubtedly correct that the absence of a defense of ritual purity in Jesus’ teachings likely “played a role in allowing early Christianity to move in the direction that it ultimately did.”[33] It was easier for Gentile Christians to deny the validity of ritual purity when there were no direct statements from Jesus to contradict them.

Had Klawans broadened his discussion beyond what Jesus said (or failed to say) about ritual purity, and considered stories about Jesus’ deeds in relation to ritual purity, he might have arrived at a more balanced assessment of the value Jesus placed on ritual purity. The story of the centurion’s slave (Matt. 8:5-13 ∥ Luke 7:2-10) portrays Jesus as willing to ritually defile himself by entering a Gentile’s home in order to save the life of a centurion’s slave. This willingness hints at the higher value Jesus placed on morality than on ritual purity. But the specific argument that convinced Jesus to go to the centurion’s home—that the centurion was morally worthy (ἄξιος [axios]; Luke 7:4) despite being ritually unfit (ἱκανός [hikanos]; Matt. 8:8 ∥ Luke 7:6)—is a two-sided coin. On the one side, it offers a practical example of Jesus’ prioritization of moral purity over ritual purity. The centurion’s moral excellence trumped Jesus’ need to maintain his ritual purity.[34] But on the other side of the coin, the fact that Jesus needed a valid argument to convince him to temporarily forfeit his ritually pure status is a testament to the real value Jesus placed on ritual purity.[35]

Paul

In his analysis of Paul, Klawans notes that the Pauline Epistles are replete with purity imagery and vocabulary:

[Paul] expresses his concerns with defilement throughout his letters, and certainly his community was expected to maintain some standard of purity. But what were Paul’s specific concerns? He does not appear to be concerned with ritual impurity at all.[36]

In answer to his question, Klawans observes that when Paul refers to the avoidance of impurity he does so in connection with sexual sins and idolatrous practices and concludes that Paul’s “concern is for his followers to maintain moral purity by shunning the sinful behavior which, according to the Hebrew Bible and ancient Jewish literature, was perceived to be morally defiling.”[37] Klawans also ruled out the possibility that Paul merged the concepts of ritual and moral purity because “[i]f Paul had been concerned with the ritually defiling force of sins, we would expect to see frequently repeated rituals of purification being performed upon casual contact with sinful outsiders, but we see nothing of the sort.”[38] In this respect Paul would have agreed with the Pharisees and disagreed with the Qumran sectarians about the ritually defiling force of sin, an attitude that is hardly surprising given Paul’s Pharisaic background.

So we may represent the manner in which Paul coordinated ritual and moral purity as follows:

|

Ritual Impurity |

|||

|

Spiritual Defilement |

Physical Defilement |

Contagious |

|

|

Paul |

✕ |

?✓? |

?✓? |

.

|

Moral Impurity |

|||

|

Spiritual Defilement |

Physical Defilement |

Contagious |

|

|

Paul |

✓ |

✕ |

✕ |

Klawans sees Paul as similar to John the Baptist with regard to baptism. Like John’s immersion, “the purity achieved by Paul’s baptism is of the moral, not ritual sort.”[39] Klawans also sees Paul carrying on the legacy of Jesus, but to more radical conclusions. Whereas Jesus prioritized moral purity over ritual purity, he regards Paul as rejecting ritual purity altogether:

Jesus prioritized the maintenance of moral purity over the maintenance of ritual purity. Paul would seem to have taken the next step: …he does not articulate any interest in issues relating to ritual purity. So with Paul we see a break with the past, in his rejection of the need to maintain ritual purity.[40]

Although Klawans regarded Paul’s lack of concern for ritual purity as a break from his Jewish past, we think the lack of concern for ritual purity in Paul’s letters is simply a reflection of Paul’s audience. Paul regarded himself as the pagans’ apostle. It was his mission to win the Gentiles for Christ. And for Gentiles, issues of ritual purity and impurity simply did not apply. Therefore, we should not expect to find instructions about observing ritual purity in Paul’s letters, since the epistles are addressed to his congregations consisting mainly or exclusively of Gentile believers.[41]

Paul wrote his letters as a Jewish follower of Jesus to non-Jewish followers of Jesus who wished to live lives pleasing to Israel’s God. Since observing ritual purity was not how non-Jewish believers could please God, Paul did not bore his readers with irrelevant details about ritual purity. But living lives of moral purity was a way for non-Jewish believers to please God, so in his letters Paul discussed this topic extensively. Therefore, from his failure to urge his readers to remain ritually pure no inferences about the value (or lack of value) Paul placed on ritual purity should be drawn.[42]

As for Paul’s similarity to John the Baptist, we cannot quite agree. Above we concluded that John the Baptist thought his immersion ritually purified (Jewish) sinners from the physical residue of sin. Not being subject to ritual impurity, Gentiles did not need ritual purification, not even from the physical residue of sin. But Gentiles, being both subject to the demands of moral purity and lawless, had stained their spirits with moral corruption, and therefore Paul believed his Gentile followers did need moral purification, which Christian baptism supplied. So agree with Klawans that Paul viewed Christian baptism as a moral purification of Gentile believers from spiritual, but not physical, impurity.

Since Paul’s letters omit discussion of ritual purity, we cannot be certain whether Paul agreed with all other first-century Jews that ritual purity physically defiled the body or that this physical defilement was transmissible. This uncertainty is indicated by question marks in the table above. Nevertheless, it is reasonable to suppose that Paul did accept these basic Jewish principles, but simply had no occasion to discuss them.

Conclusion

We agree with Klawans’ basic premise that differing methods of coordinating ritual and moral purity played a significant role in dividing the various Second Temple Jewish sects from one another. We also agree that determining how John the Baptist, Jesus, and Paul coordinated ritual and moral purity can help us understand where these central New Testament figures fit in the variegated landscape of Second Temple Judaism. Klawans’ analysis of these figures, however, did not sufficiently consider all the different ways in which ritual and moral purity could be coordinated. He also failed to give due consideration to the different audiences these central figures addressed. These failures led to slightly distorted conclusions about John the Baptist, Jesus, and Paul.

|

Ritual Impurity |

|||

|

Spiritual Defilement |

Physical Defilement |

Contagious |

|

|

Pharisees/Rabbis |

✕ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

Jesus |

✕ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

Paul |

✕ |

?✓? |

?✓? |

|

John the Baptist |

?✕? |

✓ |

✓ |

|

Qumran Sect/Essenes |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

.

|

Moral Impurity |

|||

|

Spiritual Defilement |

Physical Defilement |

Contagious |

|

|

Pharisees/Rabbis |

✓ |

✕ |

✕ |

|

Jesus |

✓ |

?✕? |

✕ |

|

Paul |

✓ |

✕ |

✕ |

|

John the Baptist |

✓ |

✓ |

✕ |

|

Qumran Sect/Essenes |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

- [1] Jonathan Klawans, Impurity and Sin in Ancient Judaism (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000). ↩

- [2] Ibid., viii. ↩

- [3] Indeed, a third type of purity also appears in the Hebrew Scriptures, that of animals which are pure for consumption, but we will leave this third type of purity aside in the present discussion. ↩

- [4] Not all scholars agree as to the best terminology to describe these two systems of purity or even that these two systems of purity were entirely distinct. Kazen preferred to speak about “inner” and “outer” purity in place of “moral” and “ritual” purity, and argued that “outer” purity is not without moral components. See Thomas Kazen, Jesus and Purity Halakhah: Was Jesus Indifferent to Impurity? (rev. ed.; Winona Lake, Ind.: Eisenbrauns, 2010), 219-222. In this essay we will adopt Klawans’ categories since it is Klawans’ analysis we are considering. ↩

- [5] For an introduction to ritual purity, see Joshua N. Tilton, “A Goy’s Guide to Ritual Purity,” Jerusalem Perspective (2014) [https://www.jerusalemperspective.com/12102/]. ↩

- [6] Cf. m. Kel. 12:7. ↩

- [7] The Talmud attributes to Jesus the opinion that hire of a prostitute may be used to build a latrine (b. Avod. Zar. 17a). On this saying and the contexts in which it appears, see Joshua Schwartz and Peter J. Tomson, “When Rabbi Eliezer Was Arrested For Heresy,” Jewish Studies, an Internet Journal 10 (2012): 145-181. ↩

- [8] See Klawans, Impurity and Sin in Ancient Judaism, 64-66. ↩

- [9] Ibid., 92-117. ↩

- [10] Ibid., 67-91. ↩

- [11] Ibid., 90. ↩

- [12] Cf. Kazen, Jesus and Purity Halakhah, 233. ↩

- [13] See David N. Bivin and Joshua N. Tilton, “A Voice Crying,” The Life of Yeshua: A Suggested Reconstruction (Jerusalem Perspective, 2020) [https://www.jerusalemperspective.com/19636/], Comment to L35. ↩

- [14] Klawans, Impurity and Sin in Ancient Judaism, 139. ↩

- [15] Ibid., 140. ↩

- [16] Ibid. ↩

- [17] Ibid. ↩

- [18] Ibid., 141. ↩

- [19] We see no reason to deny that John’s immersion was also capable of removing normal ritual impurities. ↩

- [20] For a similar view, see R. Steven Notley, “John’s Baptism of Repentance,” Jerusalem Perspective (2004) [https://www.jerusalemperspective.com/6137/]. Notley, however, assumed that Josephus’ characterization of John’s baptism is basically correct. John’s immersion purifies outwardly, while the Holy Spirit purifies inwardly on account of repentance. We, by contrast, suppose that John agreed with the Essenes that sin ritually defiled the body outwardly and defiled the spirit inwardly. For John, the body and the spirit had to be purified from sin. ↩

- [21] See Klawans, Impurity and Sin in Ancient Judaism, 141. ↩

- [22] Ibid., 142. ↩

- [23] Ibid., 143. ↩

- [24] Ibid., 142. The sources do not state that John’s immersion was a one-time deal, but the necessity of having John the Baptist administer the immersion and the impracticality of frequent excursions to the desert to meet John lead to this conclusion. See Kazen, Jesus and Purity Halakhah, 236. Cf. Klawans, Impurity and Sin in Ancient Judaism, 139, 209 n. 24. ↩

- [25] We do not know what it was about John’s immersion that made it uniquely able to wash out the stain of sin. Did the Baptist believe that the Spirit of God hovered over the waters in which he immersed the repentant sinners? Cf. 1QS III, 7. ↩

- [26] Klawans, Impurity and Sin in Ancient Judaism, 140-141. ↩

- [27] However, we would not say with Kazen (Jesus and Purity Halakhah, 239) that John’s ritual immersion “concerned inner impurity only.” John’s immersion was more, but not less, than an ordinary immersion. The recipients emerging from John’s immersion would have been both ritually and morally pure in body and spirit, inwardly and outwardly. ↩

- [28] Klawans, Impurity and Sin in Ancient Judaism, 147. ↩

- [29] Ibid., 148. ↩

- [30] Ibid., 149. ↩

- [31] Ibid., 149. ↩

- [32] Ibid. ↩

- [33] Ibid. ↩

- [34] On purity implications of the centurion’s slave story, see JP Staff Writer, “Two Neglected Aspects of the Centurion’s Slave Pericope,” Jerusalem Perspective (2024) [https://www.jerusalemperspective.com/28673/], esp. under the subheading “The Centurion’s Moral Worthiness and his Ritual Status.” ↩

- [35] See JP Staff Writer, “What’s Wrong with Contagious Purity? Debunking the Myth that Jesus Never Became Ritually Impure,” Jerusalem Perspective (2024) [https://www.jerusalemperspective.com/29371/], esp. under the subheading “Did Jesus Not Care About Defilement?” ↩

- [36] Klawans, Impurity and Sin in Ancient Judaism, 151. ↩

- [37] Ibid., 152. ↩

- [38] Ibid., 154. ↩

- [39] Ibid. ↩

- [40] Ibid., 156. ↩

- [41] See Peter J. Tomson, “‘Devotional Purity’ and Other Ancient Jewish Purity Systems,” in his Studies on Jews and Christians in the First and Second Centuries (Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2019), 107-139, esp. 133. ↩

- [42] For further discussion of this topic, see Paula Fredriksen, “Judaizing the Nations: The Ritual Demands of Paul’s Gospel,” in Paul’s Jewish Matrix (ed. Thomas G. Casey and Justin Taylor; Rome: Gregorian & Biblical Press, 2011), 327-354. ↩