“And he entered the temple and began to drive out those who sold.” (Luke 19:45; RSV)

Based on archaeological excavations near the southern wall of the temple, the research of Shmuel Safrai, and a nuance of the Hebrew verb that is one of the equivalents for Greek ἐκβάλλειν (ekballein; drive out, banish; throw out; throw away, reject; cast out of a place, expel; remove, get rid of; put out), it may be necessary to reinterpret the gospel accounts of Jesus’ “cleansing” of the temple (Matt. 21:12-13; Mark 11:15-17; Luke 19:45-46; John 2:13-16), even suggesting a different location for Jesus’ action.

On the face of it, εἰσελθεῖν εἰς τὸ ἱερόν (eiselthein eis to hieron; Matt. 21:12; Mark 11:15; Luke 19:45) should mean “enter [one of the courts of] the temple,” perhaps the outer court, the Court of the Gentiles. However, since monetary transactions and other commercial activities were not permitted in the temple—not even in the Court of the Gentiles, into which non-Jews were allowed to go—in this context, “temple” probably refers to the area surrounding the temple platform, particularly the area immediately south of the Huldah Gates, those monumental gates that served as the entrance and exit for temple pilgrims. In rabbinic sources this area, or even the whole of Jerusalem, could be called “the temple.”[1] True, the Greek ekballein can mean “drive out”; but assuming the vendors and money changers conducted their business outside the temple, “drive out” is puzzling.

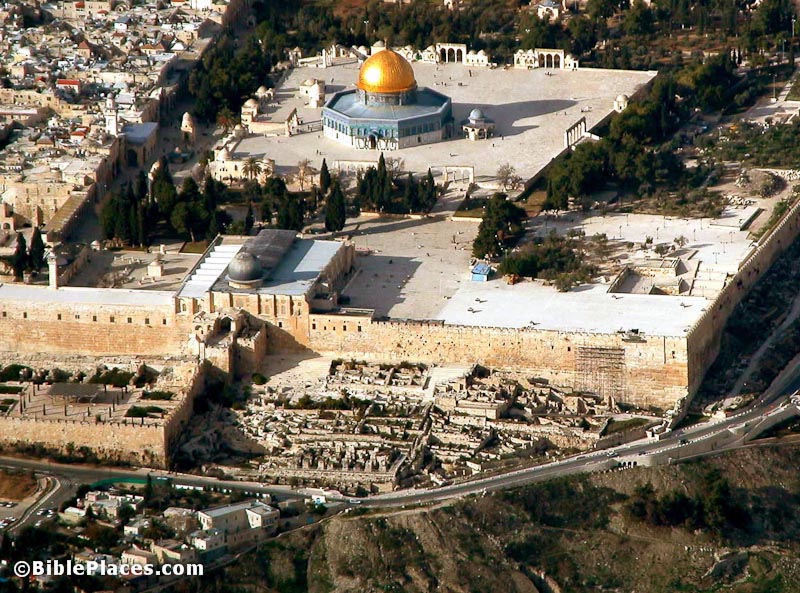

In this aerial view of the temple mount from the south, almost the whole of the mount’s southern support wall is visible. South of this ancient retaining wall excavations were conducted beginning in 1968. In these excavations, archaeologist discovered scores of mikva’ot. Photograph by Todd Bolen. Photo © BiblePlaces.com

Although not the most common Hebrew equivalent for ekballein, Robert L. Lindsey suggested that the Hebrew verb הוֹצִיא (hotsi; take out, bring out) underlies ekballein. If so, then ekballein might not imply violence, but only have the sense “take aside” or “pull off to the side”: Inviting the temple merchants out of their shops, Jesus took them aside (or, took them out of the area) to rebuke them. Jesus may not have used force, but rather castigated the sellers by skillfully combining texts of Scripture: “‘My house is a house of prayer’ [Isa 56:7], but you have turned it into ‘a den of thieves’ [Jer. 7:11].”

Paid Content

Premium Members and Friends of JP must be logged in to access this content: Login

If you do not have a paid subscription, please consider registering as a Premium Member starting at $10/month (paid monthly) or only $5/month (paid annually): Register

One Time Purchase Rather Than Membership

Rather than purchasing a membership subscription, you may purchase access to this single page for $1.99 USD. To purchase access we strongly encourage users to first register for a free account with JP (Register), which will make the process of accessing your purchase much simpler. Once you have registered you may login and purchase access to this page at this link:

- [1] The “temple” was not only the temple proper; but also the temple complex, including its commercial areas. Even Jerusalem is sometimes called “the temple” in Jewish sources: “As time passed, the Rabbis taught that the sanctity of the temple applied, in great degree, to the entire city of Jerusalem” (Shmuel Safrai, “Early Testimonies in the New Testament of Laws and Practices Relating to Pilgrimage and Passover”: 8-9 [forthcoming]). ↩

Comments 1

The irony of the reality of priestly corruption (Sadducees who believed only in money) was that it was facilitated by and dependent on the Pharisee’s scruples of law-keeping, including the tithe. The high priests were raking in close to 10% of the Israeli GDP solely due to the widespread zeal for the law, taught and enforced by the Pharisees. And this after a long era – 500 years – in which the temple had been entirely devoid of both the Ark of the Covenant and God’s presence dwelling between the non-existent cherubim. This was an open secret in Israel, certainly since Pompeii entered the Holy of Holies and came out saying “Wait a minute, this place is completely empty”. The rituals of Yom Kippur had been a farcical exercise in charades, with the so-called High Priest entering and exiting a Holy of Holies that was totally empty, pretending to do something extremely important (it was, but only in sustaining his family business). And then one day the Parochet was torn from top to bottom, finally exposing for all to see the emptiness and futility of the whole exercise. Not for nothing did Jesus himself refer to the temple only as a “house of prayer for all people”, and not a focus of divinely-appointed sacrifice. From God’s and Jesus’ point of view, the real business at the temple was being conducted by godly people in its various courts, as the book of Act abundantly shows.