Response revised: 4-Apr-2012

Question received from Joel R. Kemp (Pensacola, Florida, U.S.A.) that was published in the “Readers’ Perspective” column of Jerusalem Perspective 35 (Nov.-Dec. 1991): 2.

Question received from Joel R. Kemp (Pensacola, Florida, U.S.A.) that was published in the “Readers’ Perspective” column of Jerusalem Perspective 35 (Nov.-Dec. 1991): 2.

In the November-December 1990 issue [of Jerusalem Perspective] on page 14, David Bivin incorrectly quoted Luke 16:19-31 using the word “Gehenna.” This word is not found either in my Greek text, or my Hebrew New Testament in these verses. I realize that this was not the subject under consideration, but the statement reflects the general religious opinion in our time due to taking figurative writings literally.

David Bivin responds:

I’m delighted that our readers pay such close attention to the words of JP authors, particularly since I devoted several days of research to reach a decision about how to translate the Greek word in question. Here’s my statement from JP 29 containing the word “Gehenna”: “In the parable about Lazarus (Luke 16:19-31), the rich man begs Abraham to send Lazarus to warn the rich man’s brothers so that they won’t also end up in Gehenna.”[1]

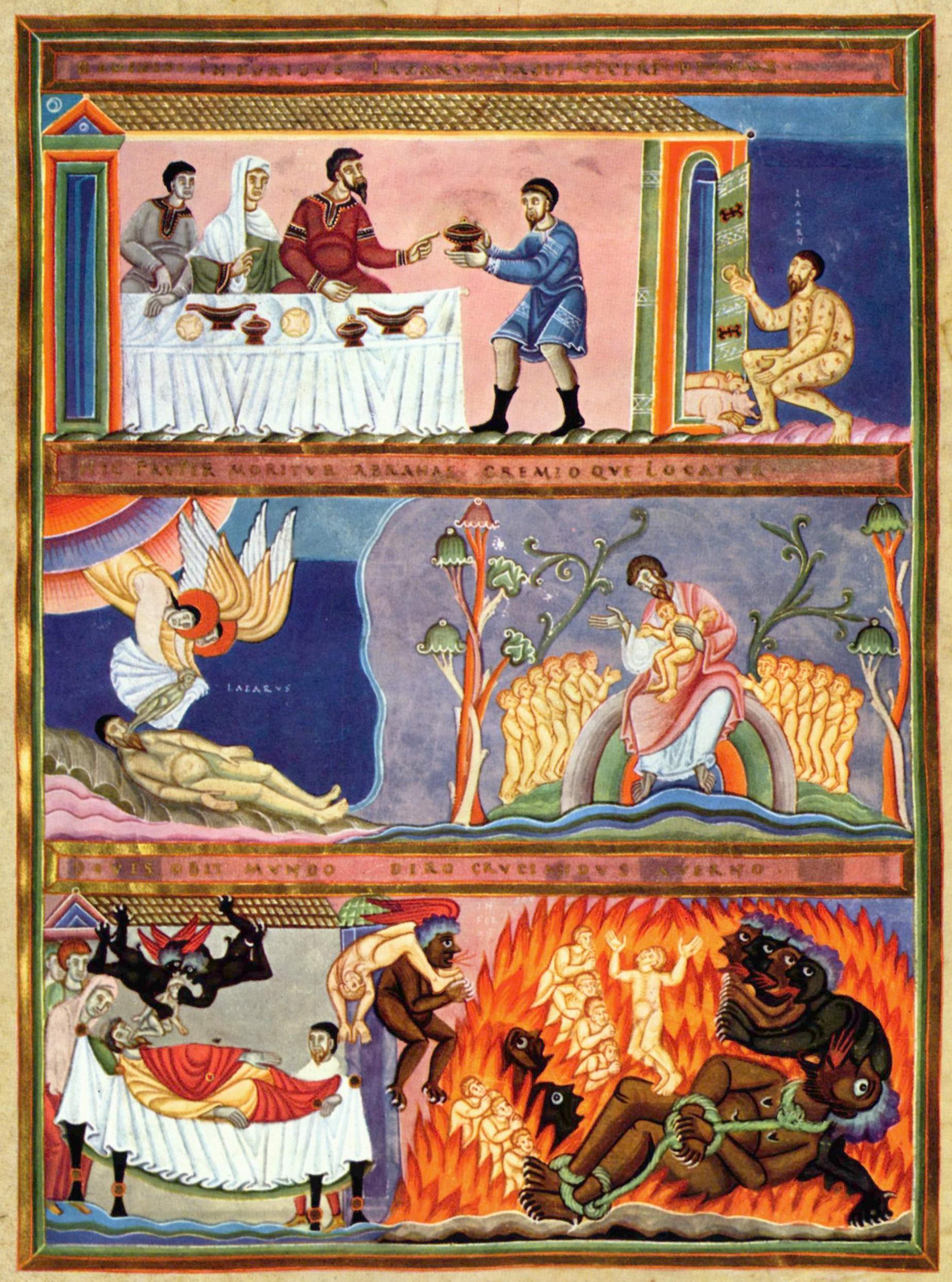

The parable of the Rich Man and Lazarus as illustrated in Codex Aureus Epternacensis. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

The reader is correct. The Greek text of Luke 16:23 reads ἐν τῷ ᾅδῃ (en tō hadē, “in Hades”). There appears to be no “Gehenna.” However, in this context ᾅδης (hadēs, “Hades”) is not equivalent to the Hebrew שְׁאוֹל (sheōl, the grave; death), but rather to גֵּיהִנּוֹם (gēhinōm, “Gehenna,” or “hell”), a meaning which hades also can have (see Joachim Jeremias, “ᾅδης” in Theological Dictionary of the New Testament [Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1964], 1:146-149).

It seems clear that the rich man was not sleeping in the grave, but rather was in torment (vs. 23) in a place of fire (vs. 24), what today we often refer to as “hell.” For that reason the New International Version translates, “In hell, where he was in torment.”

It is true that both the Delitzsch Hebrew translation (1877) and that of the Israel Bible Society (1976ff.) render hades with its standard Septuagintal equivalent, שְׁאוֹל (she’ōl), but I think that may be a mistake. In the Septuagint, hades is normally the translation of שְׁאוֹל (she’ōl) (61 times). Not surprisingly, it is never the translation of גֵּיהִנּוֹם (gēhinōm), since it is a post-biblical Hebrew word that does not appear in the Hebrew Scriptures. The Greek transliteration γέεννα (ge-enna), apparently representing the Hebrew gehinom, is used 11 times in the Synoptic Gospels and once in James (Jas. 3:6).

Many of the later, Second Temple-period Hebrew vocabulary items such as gehinom, along with many of the additional nuances that some biblical Hebrew words came to have in that period, are not found in the Hebrew Scriptures and consequently have no Septuagintal equivalents. Therefore, mechanically reconstructing to Hebrew Greek texts found in Matthew, Mark and Luke on the basis of Septuagintal equivalents can widely miss the mark. Here the context demands “Gehenna.”

Notes

- See David N. Bivin, “Hebrew Nuggets, Lesson 26: ta·NAK (Part 2),” under the subheading, “Two-fold Division.”[↩]

Comments 1

I disagree with Bivin’s conclusion. According to rabbinic literature persons are consigned to Gehinom at the final judgment following the resurrection. Since Jesus’ parable clearly presupposes that the resurrection has not happened yet, Lazarus’ neighbor could not have been in Gehinom. While it is true that the rich man’s misery in Hades does not match descriptions of Sheol in the Hebrew Scriptures, we must allow for the development of ideas concerning the afterlife during the Second Temple Period. My interpretation of the parable is that both Lazarus and his rich neighbor are in Sheol=Hades awaiting the final judgment. Nevertheless, they are held in different “waiting rooms” assigned to them as a preliminary judgment until the resurrection when body and soul will be reunited to receive the final verdict.