The term “genius” readily appears on the lips of scholars at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem when they refer to their former colleague, David Flusser (1917-2000). This word, which was understandably mixed with more critical words, was shared with me repeatedly the years I was Lady Davis Professor in the Hebrew University.

David Flusser was born in Vienna, Austria, in 1917. He moved with his parents to Prague, Czechoslovakia, in 1918. Growing up in that picturesque city, he studied classical philology until he immigrated to Jerusalem in 1939. At the Hebrew University he continued his studies in classics and also began to master Jewish history. In 1957 he earned the Ph.D. from the Hebrew University and was invited to teach in the Department of Comparative Religions, focusing upon Early Judaism (250 B.C.E. to 200 C.E.), Early Christianity, and Greek religion. He was elected to the Israel Academy of Sciences and Humanities and in 1980 received the Israel Prize.

Professor Flusser’s life was devoted to a study of Judaism and the origins of Christianity. His Jesus (New York: Herder and Herder, 1969) showed how he had mastered not only the classics, but also the Jewish apocryphal literature, Rabbinics, the New Testament, and related documents. Against a prevailing trend in New Testament scholarship, he boldly asserted that “it is possible to write the story of Jesus’ life.” It is singularly noteworthy that a Jewish scholar was interested in Jesus. It is especially important to recognize that Flusser also made a good case for the position that “among the Jews of post-Old Testament times Jesus is the one about whom we know most.”

In the first decades of the twentieth century some Jewish experts claimed that Jesus’ exhortation to love one’s enemies was dangerously misleading and unrealistic. C. G. Montefiore, a liberal Jewish scholar and equitable critic, to whom New Testament experts admit indebtedness, accurately pointed out that most Jews branded Jesus’ exhortation to “love your enemies” as “impracticable and therefore undesirable or harmful” (Some Elements of the Religious Teaching of Jesus According to the Synoptic Gospels [1910]). Flusser argued, however, that Jesus’ genius is most evident in his exhortation to love those who hate you, which according to Flusser (received viva voce) is the Semitic substratum to “love your enemies” (Matthew 5:44). This refreshing argument reveals that Jesus, who had been portrayed as a barrier separating Jews and Christians today, is being perceived as a bridge for appreciative dialogue.

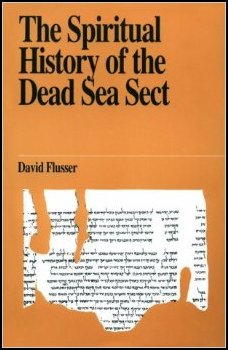

After his retirement Professor Flusser was impressively fruitful. Jewish Sources in Early Christianity (New York: Adama Books, 1987; Tel Aviv: MOD Books, 1989) contains his reflections on Jesus’ life and teaching, on Paul and the Dead Sea Scrolls, and on many related subjects. One of Flusser’s claims is that the Dead Sea Scrolls have revolutionized our understanding of Early Judaism and of Christian Origins. His thoughts on the history and theology of the authors of the Dead Sea Scrolls are attractively presented in The Spiritual History of the Dead Sea Sect (Tel Aviv: MOD Books, 1989). Flusser proves to be a faithful guide “on a journey into the Jewish past.” He rightly shows the reader the “dark side” as well as the beauty of the thoughts in the Dead Seal Scrolls. The reader of Flusser’s works will discern why the Qumran Scrolls have “brought about a revolution in the history of human thought.”

After his retirement Professor Flusser was impressively fruitful. Jewish Sources in Early Christianity (New York: Adama Books, 1987; Tel Aviv: MOD Books, 1989) contains his reflections on Jesus’ life and teaching, on Paul and the Dead Sea Scrolls, and on many related subjects. One of Flusser’s claims is that the Dead Sea Scrolls have revolutionized our understanding of Early Judaism and of Christian Origins. His thoughts on the history and theology of the authors of the Dead Sea Scrolls are attractively presented in The Spiritual History of the Dead Sea Sect (Tel Aviv: MOD Books, 1989). Flusser proves to be a faithful guide “on a journey into the Jewish past.” He rightly shows the reader the “dark side” as well as the beauty of the thoughts in the Dead Seal Scrolls. The reader of Flusser’s works will discern why the Qumran Scrolls have “brought about a revolution in the history of human thought.”

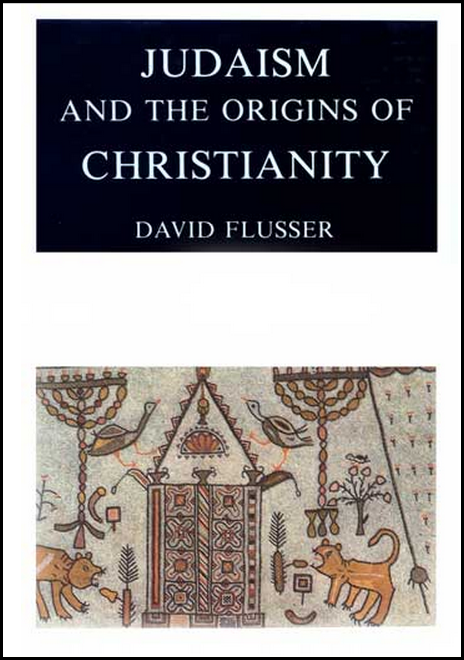

The major publishing event is to be credited to the Magnes Press of the Hebrew University. In Judaism and the Origins of Christianity, which appeared in 1988, are collected 41 articles in 725 printed pages (plus an introduction and plates), covering the years from 1952 up to 1988. Some articles are translated from Hebrew; the following are new:

- From the Essenes to Romans 9:24-33

- The Magnificat, the Benedictus, and the War Scroll

- Jesus’ Opinion about the Essenes

- The Slave of Two Masters

- Messianology and Christology in the Epistle to the Hebrews

- Messianic Blessings in Jewish and Christian Texts

- The Fourth Empire—an Indian Rhinoceros?

- No Temple in the City

- A Rabbinic Parallel to the Sermon on the Mount

- The Didache and the Noachic Commandments

- “I am in the Midst of Them” (Matthew 18:20)

- Jesus and the Sign of the Son of Man

- A Lost Jewish Benediction in Matthew 9:9

- Two Anti-Jewish Montages in Matthew

The articles are arranged under three categories: The Dead Sea Scrolls and the New Testament, Jewish and Christian Apocalyptic, and Ancient Judaism and Christianity.

The articles are arranged under three categories: The Dead Sea Scrolls and the New Testament, Jewish and Christian Apocalyptic, and Ancient Judaism and Christianity.

Flusser’s critical eye was primarily on the Jewish world prior to the burning of the Temple by the Roman soldiers in 70 C.E. He stressed the revolutionary significance of the Dead Sea Scrolls, the central importance of the Jewish apocrypha and pseudepigrapha, and the valuable—albeit edited—witness to early Jewish religious customs and life found in Rabbinic Literature. For Flusser, who was devoted to his Jewish faith, “Jesus was a Jew who spoke to other Jews. Therefore without a doubt, Jesus and his message belong within the framework of the Judaism of his time: it is an inseparable part of it.” Here Flusser is both a pioneer and a scholar who represents the turning of the tide in international scholarship. The “Selected Bibliography” at the end of the volume (pp. 723-25) indicates the breadth of Flusser’s scholarship, from the Old Testament to the medieval Josippon, and from archaeology to theology.

Flusser also was a man of our times. His studies are relevant and programmatic. He poured much energy and time into making his articles available to interested readers because he was convinced that his research “is destined to eliminate innate prejudices and to foster a better understanding of the ancient sources of two world religions—Judaism and Christianity. However it is only indirectly linked with the so-called Christian-Jewish dialogue. The volume is a result of scholarly research.” Indeed one of the best ways to improve understanding and appreciation among Jews and Christians, in my own judgment, is to focus on the brilliant creativity of early Jews, like Hillel and Jesus, Gamaliel and Paul, using the canons of historical criticism. Jews and Christians should seek ways to celebrate not only the similarities but also the differences between Jews and Christians. A similar thought is found in Flusser’s “Hillel’s Self-Awareness and Jesus” (pp. 509-14). In this work, he argues that Jesus is not to be denied—either by Jewish or Christian scholars—that exalted self-awareness attributed to him by the four Evangelists. Rather it is to be fruitfully compared with Hillel’s high self-perceptions, which apparently influenced Jesus. Moreover, in “A New Sensitivity in Judaism and the Christian Message” (pp. 469-89), Flusser celebrates Jesus’ unique message to love those who hate you, which is a development of the best thoughts in Jewish theology (Leviticus 19:18, Ben Sira 27-28, Jubilees, Testament of Benjamin, and statements by Hillel, Hanina, Ben Uzziel, Rabbi Akiba).

Obviously, Flusser acknowledged the eventual schism of Christianity from Judaism. In “Jewish-Christian Schism” (pp. 617-44), Flusser perceives what he labels “centrifugal forces” at work in the world of the first century. These forces eventually pushed the Palestinian Jesus Movement to the fringes of Judaism. Between the death of Jesus and the conversion of Paul a “high Christology” emerged; it was the most significant cause of the split. Paul became its chief spokesman. His position was not acceptable to most Jews. In Paul’s writings and in the Gospel of Matthew we begin to see the disenfranchisement of Jews as the people of God and their replacement by the Gentiles as the true people of God. This tendency in the first century became in later centuries the “Christian” perception, owing to the desire of the new religion to be found acceptable in Greco-Roman culture.

Today we should not stress the differences among Jews and Christians. There are also vast differences in thought and practice among Jews and among Christians. We should attempt, rather, to peer back into the time before the schism widened. In the early twenty-first century we are in a good position to explain this separation and to re-discover the common heritage of the two great religions: Judaism and Christianity. This new position is due to the discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls, the monumental discoveries made by archaeologists, a better historical perception of Jesus from Nazareth, and the new methodology and sensitivity found in many leading experts, especially David Flusser.

This hope was in evidence in January 1990, when Professor Flusser spoke for over two hours to an international seminar. At the end he expressed the dream that the veil will drop from the eyes of Christians and Jews and they will begin to recognize each other as brothers and sisters.