Revised: 15-Feb-2008

Most academics would question the value of attempting to identify material originating from the historical Jesus because Matthew, Mark and Luke are not historical narratives in the modern sense. They would argue that what may be authentic and originate from reliable eyewitness accounts cannot be separated with objectivity or confidence from other homiletic, liturgical, polemical or apologetic accretions. In essence, the effort would be doomed to failure from the start. Conservative Protestant spokesmen such as pastors and preachers would have their own reservations about such a project. For them, the Gospels are authentic and reliable in every sense, and their message infallible. They would view any attempt to separate historical fact from commentary as unnecessary.

For different reasons, both groups would not be enthusiastic about pursuing a methodology whose aim is to isolate the earliest (and presumably the most historical) elements of the Synoptic Tradition. On the one hand, post-modern academics know that any portrait one offers as a realistic representation of Jesus probably reflects the ideas and prejudices of the portraitist as much as the likeness of the subject. On the other hand, theological conservatives know that a strict academic approach cannot address fully the Bible’s unique and multifaceted character. They would be reluctant to support efforts that critically mutilate a living text.

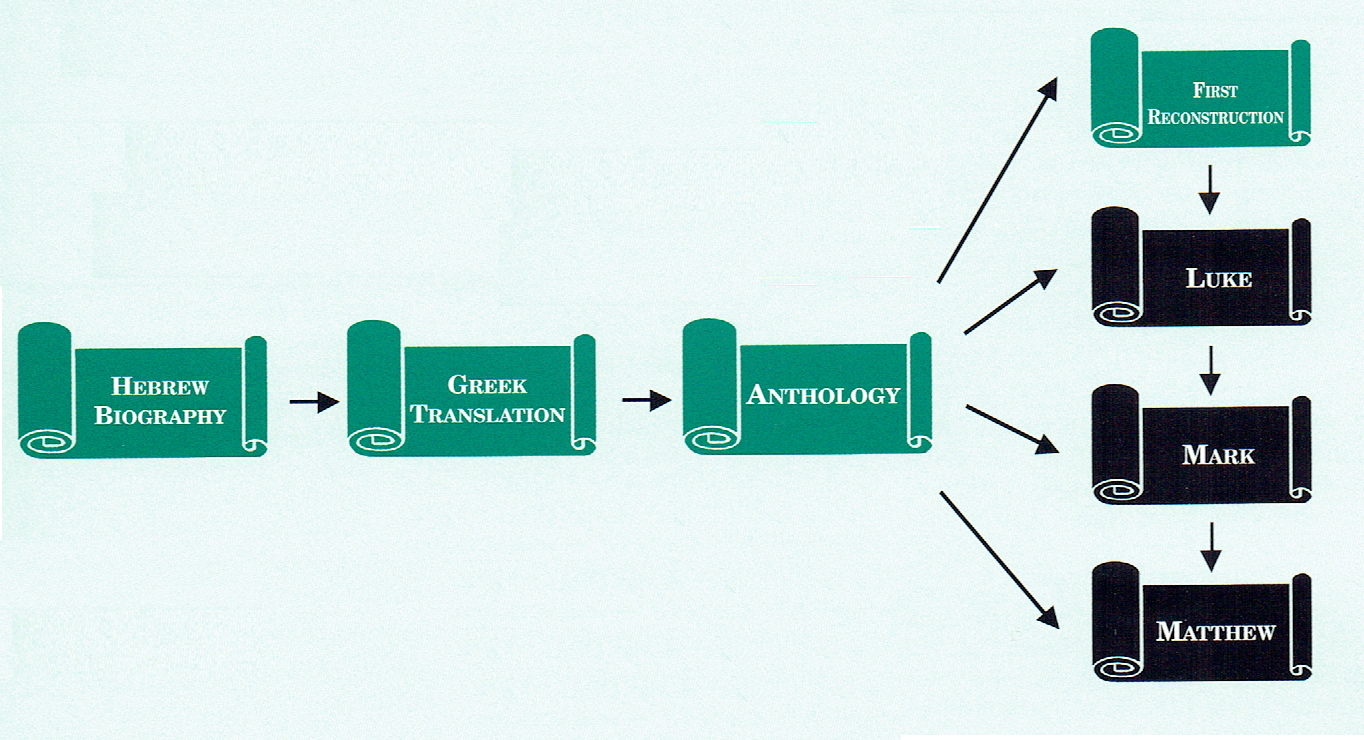

I subscribe to Robert L. Lindsey’s two-document source theory of Lukan priority. As a subscriber, I own a worn Synopsis of the Four Gospels and read Matthew, Mark and Luke with a critical eye. When reading critically, I try to locate material that emanates from the longer and earlier of the two hypothetical sources to which Luke presumably had access. I also assume that in addition to relying on Mark, Matthew used this same long source years after Luke wrote his Gospel. To identify places where this hypothetical source may be percolating through the Greek of the Synoptic Gospels, I look for two clues: 1) Hebraisms embedded in the Greek, especially places where their presence is concentrated; and 2) congruity of thought and content with other writings of the Late Second Temple period and with early rabbinic literature. In essence, as I work from my Synopsis, I pick-and-choose my way down the parallel columns in an effort to isolate and consolidate material emanating from this source. Although these two controls ensure a modicum of objectivity, the process is still quite subjective.

Toward the goal of reducing subjectivity and giving life-support to my critically mutilated Synoptic texts, I would add another, very different type of control to the two mentioned above. To appreciate how this third control might work, we must exit momentarily both the lecture hall and pulpit and enter the domain of radical (and recognized) religious experience.

Mother Teresa © 1986 Túrelio (via Wikimedia-Commons), 1986 / Lizenz: Creative Commons CC-BY-SA-2.0 de

Mother Teresa stands among the great personalities of the last millennium. Although this Nobel Peace Prize recipient did not write theological treatises, her simple sayings are laden with theological significance. As a friend of the forgotten, she earned a formidable reputation, and living among those she served, she enjoyed absolute credibility. She prayed regularly for the sick and on occasion received inspired words of encouragement and guidance for the benefit of those around her. Few would challenge the claim that she excelled in obedience as a modern practitioner of Jesus’ teachings. In Synoptic parlance, this woman entered the kingdom of heaven. For these reasons, I have selected her as a model for introducing the third control.

Jesus’ distinctive conceptual approach to the kingdom of heaven and his response to its dynamism are foundational to the Christian faith. If the kingdom of heaven (according to the Synoptic depiction of it) has remained constant for the past two millennia (except for some expansion and contraction), then Mother Teresa’s words and eyewitness accounts of her work should contain relevant clues for the task of isolating the authentic elements of the Synoptic Tradition. One potential way of gathering those clues would be to search her sayings, writings and interviews for quotations of and allusions to Synoptic passages. Such quotations and allusions could then be collected and perhaps even recorded in an index. I have a hunch that those passages toward which Mother Teresa inclined overlap considerably with the Synoptic material that Lindsey’s theory fingers as authentic.

What advantages may be gained by making a saint part of a text-critical methodology? As a start, it may reduce subjectivity. I cannot imagine that Mother Teresa kept abreast of scholarly trends in Synoptic research. Her problems were of another hue, and she was guided in her choice of Synoptic verses by other considerations. One of those considerations was her uncritical, unscholarly understanding of the kingdom of heaven. Assuming that the kingdom of heaven is conceptually stable through time and its dynamism persists, then agreement between her perception of it and that which emerges from a particular methodological approach may be noteworthy.

Absorbing a modern saint into a text-critical methodology might also make the methodology more compatible with the Bible as a sacred tome. Literary theories can shed much light on Scripture. They can help us listen more attentively as we read. Nevertheless, they cannot adequately accommodate all facets of a sacred text. Form, source and textual criticism are useful tools in the hands of skilled exegetes. For example, they allow scholars to identify scribal errors and accretions. Yet a purely critical approach runs the risk of draining the Bible of its vitality. A “saint-critical methodology” may enable readers to engage more of the authentic elements of the Synoptic Tradition on their own terms. This creative approach could help resuscitate living texts suffering from dismemberment or dehydration. It also implies that in addition to narrow-halled universities and seminaries, other campuses may be fertile for Synoptic learning. Who knows what sublime exegetical insights may have been gleaned, if a few more New Testament scholars had opted for spending a sabbatical on-loan to the frail saint of Calcutta?