An extremely interesting discussion is now taking place on the Bible Translation Discussion List (Bible-Translation@lists.kastanet.org). Jack Kilmon has stated (13Nov08), “Jesus/Yeshua’s native language was Aramaic. That is no longer disputed in serious scholarship,” and (15Nov08), “There is no evidence whatsoever that ordinary people spoke Hebrew in the late 2nd temple period.”

Contra Kilmon: Hebrew was a living language in first-century Israel, part of a multilingual environment (Hebrew, Aramaic and Greek). Jewish teachers of that period (first-century tannaim from both Galilee and Judea) ordinarily passed on their teachings in Hebrew. For example, parables were preserved in Hebrew. Shmuel Safrai writes,

The parable was one of the most common tools of rabbinic instruction from the second century B.C.E. until the close of the amoraic period at the end of the fifth century C.E. Thousands of parables have been preserved in complete or fragmentary form, and are found in all types of literary compositions of the rabbinic period, both halachic and aggadic, early and late. All of the parables are in Hebrew. Amoraic literature often contains stories in Aramaic, and a parable may be woven into the story; however the parable itself is always in Hebrew (b. Baba Qam. 60b; or b. Sotah 40a). There are instances of popular sayings in Aramaic, but every single parable is in Hebrew” (“Spoken and Literary Languages in the Time of Jesus,” in Jesus’ Last Week: Jerusalem Studies in the Synoptic Gospels, Vol. 1 [ed. R. S. Notley, M. Turnage and B. Becker; Leiden: E. J. Brill, 2005], 238; see also Randall Buth and Brian Kvasnica, “Temple Authorities and Tithe Evasion: The Linguistic Background and Impact of the Parable of the Vineyard, the Tenants and the Son,” in Jesus’ Last Week, 58, n. 17).

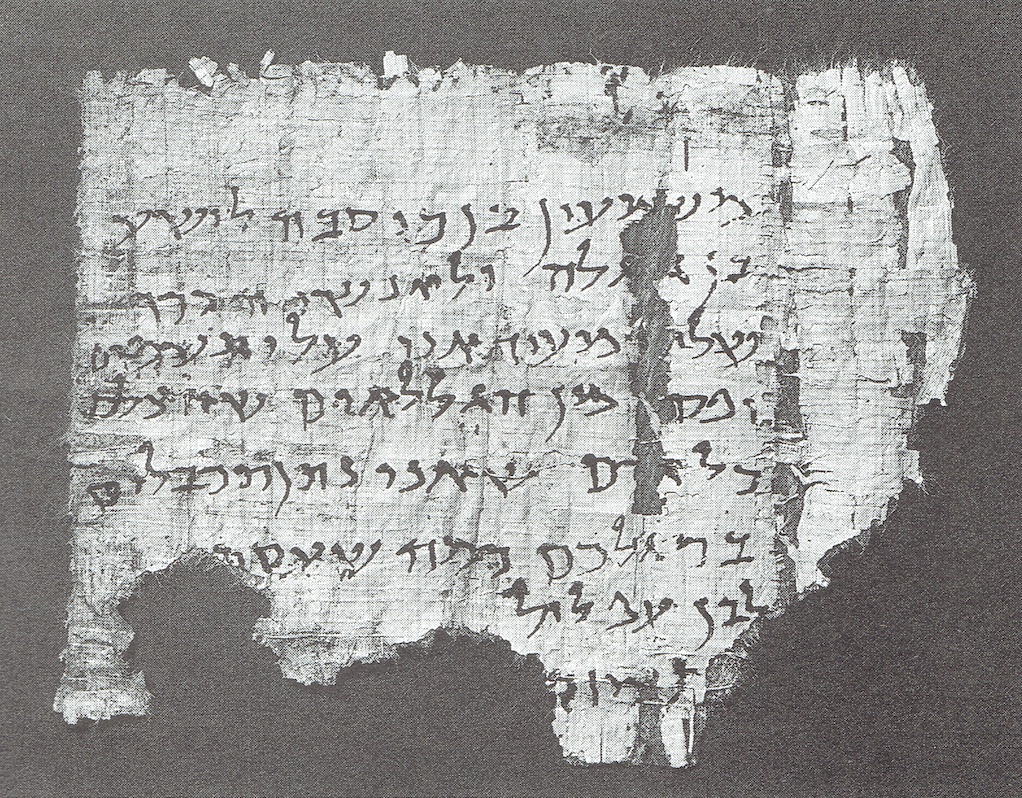

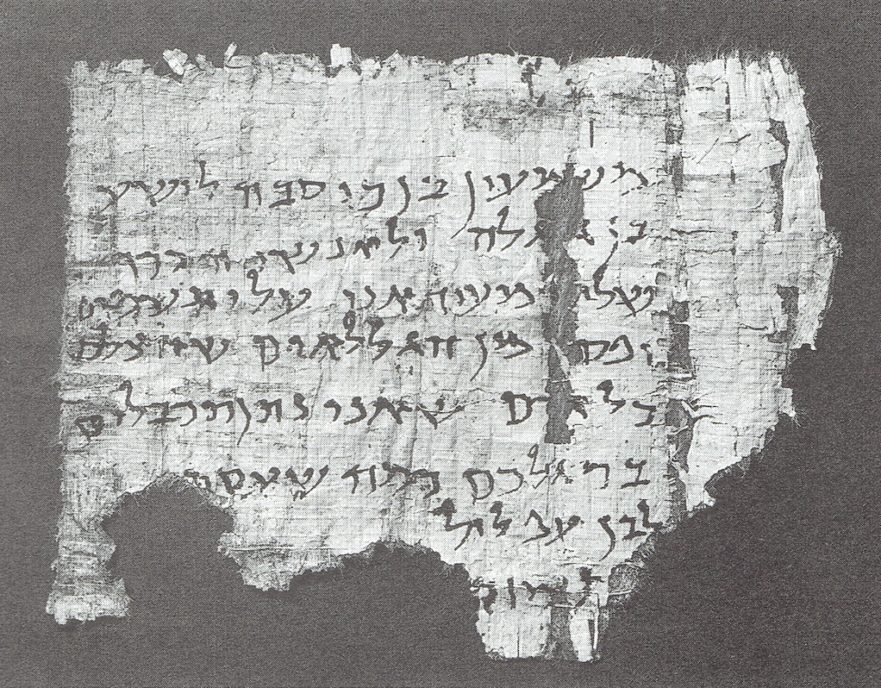

Hebrew also was typically chosen for written accounts of Jewish religious significance, as evidenced by post-biblical writings such as Ben Sira, 1 Maccabees (according to consensus), by the Qumran texts and tannaic Hebrew texts. On the significant lack of Aramaic targum at Qumran, see Randall Buth, “Where Is the Aramaic Bible at Qumran? Scripture Use in the Land of Israel.”

The Second Temple period epigraphical material is more frequently Hebrew than Aramaic. Just last month Israeli archaeologists unearthed part of a first-century limestone sarcophagus cover with the Hebrew inscription בן הכהן הגדול (ben hacohen hagadol, son of the High Priest).

If it is likely that the literary language of Jews in the time of Jesus was Hebrew, and the ordinary language of teaching was Hebrew, what was the primary spoken language of the Jewish residents of the Land? It appears that it, too, was Hebrew.

Randall Buth has pointed out to me a fascinating indication that Hebrew was the spoken language in the first century. The Jewish historian Josephus describes an incident that took place during the siege of Jerusalem (War 5:269-272). Josephus relates that watchmen were posted on the towers of the city walls to warn residents of incoming stones fired from Roman ballistae. Whenever a stone was on its way, the spotters would shout “in their native tongue, ‘The son is coming!’” (War 5:272). The meaning the watchmen communicated to the people was: האבן באה (ha-even ba’ah, the stone is coming). However, because of the urgency of the situation, these words were clipped, being abbreviated to בן בא (ben ba, son comes). (This well-known Hebrew wordplay is attested in the New Testament: “God is able from these avanim [stones] to raise up banim [sons] to Abraham” [Matt. 3:9 = Luke 3:8].)

The wordplay (and pun) that Josephus preserves is unambiguously Hebrew. This wordplay does not work in Aramaic: kefa ate (the stone is coming), or the more literary, avna ata, when spoken rapidly, do not sound like bara ate (the son is coming). Another Aramaic word for “stone,” aven, which is related to Hebrew, changes the gender of the verb and, in any case, does not work with “son.”

Certainly, a warning about an incoming missile needs to be as brief as possible (and, of course, shouted in the language of speech). How many words would an English-speaking soldier use to warn his unit of an incoming artillery shell? The Hebrew-speaking spotters on the walls of the besieged city of Jerusalem needed only two, and these they abbreviated to one syllable each.

Comments 2

It is commonly held by Judaic scholars and all orthodox Jews, that since the time of Ezra, the Jewish temple services and the language spoken in the temple and synagogues of worship was Hebrew. This is made clear in several references in the New Testament:

— Luke 23:38: “And a superscription also was written

over him in letters of Hebrew,

THIS IS THE KING OF THE JEWS.” …….

If Yehshua and the Jews spoke ARAMAIC, there would ot have been a superscription in Hebrew (rathe than Aramaic).

This superscription was written for the vast majority of Israelis,

the common folk. Just this single scriptural proof alone

is overwhelmingly compelling that Hebrew was very much alive

and still in use in Israel at that time.

— In ACTS 26:14 Paul states: “And when we had all fallen to the earth, I heard a voice speaking unto me, and saying in the Hebrew tongue, ‘Saul, Saul, why persecutest thou Me? It is hard for thee to kick against the goads.’ ”

— In ACTS 21:40 we are told that: “And when he had given him licence, Paul stood on the stairs, and beckoned with the hand unto the people. And when there was made a great silence, he spake unto them in the Hebrew tongue, saying,”

— In ACTS 22:1 we are told: “Men, brethren, and fathers, hear ye my defence which I make now unto you. 2(And when they heard that he spake in the Hebrew tongue to them, they kept the more silence: and he saith,)”

These scriptural passages make clear that the Jews spoke Hebrew at this time and the only reason for this was that Hebrew was the language of the temple and worship services were read from the Hebrew scripture.

I am not sure I find this argument convincing. If I consider Latin as a close analogy, it’s ‘death’ as a language was gradual. It remained in formal settings long after it died as a colloquial language. So, given the importance of Hebrew I. The eArly centuries, I would expect a certain amount of use in academic areas and on inscriptions long after it had stopped to be a language of the everyday. This seems more consistent with the first century, than as the every day language that this article seems to argue for.