|

For Agnes Dyck and the Bonhoppers. |

The first of January, celebrated around the world as New Year’s Day, is also the eighth day of Christmas and, as such, the Feast of the Circumcision and Naming of Jesus. Of course, no one knows on what day of the year Jesus was actually born, but since it has become traditional to celebrate Jesus’ birth on the 25th of December, it follows that the first of January is the day on which Christians celebrate the circumcision and naming of Jesus.[1]

According to the Gospel of Luke, “At the end of eight days, when he was circumcised, he was called Jesus, the name given by the angel before he was conceived in the womb” (Luke 2:21; RSV). In fact, the Gospel of Luke is the earliest source to mention the Jewish custom of naming an infant on the day of his circumcision.[2] In the first century, circumcision was a rite performed in the home and celebrated by family and friends (cf. Luke 1:59).[3] It was significant not only because it was the fulfillment of a commandment, but through circumcision a Jewish boy was understood to enter God’s covenant.[4] In a sense, a Jewish boy was not born an Israelite, he became an Israelite by virtue of his circumcision.

Although only the Gospel of Luke records the event of Jesus’ circumcision, the Apostle Paul mentions the significance of Jesus’ circumcision for Gentile believers on more than one occasion.[5] In the Epistle to the Colossians Paul wrote:

In him [i.e., Jesus—JNT]…you were circumcised with a circumcision made without hands, by putting off the body of flesh in [or, by means of—JNT] the circumcision of Christ. (Col. 2:11; RSV)

Despite Paul’s vehement contention that Gentile believers in Jesus should not formally convert to Judaism (which would have required male circumcision),[6] Paul nevertheless maintained that Jesus’ circumcision had vicarious effects for Gentile believers.[7] Exactly how Jesus’ circumcision vicariously affects Gentiles is not altogether clear, but it is possible that we find a partial answer in Paul’s Epistle to the Ephesians, where Paul writes:

…remember that at one time you Gentiles in the flesh, called “the foreskin” by what is called “the circumcision” (that done by [human] hands)—remember that you were at that time separated from Christ, alienated from the commonwealth of Israel, and strangers to the covenants of promise, having no hope and without God in the world. But now in Christ Jesus you who once were far off have been brought near in the blood of Christ. (Eph. 2:11-13; RSV adapted)

Rembrandt van Rijn, “The Circumcision,” oil on canvas (1661). This painting correctly depicts the circumcision of Jesus not in the Temple, but in the family’s private dwelling. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

The questions raised by this passage are manifold: What is the covenant from which Gentiles were excluded? What blood could have brought Gentiles into the covenant? Why is circumcision such a big part of the discussion? Perhaps the key to understanding this passage is to recognize that the main issue is exclusion from God’s covenant with Abraham. Israelites enter the covenant through circumcision, but since Gentiles are not circumcised on the eighth day they are obviously excluded from the covenant unless they undergo formal conversion to Judaism. Jesus’ crucifixion could not vicariously gain entrance for Gentiles into the Abrahamic covenant, but if by “the blood of Christ” Paul referred to the blood of Jesus’ circumcision, then we can comprehend how Jesus’ blood could vicariously bring Gentiles into the covenant between God and Abraham.[8] Paul seems to suggest that Jesus was circumcised on behalf of the Gentiles so that a believing Gentile’s foreskin need not be a barrier to entering the blessings of the covenant between God and Abraham. Paradoxically, the very thing that would seem to separate Jesus from Gentile believers—circumcision—is the thing that unites Gentile believers to Jesus and the Jewish people. What a wonderful thing to celebrate on New Year’s Day!

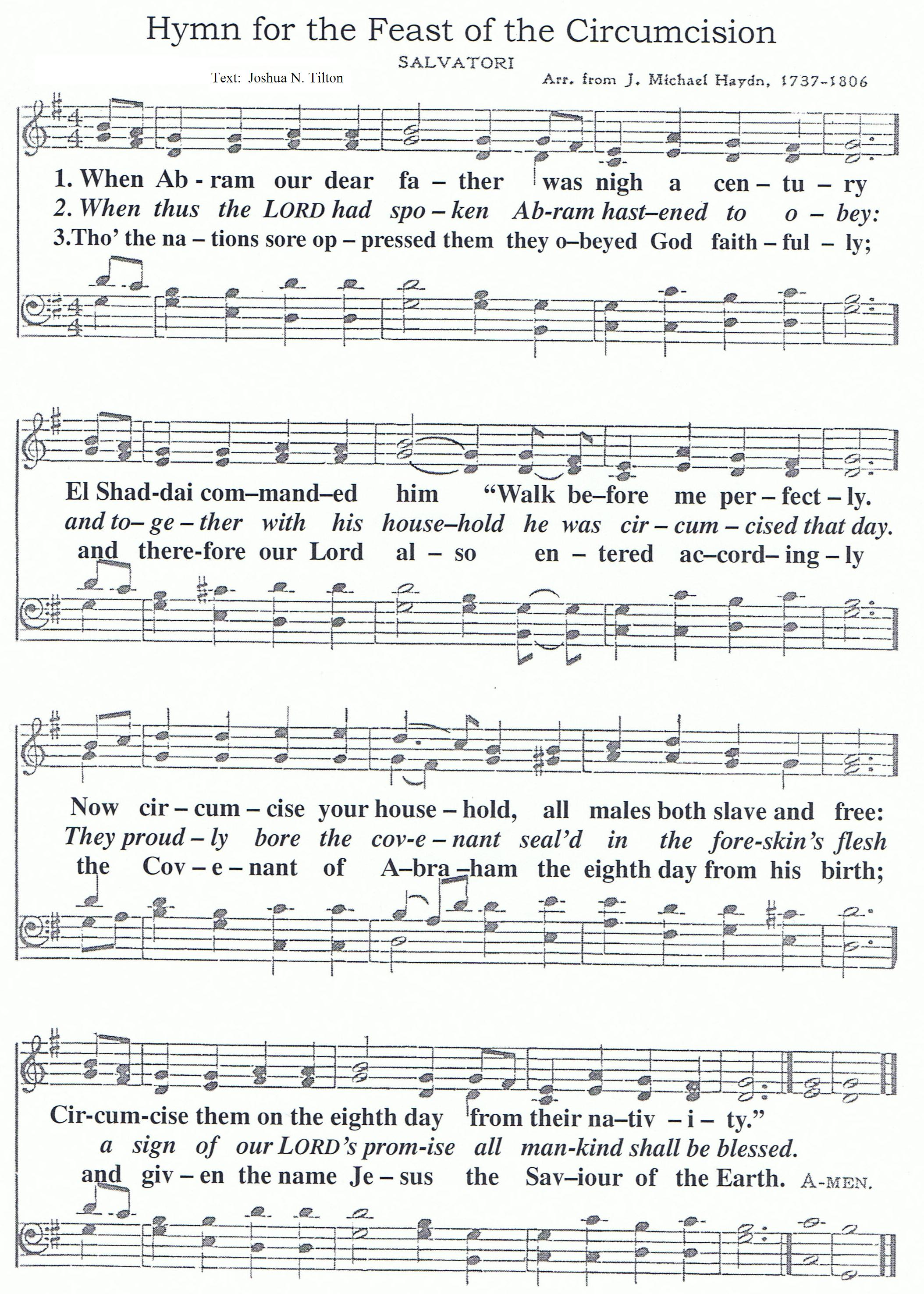

Although hymns have gone out of style these days, for traditionalists such as myself, here is a hymn for the Feast of the Circumcision which I composed in the days when I served as the pastor of a small Baptist congregation:

I wish to thank my wife, Lauren Asperschlager, for proofreading this blog, thus saving me from embarrassing mistakes.

- [1] The Feast of the Circumcision and Naming of Jesus is still marked on the liturgical calendars of several Christian denominations. ↩

- [2] See Shmuel Safrai, “Naming John the Baptist”; Chana Safrai, “Jesus’ Devout Jewish Parents and Their Child Prodigy.” ↩

- [3] See Shmuel Safrai, “Home and Family,” in The Jewish People in the First Century (2 vols.; CRINT I.2; ed. Shmuel Safrai and Menahem Stern; Philadelphia: Fortress, 1976), 767. ↩

- [4] The vocabulary of “entering the covenant” via circumcision is attested as early as the Dead Sea Scrolls: באו…בברית אברהם (“they entered…the covenant of Abraham”; CD XII, 11). Similar terminology is found in rabbinic literature: אבי הבן צריך ברכה לעצמו ברוך אשר קדשנו במצותיו וצונו להכניסו בבריתו של אברהם אבינו (“the father of the son must recite a separate blessing [for circumcision] for himself: Blessed is he who sanctified us through his commandments and commanded us to cause him [i.e., the eight-day-old boy—JNT] to enter the covenant of our father Abraham”; t. Ber. 6:12). ↩

- [5] See further, David Flusser and Shmuel Safrai, “Who Sanctified the Beloved in the Womb,” Immanuel 11 (1980): 46-55. ↩

- [6] See 1 Cor. 7:17-19; Gal. 5:2; 6:15; Phil. 3:2-9. ↩

- [7] On Paul and circumcision see Paula Fredriksen, “Paul, Purity, and the Ekklēsia of the Gentiles,” in The Beginnings of Christianity (ed. Jack Pastor and Menachem Mor; Jerusalem: Yad Izhak Ben-Tzvi, 2005), 205-217; idem, “Judaizing the Nations: The Ritual Demands of Paul’s Gospel,” New Testament Studies 56 (2010): 232-252; Peter J. Tomson, “Paul’s Jewish Background in View of His Law teaching in 1Cor 7,” in Paul and the Mosaic Law (ed. James D. G. Dunn; Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2001), 251-270. ↩

- [8] In rabbinic literature the blood of circumcision is referred to as דם ברית (“blood of [the] covenant”; t. Ber. 6:13). ↩

Comments 4

Can we also add into this G-d’s promise to Abraham “in you all nations will be blessed” read as “ingrafted” by Paul because of a wordplay on ברכה meaning “ingrafted” in Mishnaic Hebrew? The connection to circumcision seems to gain weight then doesn’t it?

Margie

The article begins… “ Of course, no one knows on what day of the year Jesus was actually born, but since it has become traditional to celebrate Jesus’ birth on the 25th of December, it follows that the first of January is the day on which Christians celebrate the circumcision and naming of Jesus.”

I am still surprised and somewhat disturbed when I read this common assumption! It is not impossible nor that difficult to know at least the approximate birthday of Jesus.

We know that Jesus was conceived about three months after John the Baptist. We know the conception date of John within a few days because we know the month of his father Zecharias’ priestly service when the angel told him his aged wife would conceive when he went home. Given normal gestation times for both infants, these dates place the birth of Jesus in the autumn. In fact right in the Feast of Tabernacles!

This corresponds well with the Apostle John’s striking and unusual words in reference to the incarnation that the eternal Word of God literally “tabernacled” among us John 1:14.

Since Jesus was sacrificed at Passover, and He sent his Spirit at Pentecost, it stands to reason that the feast of Tabernacles is not only a celebration of his return in glory but also of his birth and of the beginning of his earthly ministry 3-1/2 years before his crucifixion.

So please let’s stop perpetrating biblical ignorance. And let’s stop rcapitulating to the greatest justification for continuation of the pagan “Christmas” winter solstice /saturnalia festival. Let’s start patterning our worship after God’s own ordained holy days and stop caving into the pagan ignorance that surrounds us!

Otherwise, great article. In fact I appreciate this site very much, having just discovered it. Love to hear your thoughts on this.

Author

Dear David,

Thanks for your kind words about my article. I’m not sure, however, that I can share your certainty regarding the (approximate) date of Jesus’ birth. I don’t think we can know at what time of year Zechariah was serving in the Temple when Gabriel appeared to him. As I’m sure you know, each of the priestly courses served in the Temple twice a year, but I can find nothing in Luke to indicate whether Zechariah was on his first or second rotation when the events described in Luke 1 took place. (See the useful discussion in Shmuel Safrai’s article “A Priest of the Division of Abijah,” under the subheading, “Times of Service.”) We can’t just assume that it must have been on his first (or second) rotation simply because it fits our preferred timeline.

I would also challenge your assertion that since other important events in Jesus’ life took place on Jewish festivals “it stands to reason” that he must have been born on a Jewish festival as well. I’m not sure it works that way. Although it might seen fitting to place Jesus’ birth at the Feast of Sukkot (Tabernacles), our aesthetic sensibilities or theological preferences are not proof that this was the case. Wanting something to be true isn’t evidence that it is true. Alas. There are some things that we just can’t know for sure.

Joshua

Great research, when I read that same passage, “… But now in Christ Jesus you who once were far off have been brought near in the blood of Christ.” My pre-trained Christian mind goes straight toward his blood as shed on the cross, but your interpretation actually keeps the parallel Paul seems to be making about Messiah’s blood directly in line with his other language surrounding circumcision. Thank you!