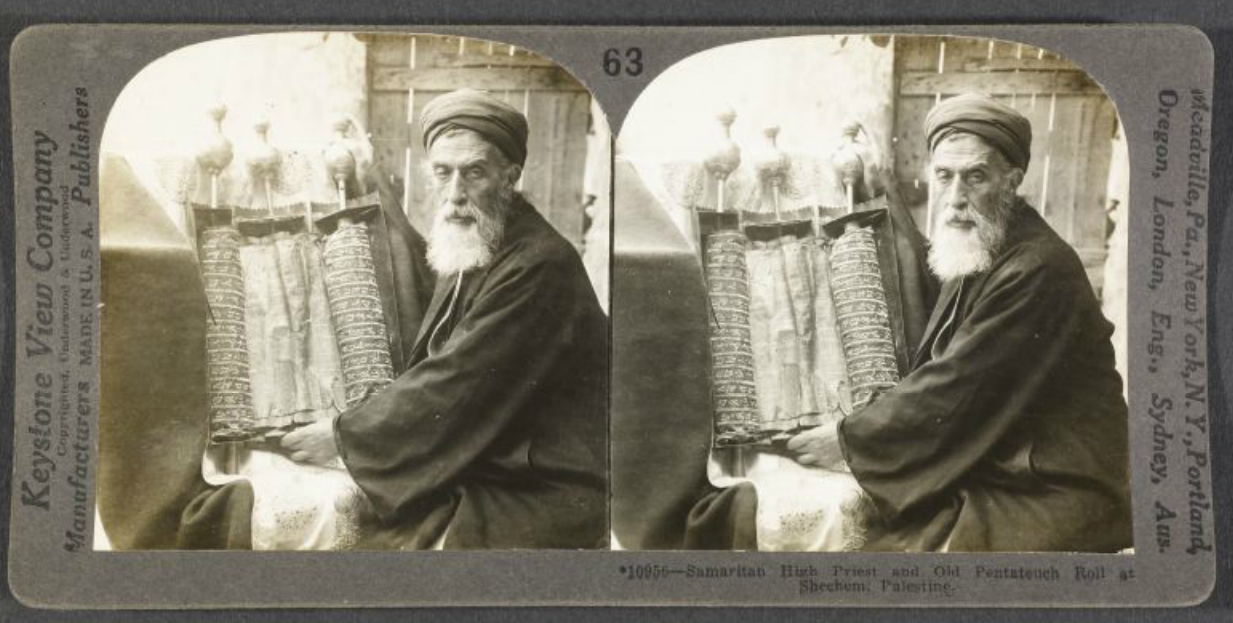

Jacob ben Aaron ben Shelamah was the Samaritan high priest from 1861 until his death in 1916.[1] Born in Nablus in 1841, Jacob ben Aaron (Ya‘qūb bin Hārūn) was the nephew of the previous Samaritan high priest, but since his uncle died without having a son Jacob assumed the high priestly office.[2] Jacob ben Aaron was not only the spiritual leader of his people, he also represented the Samaritans to Western scholars who, in the late nineteenth century, had begun to take an interest in the history and customs of the Samaritan people.

Due to their interest, Jacob ben Aaron was commissioned to write a book about Samaritan traditions, which is variously entitled Kitâb aṭ-Ṭuqûsât (“Book of Religious Practices”) or Kitâb al-I‘tiqâdât (“Book of Principles”).[3] This book consists of ten chapters, many of which have been translated into English, and some of which are now in the public domain. They are as follows:

- I: On the Origins and History of the Samaritans[4]

- II: On Mount Gerizim[5]

- III: On the Sabbath[6]

- IV: On Circumcision[7]

- V: On the Calendar

- VI: On Ritual Purity[8]

- VII: On Dietary Laws

- VIII: On Marriage

- IX: On the Torah

- X: On Burial Practices[9]

Other writings by Jacob ben Aaron include:

- Jacob, son of Aaron, The Messianic Hope of the Samaritans (ed. William E. Barton; trans. Abdullah ben Kori; Chicago, Ill.: The Open Court Publishing Company, 1907).

- Jacob, son of Aaron, The Book of Enlightenment for the Instruction of the Inquirer (ed. William E. Barton; trans. Abdullah ben Kori; Sublette, Ill.: Puritan Press, 1913).

In his writings Jacob ben Aaron expresses traditional Samaritan views and sometimes engages in polemics against Judaism and the Jewish community. Nevertheless, Jacob ben Aaron’s writings are of great importance as an historical source for understanding Samaritan culture, beliefs, and practices.

Although he was a high priest, copyist of sacred texts, translator and author, Jacob ben Aaron was a poor man whose family, together with the rest of the Samaritan community, suffered hardships under Ottoman rule.[10] Of his ten children, eight died during his lifetime. In one of the Pentateuchs he copied, Jacob wrote about his sorrow over the deaths of three of his children who died in the period during which the Pentateuch was being prepared:

I labored hard in the writing of this Torah…from the opening of the wounds and strife and grief which came upon me from the death of my three children. And a change came upon me as in fasting I considered the distress which had come upon me in His name. I was motivated to proceed with this Torah and I was not able to contain my bitterness, but I did not stop….[11]

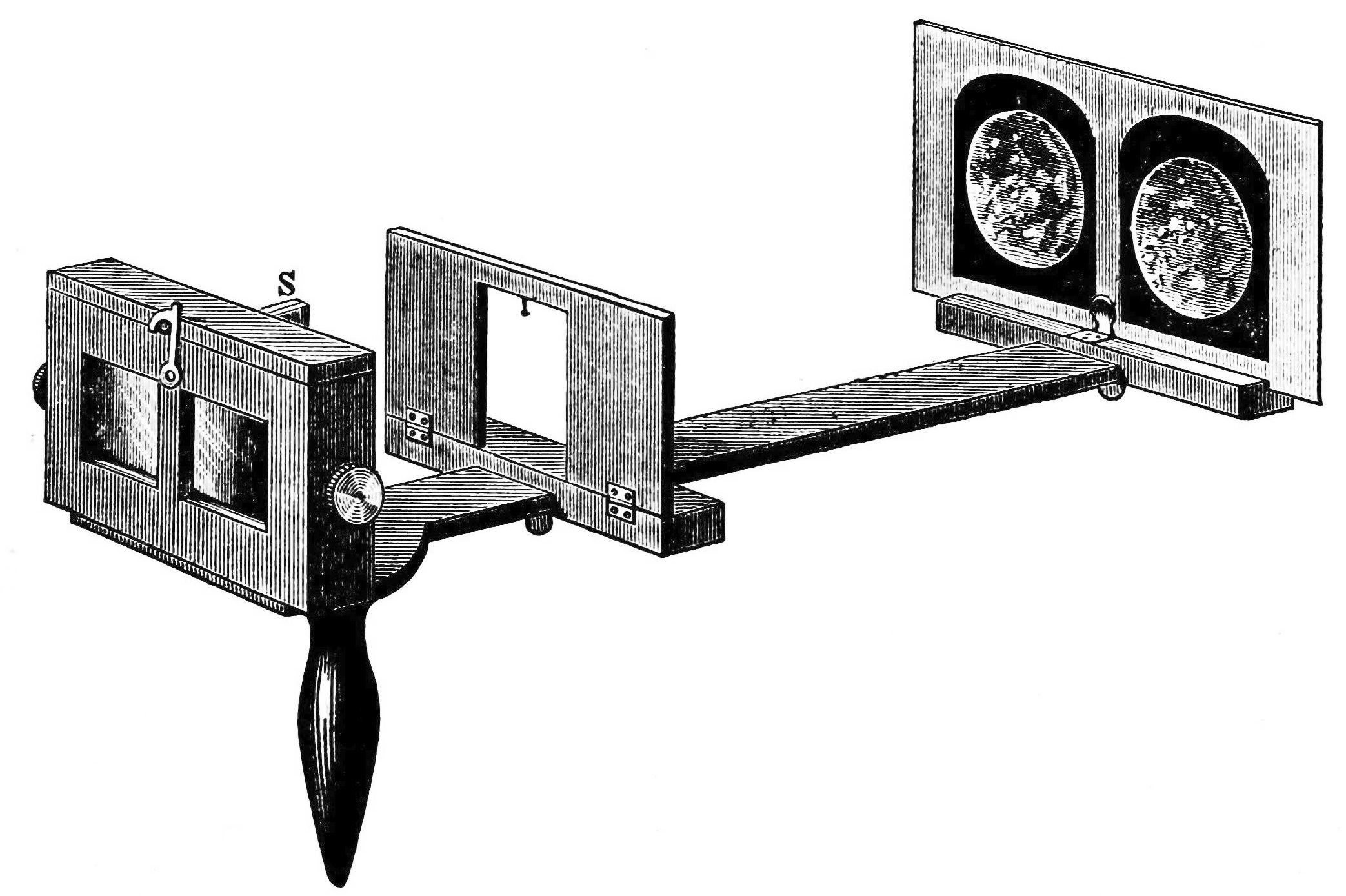

The image of Jacob ben Aaron shown above is from a stereograph, a form of photography popular in the nineteenth century in which two images from slightly different angles were taken, which, when viewed through a stereoscope, gave the viewer a three-dimensional effect.

- [1] Robert T. Anderson and Terry Giles, The Keepers: An Introduction to the History and Culture of the Samaritans (Peabody, Mass.: Hendrickson, 2002), 138.

- [2] Jacob, son of Aaron, The History and Religion of the Samaritans (ed. William E. Barton; trans. Abdullah ben Kori; Oak Park, Ill.: Puritan Press, 1906), 5.

- [3] See I. R. M. Boid, “The Samaritan Halachah,” in The Samaritans (ed. Alan D. Crown; Tübingen: Mohr [Siebeck], 1989), 634.

- [4] Published as Jacob, son of Aaron, The History and Religion of the Samaritans (ed. William E. Barton; trans. Abdullah ben Kori; Oak Park, Ill.: Puritan Press, 1906).

- [5] Published as Jacob, son of Aaron, Mount Gerizim, the One True Sanctuary (ed. William E. Barton; trans. Abdullah ben Kori; Oak Park, Ill.: Puritan Press, 1907).

- [6] Published as Jacob, son of Aaron, “The Samaritan Sabbath,” Bibliotheca Sacra 65 (1908): 430-444.

- [7] Published as Jacob, son of Aaron, “Circumcision Among the Samaritans,” Bibliotheca Sacra 65 (1908): 694-710.

- [8] Published in I. R. M. Boid, Principles of Samaritan Halachah (Leiden: Brill, 1997) 124-131 (text), 187-192 (trans.).

- [9] Published in Moses Gaster, The Samaritan Oral Law and Ancient Traditions, Vol. 1, Samaritan Eschatology (London: Search Publishing Company, 1932), 129-187.

- [10] On the conditions the Samaritan community faced in this period, see Nathan Schur, “Samaritan History: The Modern Period (from 1516 A.D.),” in The Samaritans (ed. Alan D. Crown; Tübingen: Mohr [Siebeck], 1989), 113-134, esp. 125-126.

- [11] Anderson and Giles, The Keepers, 138.