| The image featured above, intended to symbolize the Two Ways of Life and Death, which are of central importance to the Didache, was photographed by Imen Bouhajja in Ghar Elmelh, Tunisia (courtesy of Wikimedia Commons). |

How to cite this article: Huub van de Sandt, “The Didache and its Relevance for Understanding the Gospel of Matthew,” Jerusalem Perspective (2016) [https://www.jerusalemperspective.com/16271/].

Premium Members and Friends of JP must be signed in to view this content.

If you are not a Premium Member or Friend, please consider registering. Prices start at $5/month if paid annually, with other options for monthly and quarterly and more: Sign Up For Premium

1. The Didache

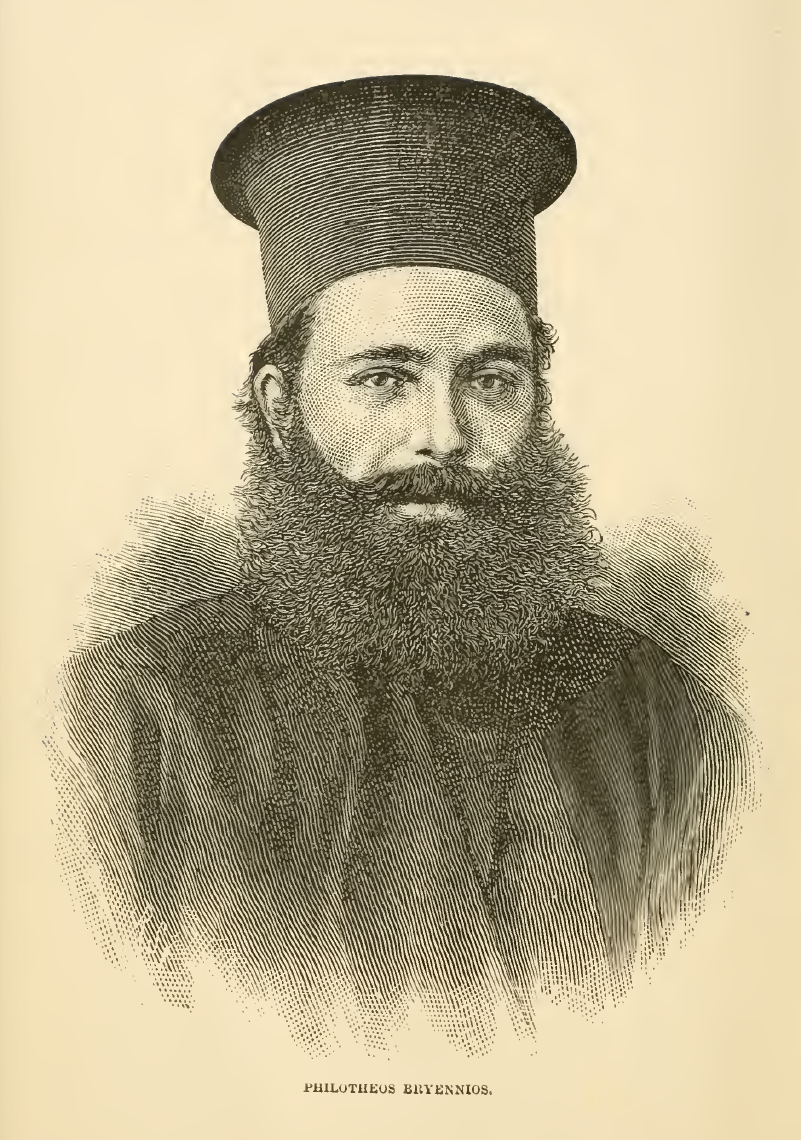

A portrait of Philotheos Bryennios found opposite the title page of Philip Schaff’s The Oldest Church Manual Called The Teaching of the Twelve Apostles (1885). Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

In 1873, Philotheos Bryennios, the metropolitan of Serres (Serrae) in Macedonia, discovered a Greek parchment manuscript in the monastery of the Holy Sepulchre in Constantinople. The document contained several early Christian writings, including the text of the famous Didache. Bryennios edited the treatise in 1883. In 1887, the manuscript was transferred to the Greek patriarchate in Jerusalem where it is still preserved today as Hierosolymitanus 54. In the colophon of the manuscript (folium 120, front side) the name of the scribe and the date are preserved. “Leon the scribe and sinner” was the one who produced this codex, which he completed on Tuesday, 11 June 1056.

The ancient textual basis of the eleventh-century minuscule copied by Leon should be narrowed down to its central part only (fol. 39front-80back). The source of this text, extending from the Letter of Barnabas to the end of the Didache, may have originated in the patristic period.[75] In this article, the text of the Didache (fol. 76front-80back) is studied in isolation from the other works contained in the Jerusalem Manuscript. Of course, there are also a few smaller and fractional witnesses to the text of the Didache. For the establishment of the text of the Didache, however, the bearing of these fragments is meagre.

Premium Members and Friends of JP must be signed in to view this content.

If you are not a Premium Member or Friend, please consider registering. Prices start at $5/month if paid annually, with other options for monthly and quarterly and more: Sign Up For Premium

- [1] This latter rule is not only reflected in the Two Ways 1:2c but is frequently found throughout Jewish, Christian, and Hellenistic sources. About the so called “Golden Rule,” see Philip S. Alexander, “Jesus and the Golden Rule,” in Hillel and Jesus: Comparative Studies of Two Major Religious Leaders (ed. J. H. Charlesworth and L. L. Johns; Minneapolis: Fortress, 1997), 363-388. ↩

- [2] Willy Rordorf and André Tuilier, La Doctrine des douze Apôtres (Didachè) (2nd ed.; Sources Chrétiennes 248 bis; Paris: Cerf, 1998), 24; Kurt Niederwimmer, The Didache: A Commentary (trans. L. M. Maloney; Hermeneia, Minneapolis; Fortress, 1998), 36-38.59-63. ↩

- [3] Such as the Apostolic Church Order, the Epitome of the Canons of the Holy Apostles, the Arabic Life of Shenute, the Ps.-Athanasian Syntagma Doctrinae, and the Fides CCCXVIII Patrum. ↩

- [4] Van de Sandt and Flusser, The Didache, 155-182. ↩

- [5] The early layer of these tractates reflects a lifestyle which is called “derekh hasidut,” the way of the pious. It reveals the teachings of the early Hasidim who, according to Myron B. Lerner, “The External Tractates,” in The Literature of the Sages (ed. S. Safrai; Compendia Rerum Iudaicarum ad Novum Testamentum 2/3; Assen: Van Gorcum-Philadelphia: Fortress, 1987) 367-404 (380), “placed extreme stress on self-deprival and the performance of good deeds and acts of loving kindness.” ↩

- [6] See, e.g., “Hasidim,” Encyclopaedia Judaica (16 vols.; Jerusalem: Keter, 1962), 7:1383-1388; Heinz Kremers, “Die Ethik der galiläischen Chassidim und die Ethik Jesu,” in K. Ebert, Alltagswelt und Ethik (Wuppertal: Peter Hammer Verlag, 1988), 143-156. ↩

- [7] Everett Ferguson, Baptism in the Early Church: History, Theology, and Liturgy in the First Five Centuries (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2009), 202. ↩

- [8] Ferguson, Baptism in the Early Church, for example, considers the “allowance of pouring instead of immersion” as an “anomaly” and “a break with Jewish practice” (206). However, this need not necessarily be a rupture with its Jewish environment. The highlighting of “moral purity,” common in early Christian literature, was also widespread in in Philo’s works and in the Qumran scrolls, see Jonathan Klawans, Impurity and Sin in Ancient Judaism (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000), 64-66; 48-56, 67-91. One may thus view this change in emphasis as an inner-Jewish phenomenon. ↩

- [9] This is not the appropriate place to dig deeper into the distinction between “ritual” and “moral” impurity. Whereas the sources of ritual impurity are mostly confined to natural phenomena, including childbirth, the carcasses of animals, menstrual and seminal emissions, skin disease, or a human corpse, moral impurity results from immoral acts such as sexual sins (Lev. 18:24-30), idolatry (Lev. 19:31; 20:1-3), and bloodshed (Num. 35:33-34). See Klawans, Impurity and Sin, 21-31. ↩

- [10] See for instance Dan. 6:11; 2 En. 51:4; m. Ber. 4:1 (and see also 4:3.7). ↩

- [11] See for example Peter J. Tomson, “The wars against Rome, the rise of Rabbinic Judaism and of Apostolic Gentile Christianity, and the Judaeo-Christians; elements for a synthesis,” in The Image of the Judaeo-Christians in Ancient Jewish and Christian Literature (ed. P. J. Tomson and D. Lambers-Petry; Wissenschaftliche Untersuchungen zum Neuen Testament 158; Tübingen: Mohr, 2003), 1-31 (9-10 and n. 40); Marcello Del Verme, Didache and Judaism: Jewish Roots of an Ancient Christian-Jewish Work (New York-London: T&T Clark, 2004), 185; Jonathan A. Draper, “Christian Self-Definition against the ‘Hypocrites’ in Didache VIII,” in The Didache in Modern Research (ed. J. A. Draper; Arbeiten zur Geschichte des antiken Judentums und des Urchristentums 37; Leiden: Brill, 1996), 223-243. ↩

- [12] Peter J. Tomson, “The Lord’s Prayer (Didache 8) at the Faultline of Judaism and Christianity,” in The Didache: A Missing Piece of the Puzzle in Early Christianity (ed. J. A. Draper and C. N. Jefford; Early Christianity and Its Literature 14; Atlanta: SBL, 2015), 165-187 (183-185). ↩

- [13] See for example Enrico Mazza, The Origins of the Eucharistic Prayer (trans. R. E. Lane; Collegeville, Minn.: Liturgical Press, 1995), 13-18; Niederwimmer, The Didache, 156-160; Alan J. P. Garrow, The Gospel of Matthew’s Dependence on the Didache (Journal for the Study of the New Testament—Supplement Series 254, London: T&T Clark, 2004), 17-19; Van de Sandt and Flusser, The Didache, 309-329; etc. ↩

- [14] See also Aaron Milavec, The Didache: Faith, Hope, and Life of the Earliest Christian Communities, 50-70 C.E. (New York: Newman, 2003), 416-421; Jonathan A. Draper, “Ritual Process and Ritual Symbol in Didache 7-10,” Vigiliae Christianae 54 (2000): 121-158; Matthias Klinghardt, Gemeinschaftsmahl und Mahlgemeinschaft: Soziologie und Liturgie frühchristlicher Mahlfeiern (Texte und Arbeiten zum neutestamentlichen Zeitalter 13, Tübingen: Francke Verlag, 1996), 407-427. ↩

- [15] Jonathan Schwiebert, Knowledge and the Coming Kingdom: The Didache’s Meal Ritual and its Place in Early Christianity (Library of New Testament Studies 373, London: T&T Clark, 2008), 119; Mazza, Origins of the Eucharistic Prayer, 156-159; Van de Sandt and Flusser, The Didache, 316-318. ↩

- [16] Huub van de Sandt, “The Gathering of the Church in the Kingdom: The Self-Understanding of the Didache Community in the Eucharistic Prayers,” in Society of Biblical Literature—Seminar Papers 42 (Atlanta: SBL, 2003), 69-88. ↩

- [17] See Van de Sandt and Flusser, The Didache, 340-341. ↩

- [18] The community is required to “break bread, and give thanks,” expressions that correspond with “broken bread” and “giving thanks” in Did. 9-10. The descriptions in Did. 14:1 seem to refer to one and the same eucharistic ritual. The text associates this meal with the idea of sacrifice (thysia); see Schwiebert, Knowledge and the Coming Kingdom, 167. ↩

- [19] Rordorf and Tuilier, La Doctrine, 64-65. ↩

- [20] William D. Davies and Dale C. Allison, The Gospel according to Saint Matthew (3rd ed.; International Critical Commentary; vols. 1-3, London-New York: T&T Clark, 2004), 1:127-138 and see the list of scholars there adopting a similar position (128). ↩

- [21] For references, see John S. Kloppenborg, “The Use of the Synoptics or Q in Did. 1:3b-2:1,” in Matthew and the Didache: Two Documents from the same Jewish-Christian Milieu? (ed. H. van de Sandt; Assen: Van Gorcum-Minneapolis: Fortress, 2005), 105-129 (105, n. 2). ↩

- [22] R. Hugh Connolly, “Canon Streeter on the Didache,” Journal of Theological Studies 38 (1937): 364-379 (367-370); Frederick E. Vokes, The Riddle of the Didache. Fact or Fiction, Heresy or Catholicism? (The Church Historical Society 32; London: SPCK, 1938), 51-61. ↩

- [23] Minus Did. 8:2b; 11:3b; 15:3-4 and 16:7 according to Garrow, The Gospel of Matthew’s Dependence. ↩

- [24] Édouard Massaux, Influence de l’Évangile de saint Matthieu sur la littérature chrétienne avant saint Irénée (Bibliotheca ephemeridum theologicarum lovaniensium 75; Leuven: University Press-Peeters, 1950; repr. Leuven, 1986), 604-646 (618); Donald A. Hagner, The Use of the Old and New Testaments in Clement of Rome (Novum Testamentum Supplements 34; Leiden: Brill, 1973), 280; Kurt Wengst, Didache (Apostellehre): Barnabasbrief. Zweiter Klemensbrief. Schrift an Diognet (Schriften des Urchristentums 2; Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, 1984), 28; Helmut Köster, Synoptische Überlieferung bei den apostolischen Vätern (Texte und Untersuchungen 65, Berlin: Akademie-Verlag, 1957), at first leaves the question open (198-200), but after having dealt with other similar instances in the Didache, he is inclined to believe that the document is not dependent on (one of) the Synoptic Gospels (240). For a more elaborate version of this section, see my ‘“Do not Give What is Holy to the Dogs” (Did. 9:5d and Matt. 7:6a): the Eucharistic Food of the Didache in its Jewish Purity Setting’, Vigiliae Christianae 56 (2002): 223-46. ↩

- [25] See Elisha Qimron and John Strugnell, Qumran Cave 4 5: Miqsat Maʻaśe ha-Torah (Discoveries in the Judaean Desert 10; Oxford: Clarendon 1994), 52-53. A similar ban applied to chickens as well; see also Elisha Qimron, “The Chicken and the Dog and the Temple Scroll,” Tarbiz 64 (1994) 473-476 (Hebrew) (for an English translation of Qimron’s article, click here). Joshua Tilton kindly provided me with this publication. ↩

- [26] It has been noted that the acquaintance with the above halakha was not restricted to the Qumran community only since it is probably echoed in Rev 22:15 where it says: “Outside are the dogs and sorcerers and fornicators and murderers and idolaters, and everyone who loves and practises falsehood” (compare 21:8). The author of Revelation apparently was familiar with the established halakha of 4QMMT and explains the rule in a spiritual way (See Marc Philonenko, “’Dehors les chiens.’ Apocalypse 22.16 et 4QMMT B 58-62,” New Testament Studies 43 [1997] 445-450). He applies it to the heavenly Jerusalem and considers the “dogs outside” to represent the apostates and false teachers. The text suggests the disciplinary measure of excluding false teachers and those who commit the most grievous sins (the sorcerers, fornicators, murderers and idolaters) from the city. ↩

- [27] Such as in m. Temurah 6:5; t. Temurah 4:11; y. Maʻaśer Šeni 2:5, 53c; b. Temurah 17a; 31a; 33a-b; b. Bekorot 15a (2x); b. Šebuʻot 11b. For the specific quotations of these instances, see the notes in my ‘“Do not Give What is Holy to the Dogs,”’ 229-231. ↩

- [28] Pisqa 118; see H. S. Horovitz (ed.), Siphre d'be Rab I: Siphre ad Numeros adjecto Siphre zutta (Corpus Tannaiticum 3/1; Leipzig 1917; corr. repr Jerusalem: Wahrmann, 1966), 138. ↩

- [29] The Qumran Essenes seem to have anticipated the propensity to extend the sacred meals beyond the altar and the temple in Jerusalem and, like the Qumran group, many other Jews of the Second Temple period observed ritual purity when participating in secular meals; see Huub van de Sandt, “Why does the Didache Conceive of the Eucharist as a Holy Meal?” Vigiliae Christianae 65 (2011): 1-20. ↩

- [30] The wording “as a gentile and tax-collector” in Matt. 18:17b, referring to the punishment of expulsion, stands out from the Matthean gospel as a whole with respect to its pejorative tone. The gist of the expression applies neither to the life of Jesus nor to the Gospel of Matthew. It is improbable that the historical Jesus, who extended the possibility of conversion to the toll-collectors and sinners, would have used this phraseology in such a context. With regard to Matthew, the expression appears to contradict the favourable attitude toward pagans and tax-collectors displayed throughout Matthew’s gospel. It is therefore unlikely that we are dealing here with words pronounced by Jesus or created by Matthew. ↩

- [31] For references, see Niederwimmer, The Didache, 204, n. 10. For a more detailed treatment of this subject, see my “Two Windows on a Developing Jewish-Christian Reproof Practice: Matt. 18:15-17 and Did. 15:3,” in Van de Sandt (ed.), Matthew and the Didache, 173-192. ↩

- [32] See Lawrence H. Schiffman, “Reproof as a Requisite for Punishment,” in Sectarian Law in the Dead Sea Scrolls: Courts, Testimony and the Penal Code (ed. L. H. Schiffman; Brown Judaic Studies 33; Chico Calif.: Scholars, 1983), 89-109 (97-98); this article was published in an almost identical version as “Reproof as a Requisite for Punishment in the Law of the Dead Sea Scrolls,” in Jewish Law Association Studies 2: The Jerusalem Conference Volume (ed. B. S. Jackson; The Jewish Law Association. Papers and Proceedings; Atlanta Ga: Scholars, 1986), 59-74; Moshe Weinfeld, The Organizational Pattern and the Penal Code of the Qumran Sect: A Comparison with Guilds and Religious Associations of the Hellenistic-Roman Period (Novum Testamentum et Orbis Antiquus 2; Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1986), 74-76; Bernard S. Jackson, “Testes singulares in Early Jewish Law and the New Testament,” in Essays in Jewish and Comparative Legal History (ed. B. S. Jackson; Studies in Judaism in Late Antiquity 10; Leiden: Brill, 1975), 172-201 (175-76) and n. 6. ↩

- [33] See Van de Sandt, “Two Windows,” 185-186. ↩

- [34] Florentino García Martínez, “La Reprensión fraterna en Qumrán y Mt 18,15-17,” Filologia Neotestamentaria 2 (1989): 23-40; trans. “Brotherly Rebuke in Qumran and Mt 18:15-17,” in The People of the Dead Sea Scrolls: Their Writings, Beliefs and Practices (ed. F. García Martínez and J. Trebolle Barrera; Leiden: Brill, 1995), 221-232; Schiffman, “Reproof as a Requisite for Punishment,” 94-96. ↩

- [35] See Weinfeld, The Organizational Pattern, 38-41, 75; Jacob Licht, The Rule Scroll: A Scroll from the Wilderness of Judaea: 1QS - 1QSa - 1QSb (Jerusalem: Bialik Institute, 1965), 137 (Hebr.); Michael Knibb, The Qumran Community (Cambridge Commentaries on Writings of the Jewish and Christian World 200 BC to AD 200; Cambridge: University Press, 1987), 115. ↩

- [36] “There is nothing to indicate that he can be received back again;” see Goran Forkman, The Limits of the Religious Community: Expulsion from the Religious Community within the Qumran Sect, within Rabbinic Judaism, and within Primitive Christianity (Coniectanea neotestamentica or Coniectanea biblica: New Testament Series 5; Lund: Gleerup, 1972), 129. See also Ingrid Goldhahn-Müller, Die Grenze der Gemeinde: Studien zum Problem der Zweiten Busse im Neuen Testament unter Berücksichtigung der Entwicklung im 2. Jh. bis Tertullian (Göttinger Theologischer Arbeiten 39; Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1989), 181; Alois Schenk-Ziegler, Correctio fraterna im Neuen Testament: Die “brüderliche Zurechtweisung” in biblischen, frühjüdischen und hellenistischen Schriften (Forschung zur Bibel 84; Würzburg: Echter Verlag, 1997), 298.

On the other hand, Matthew may have incorporated this unit precisely at this very position in his gospel for a special purpose. In Matt. 18, the forensic process passage is set within a literary context of humility (1-5), responsibility (6-9), individual loving care (12-14), forgiveness, and mercy (21-35). Matthew surrounds the traditional segment on fraternal reproof with material promoting a spirit of generosity and unbounded compassionate love. In the light of the wider context of Matt. 18, the regulation in Matt. 18:15-17 displays an essential correspondence with the reproof passage in Did. 15:3. The act of reproach here might have the same purpose as the one in Did. 15:3, that is, to gain a brother by having him listen to the evidence of his culpability and admit his sin. ↩ - [37] See Jean-Paul Audet, La Didachè: Instructions des apôtres (Études bibliques; Paris: Gabalda, 1958), 180 and Schenk-Ziegler, Correctio fraterna, 126-58 (130-32). A more distant parallel is found in T. Gad 6:3: “Therefore, love one another from the heart, and if a man sins against you, speak to him in peace (en eirēnē)....” ↩

- [38] Like for example Did. 7:1.3 (par. Matt. 28:19); Did. 11:2.4 (par. Matt. 10:40); Did. 11:7 (par. Matt. 12:31); Did. 13:1-2 (par. Matt. 10:10); Did. 14:2 (par. Matt. 5:23-24); Did. 16:1-2 (par. Matt. 24:42.44; 25:13); and Did. 16:3-8 (par. Matt. 24-25). See also above, pp. 12-13. ↩

- [39] See Philip Schaff, The Oldest Church Manual, Called the Teaching of the Twelve Apostles (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1886), 18 (on top); James Muilenburg, The Literary Relations of the Epistle of Barnabas and the Teaching of the Twelve Apostles, (Marburg, n.p., 1929), 73; Frederick E. Vokes, The Riddle of the Didache: Fact or Fiction, Heresy or Catholicism? (The Church Historical Society 32; London: SPCK; New York: Macmillan 1938), 19; etc. ↩

- [40] Georg Braumann, “Zum Traditionsgeschichtlichen Problem der Seligpreisungen MT V 3-12,” Novum Testamentum 4 (1960): 253-260 (259-260); Wiard Popkes, “Die Gerechtigkeitstradition im Matthäus-Evangelium,” in Zeitschrift für die neutestamentliche Wissenschaft und die Kunde der älteren Kirche (1989), 1-23 (17). ↩

- [41] See Martin Hengel, “Zur matthäischen Bergpredigt und ihrem jüdischen Hintergrund,” Theologische Rundschau 52 (1987): 355-356; see also 379-380. For the ideological and literary affinity of the first three Beatitudes with the Dead Sea Scrolls, see David Flusser, “Blessed are the Poor in Spirit,” in Judaism and the Origins of Christianity. Collected articles (ed. D. Flusser; Jerusalem: Magnes, 1988), 102-114; repr. from Israel Exploration Journal 10 (1960): 1-13; idem, “Some Notes to the Beatitudes,” in Judaism, 115-125; repr. from Immanuel 8 (1978), 37-47.

↩ - [42] See Shmuel Safrai, “Teaching of Pietists in Mishnaic Literature,” Journal of Jewish Studies 16 (1965), 15-33 (32-33); idem, “Hasidim we-Anshei Maase,” Zion 50 (1984-85), 133-154 (144-154); idem, “Jesus and the Hasidim,” Jerusalem Perspective (1994) 3-22; idem, “Jesus and the Hasidic Movement,” in The Jews in the Hellenistic Roman World. Studies in Memory of Menahem Stern (ed. I. M. Gafni, A. Oppenheimer and D. R. Schwartz; Jerusalem: Graphit, 1996), 413-436 (415) (Hebr.). ↩

- [43] The second half of the Decalogue is even more likely to stand in the background of Matt. 5:21-48 since the last unit (5:43-48) stresses the love of one’s neighbor which, as we have seen, is often used in early Judaism to express in crystalized form the second table of the Decalogue (see Matt. 19:18-19; Rom. 13:8-10; Jas 2:8-11). Rather interestingly, the items “murder” and “adultery” (in this order) also head the rather long catalogue of prohibitions in GTW 2:1-7 and again the list of vices that serves as an explication of the Way of Death in Greek Two Ways 5. Altogether, it does not seem unreasonable to suppose that the first two items in the arrangement of the lists, which are modeled after the second tablet of the Decalogue, are more strung together by tradition than the remainder, which rather seems a haphazard and free adaptation in the various lists. ↩

- [44] b. Menah. 44a, top; b. Ned. 39b; y. Pe’ah 1,15d; Siphre Deut. 79 to Deut. 12:28 in Louis Finkelstein (ed.), Siphre ad Deuteronomium (Corpus Tannaiticum 3/2; Berlin: Jüdischer Kulturbund, 1939; repr. New York: Jewish Theological Seminary, 1969), 145; Siphre Deut. 82 to Deut. 13:1 (ibid., 148), Siphre Deut. 96 to Deut. 13:19 (ibid., 157). ↩

- [45] See the treatise Yir’at Het (“fear of transgression,” and a separate denotation of chapters I-IV and IX of the Derekh Erets Zuta tract) II, 16-17 or Derekh Erets Zuta II, 16-17 according to Marcus van Loopik, ed., The Ways of the Sages and the Way of the World (Texte und Studien zum antiken Judentum 26: Tübingen: Mohr, 1991), 229-231 (with commentary) = Massekhet Derekh Erets I, 26 according to Michael Higger, ed., The Treatises Derek Erez: Masseket Derek Erez; Pirke Ben Azzai; Tosefta Derek Erez (2 vols.; New York 1935; repr., Jerusalem: Makor, 1970), 1:78-79 (Hebr.) and 2:38 (English Translation). ↩

- [46] See Ulrich Luz, “Die Erfüllung des Gesetzes bei Matthäus (Mt 5,17-20),” Zeitschrift für Theologie und Kirche 75 (1978): 398-435; repr., in trans. “The Fulfilment of the Law in Matthew (Matt. 5:17-20),” in Studies in Matthew (ed. U. Luz; Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2005), 185-218 (197); Robert Guelich, The Sermon on the Mount: A Foundation for Understanding (2nd ed.; Waco TX: Word, 1983), 135. 156; Luz, Matthäus, 1:230; Albert Descamps, “Essai d’interprétation de Mt 5,17-48: Formgeschichte ou Redactionsgeschichte?,” Studia Evangelica 1 (1959): 156-173 (163); Jacques Dupont, Les Béatitudes 3: Les évangélistes (Études Bibliques; Paris: Gabalda, 1973), 251, n. 2; J. P. Meier, Law and History in Matthew’s Gospel: A Redactional Study of Mt. 5:17-48 (Analecta biblica 71; Rome: Biblical Institute Press, 1976), 116-119; Davies and Allison, Matthew 1:501. ↩

- [47] See also Matt. 23, where Matthew levels the usual charge of hypocrisy (vv. 4-7) against the “scribes and Pharisees” and attacks the Jewish community leadership (of his own post A.D. 70 situation?) in seven woe oracles, in which Jesus condemns the “scribes and Pharisees” seven times; see David C. Sim, The Gospel of Matthew and Christian Judaism: The History and Social Setting of the Matthean Community (Studies of the New Testament and Its World; Edinburgh: T&T Clark, 1998), 130-131. See also Petri Luomanen, Entering the Kingdom of Heaven: A Study on the Structure of Matthew’s View of Salvation (Wissenschaftliche Untersuchungen zum Neuen Testament 2/101; Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 1998), 85. 120. ↩

- [48] See also Matthias Konradt, “Rezeption und Interpretation des Dekalogs im Matthäusevangelium” in The Gospel of Matthew at the Crossroads of Early Christianity (ed. D. Senior; Bibliotheca ephemeridum theologicarum lovaniensium 243; Leuven: Peeters, 2011), 131-158 (135-154). ↩

- [49] Most commonly, the specific antithetical formulations of the first, second, and fourth antitheses (Matt. 5:21-22. 27-28. 33-34a) are considered pre-Matthean while the antithetical pattern in the remainder of the series is assumed to be a secondary arrangement on the basis of the earlier three. This means that those antitheses, showing a radicalisation of the commandments rather than a direct opposite character, are generally considered to have been received by Matthew in antithetical form. In short, the first, second and fourth antitheses are traditional (pre-Matthean) while the other three (with Lukan parallels) are assigned to Matthew’s redaction; see Rudolph Bultmann, Die Geschichte der synoptischen Tradition (8th ed.; Forschungen zur Religion und Literatur des Alten und Neuen Testaments 29; Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht 1970), 143-144; Ulrich Luz, Matthäus: Mt 1-7 (Evangelisch-katholischer Kommentar zum Neuen Testament 1/1; Zürich: Benziger-Verlag, 1985), 246 (though he is inclined to believe that the fourth antithesis is redactional too); Maarten J. J.Menken, Matthew’s Bible: The Old Testament Text of the Evangelist (Bibliotheca ephemeridum theologicarum lovaniensium 173; Leuven: University Press-Peeters, 2004), 265-266; Jan Lambrecht, The Sermon on the Mount. Proclamation and Exhortation (Good News Studies 14; Wilmington Del: Glazier, 1985), 94-95; Davies and Allison, Matthew, 1:504-505 and many others. ↩

- [50] See Van de Sandt and Flusser, Didache, 176-179, 216-234. ↩

- [51] See above, p. 26 (“keep aloof from everything hideous and from what even seems hideous”) and compare also the following statement:

Keep aloof from everything hideous and from whatever seems hideous lest others suspect you of transgression

in Yir’at Het I, 13 according to Van Loopik, The Ways, 194-197 (with commentary) = Massekhet Derek Erets I, 12 according to Higger, The Treatises Derek Erez, 1:63 (Hebr.) and 2:35 (English translation). ↩

- [52] Graham N. Stanton, A Gospel for a New People: Studies in Matthew (Edinburgh: T&T Clark, 1992), 303-304; Guelich, The Sermon on the Mount, 360-363, 379-381; Hans Dieter Betz, The Sermon on the Mount: A Commentary on the Sermon on the Mount, including the Sermon on the Plain (Matthew 5:3-7:27 and Luke 6:20-49) (Hermeneia; Minneapolis: Fortress, 1995), 518; etc. ↩

- [53] Jewish tradition attributes a negative form of this saying to Hillel who presents the Rule as the summation of the Law. According to b. Shab 31a, Hillel summarized the essence of the whole Law by rendering the negative form of the Golden Rule (“Whatever is hateful to you, do it not unto your fellow”) and adding: “the rest is a mere specification.” The reduction of the laws to basic principles very much resembles our passage in Did. 1:2-3. In 1:2, the essential core of the Way of life is found in the double love commandment combined with the negative form of the Golden Rule. These three precepts which have special prominence and serve as the basic elements of the Way of Life are then followed by the clause: “The explanation of these words is as follows.” ↩

- [54] See Georg Strecker, Die Bergpredigt: Ein exegetischer Kommentar (Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1984), 161; Luz, Matthäus 1:395-396; Clayton N. Jefford, The Sayings of Jesus in the Teaching of the Twelve Apostles (Supplements to Vigiliae Christianae 11; Leiden: Brill, 1989), 25-26 and the Appendix A (146-159). See also Davies and Allison, Matthew, 1:696-698. ↩

- [55] Adelbert Denaux, “Der Spruch von den zwei Wegen im Rahmen des Epilogs der Bergpredigt (Mt 7,13-14 par. Lk 13,23-24): Tradition und Redaktion,” in Logia. Les Paroles de Jésus—The Sayings of Jesus (ed. J. Delobel; Bibliotheca ephemeridum theologicarum lovaniensium 59; Leuven: University Press-Peeters, 1982, 305-335 (322-323); Davies and Allison, Matthew, 1:696-698. ↩

- [56] John the Baptist had previously employed this image of judgment in Matt. 3:10 against the Pharisees and Sadducees. In Matthew everyone, whether disciples, Pharisees and Sadducees, are judged by one law. ↩

- [57] See Davies and Allison, Matthew, 1:721-722; Luz, Matthäus, 1:537-538; Joachim Gnilka, Das Matthäusevangelium (Herders theologischer Kommentar zum Neuen Testament 1/2; Freiburg: Herder, 1988), 1:282; W. Wiefel, Das Evangelium nach Matthäus (Theologischer Handkommentar zum Neuen Testament 1; Leipzig: Evangelische Verlagsanstalt, 1998), 156; Floyd V. Filson, A Commentary on the Gospel According to St. Matthew (2nd ed.; Black’s New Testament commentaries; London: Black, 1971), 108. ↩

- [58] In his treatment of the minor sins, Jesus’ argument in Matthew seems rather more rigorous than the line of reasoning in the Two Ways or in the early stratum of Derekh Erets. Although the loss of temper, a lustful look, or the taking of an oath do not replace the acts of murder, infidelity and perjury, they are valued in the Sermon on the Mount as sins in their own right, incurring the same penalty as murder or adultery. The view that anger equals murder and that lust equals adultery, is toned down in the Greek Two Ways 3:1-6 (and in, say, Yir’at Het II, 16-17 as well). The passage in the Greek Two Ways 3:1-3 appears largely to represent preventive measures to protect someone from transgressing weighty commandments. ↩

- [59] In addition to the double love commandment and the single commandment to love one’s neighbour (or its variant version in the Golden Rule) also the second table of the Decalogue was commonly seen as summarizing the essentials of the Law as may be derived from instances in Pseudo-Phocylides, Sentences 3-7 and Rom. 13:8-10. ↩

- [60] See, e.g., Davies and Allison, Matthew, 3:38; Warren Carter, Matthew and the Margins: A Sociopolitical and Religious Reading (The Bible and Liberation Series; Maryknoll NY: Orbis, 2000), 387; Luz, Matthäus, 3:120. For a more elaborate version of this section, see my “Eternal Life as Reward for Choosing the Right Way: The Story of the Rich Young Man (Matt. 19:16-30),” in Life Beyond Death in Matthew’s Gospel: Religious Metaphor or Bodily Reality? (ed. W. Weren, H. van de Sandt, J. Verheyden; Biblical Tools and Studies 13; Leuven: Peeters, 2011), 107-127. ↩

- [61] Davies and Allison, Matthew, 3:43. ↩

- [62] See Pierre Bonnard, L’Évangile selon Saint Matthieu (Commentaire du Nouveau Testament 2/1; 4th ed.; Genève: Labor et Fides, 2002), 288: “ce mot est peut-être une allusion aux catéchumènes de l’Église matthéenne.” ↩

- [63] See also Menken, Matthew’s Bible, 211-212. ↩

- [64] See Deut. 30:15-20; Lev. 18:5; Prov. 6:23; Mal. 2:4-5; Bar. 3:9; Ps. Sol. 14:2; Rom. 7:10; 4 Ezra 14:30; m.’Abot 2:7. ↩

- [65] See for example also Jefford, The Sayings of Jesus, 54-56. 62; Garrow, The Gospel of Matthew’s Dependence, 240-241, 247-248. ↩

- [66] The second table of the Decalogue has nevertheless been expanded here with specific elements, including pederasty, magic, sorcery, abortion, infanticide and additional injunctions. ↩

- [67] See Guelich, The Sermon on the Mount, 135. 156; Luz, Matthäus, 1:230; Meier, Law and History, 116-119; Davies and Allison, Matthew, 1:501. ↩

- [68] Davies and Allison, Matthew, 3:46; Warren Carter, Households and Discipleship: A Study of Matthew 19-20 (Journal for the Study of the New Testament: Supplement Series 103; Sheffield: JSOT, 1994), 117; Luz, Matthäus, 3:46. 123-125; Joachim Gnilka, Das Matthäusevangelium (1988), 2:165. ↩

- [69] See also Wim J. C. Weren, “The Ideal Community According to Matthew, James, and the Didache,” in Studies in Matthew’s Gospel: Literary Design, Intertextuality, and Social Setting (ed. W. J. C. Weren; Biblical Interpretation Series 130; Leiden: Brill, 2014), 222-247 (232-235); Matthias Konradt, “Die volkommene Erfüllung der Tora und der Konflikt mit den Pharisäern im Matthäusevangelium,” in Das Gesetz in frühen Judentum und im Neuen Testament (ed. D. Sänger, M. Konradt and C. Burchard; Novum Testamentum et Orbis Antiquus 57; Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2006), 129-152 (152); idem, “The Love Command in Matthew, James, and the Didache,” in Matthew, James and Didache: Three Related Documents in Their Jewish and Christian Settings (ed. H. van de Sandt and J. K. Zangenberg; Society of Biblical Literature Symposium Series 45; Atlanta: SBL, 2008), 271-288 (274-278); William R. G. Loader, Jesus’ Attitude towards the Law: A Study of the Gospels (Wissenschaftliche Untersuchungen zum Neuen Testament 2/97; Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 1997), 226-227. 269. ↩

- [70] As seen above, the diverse precepts in the Sermon in Matt. 5:17-7:12 and the Way of Life in Did. 1:2-4:14 are organized by and subsumed under the love command (Matt. 7:12 and Did. 1:2). ↩

- [71] See also C. Coulot, “La Structuration de la péricope de l’homme riche et ses différentes lectures (Mc 10,17-31; Mt 19,16-30; Lc 18,18-30),” Recherches de Science Religieuse 56 (1982): 240-252 (249). ↩

- [72] For more specifics, see my “Eternal Life as Reward,” 121-124. ↩

- [73] Jacques Dupont, “Le logion des douze thrônes (Mt 19,28; Lc 22,28-30),” Biblica 45 (1964): 355-92 (378); Filson, Gospel According to St. Matthew, 210. Jesus was the judge who authoritatively interprets Torah. In the Antitheses of Matt. 5:21-48 Jesus seems to use the controlling clause “but I say to you” to expound the demands of Torah and in Matt. 11:27 the power to disclose “these things” to infants is delivered to the Son so as to reveal the Father to whom he chooses. ↩

- [74] See also Huub van de Sandt, “James 4,1-4 in the Light of the Jewish Two Ways Tradition 3,1-6,” Biblica 88 (2007): 38-63; Darian R. Lockett, “Structure or Communicative Strategy: The ‘Two Ways’ Motif in James’ Theological Instruction,” Neotestamentica 42 (2008): 269-287. See also Matthew Larsen, and Michael Svigel, “The First Century Two Ways Catechesis and Hebrews 6:1-6,” in Draper and Jefford, The Didache, 477-496. ↩

- [75] Huub van de Sandt and David Flusser, The Didache: Its Jewish Sources and its Place in Early Judaism and Christianity, (Compendia rerum iudaicarum ad Novum Testamentum 3/5; Assen: Van Gorcum-Minneapolis: Fortress, 2002), 16-24. ↩