How to cite this article: Ronny Reich, “Jewish Burial Customs in the First Century,” Jerusalem Perspective 33/34 (1991): 22 [https://www.jerusalemperspective.com/19631/].

The process of Jewish burial in the Second Temple period took place in two stages. First, the dead person was buried on a ledge or in a loculus of a rock-hewn tomb. Then after about one year, when the body had decomposed, family members of the deceased returned to the tomb, gathered the bones and put them into a small box of stone or wood called an ossuary. Sometimes more than one person’s bones were gathered into an ossuary, but they were always the bones of family members – a husband and wife, a child and one of his or her parents, brothers or other relatives.

In many cases the names of the dead were inscribed on the ossuary, and sometimes also the family relationship. Frequently additional details about the deceased were added such as a nickname, profession or other biographical detail. The ossuary inscriptions are brief and were written in one of the three languages in use in the period: Hebrew, Aramaic and Greek.

According to the halachah, contact with corpses, tombs or graves transmitted the highest degree of ritual impurity, and care was taken to limit such contact. Burial was forbidden within settlements, and cemeteries were required to be at least fifty cubits (twenty-five meters) from a settlement’s boundaries (Mishnah, Bava Batra 2:9).

However, as new houses were built, boundaries did not remain constant, and it was ruled that a tomb or cemetery which became surrounded by settlement on two or more of its sides must be moved (Tosefta, Bava Batra 1:11). Tombs which were discovered by chance and those which created a public nuisance also were required to be moved (Tosefta, Ahilot 16:9). The principle was that daily life should continue to take place as normal, and if a cemetery or individual tombs interfered with this, it was not only possible but necessary to move them to another place.

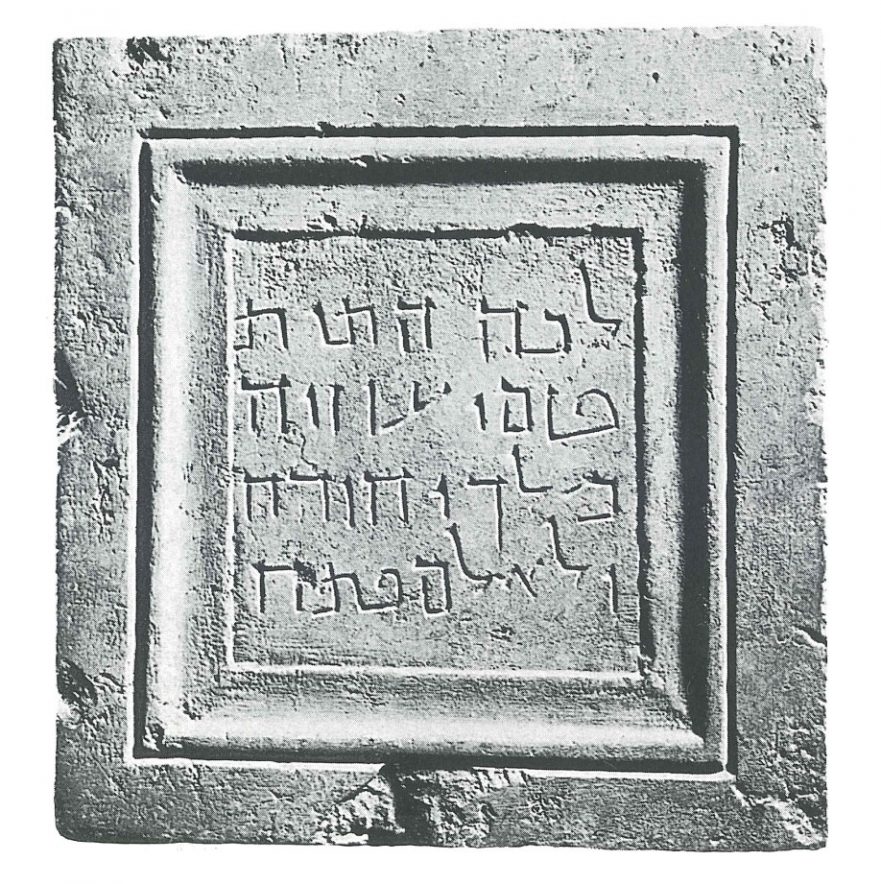

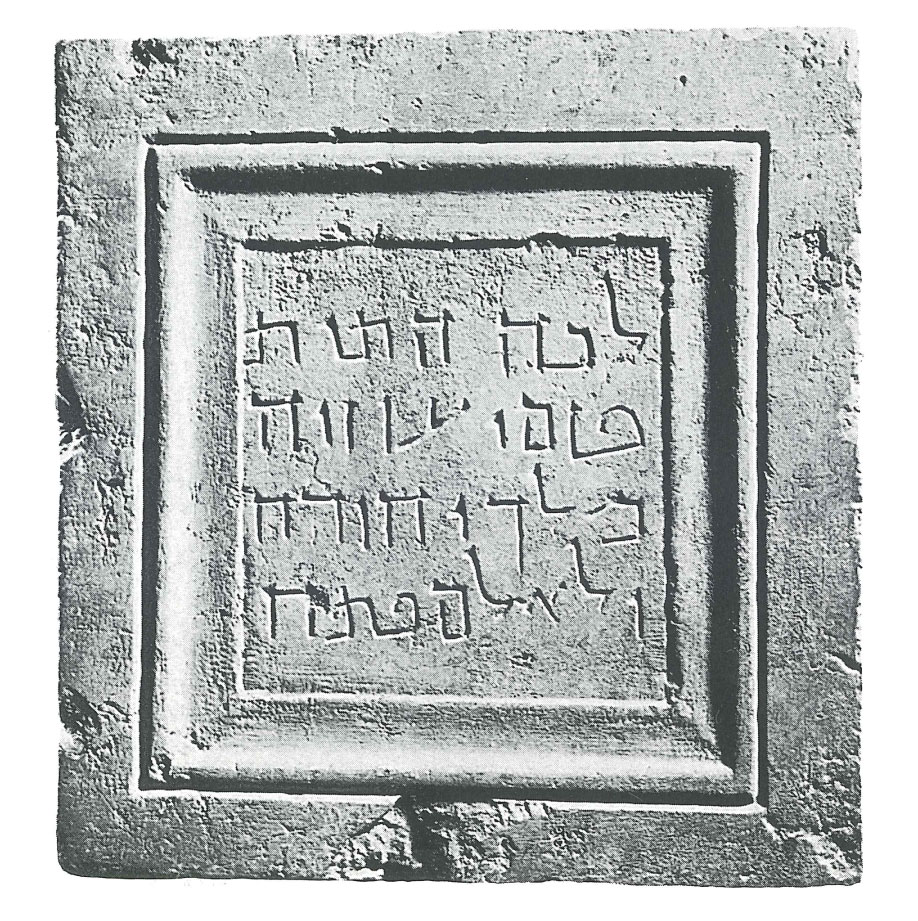

The classic example of this religious ruling being carried out is indicated in the Second Temple period inscription found in Jerusalem which at one time had been affixed to the tomb hewn for the reburial of the bones of Uzziah king of Judah. The inscription states explicitly that Uzziah’s bones had been moved from their original burial place to the new site.