|

|

Although the Gospels tell the story of Jesus, and are therefore set at a chronologically earlier period than the rest of the New Testament writings, they were not the first New Testament documents to be composed. The epistles of Paul are certainly older than the canonical Gospels of Matthew, Mark, Luke and John.

Determining the date of any particular Gospel is a difficult task. Scholars have to take into account internal as well as external evidence to reach their conclusions. By internal evidence we mean clues within the text of each Gospel that might hint at the date of its composition. For instance, if it could be shown that a particular Gospel quoted another work of a known date or alluded to a datable event after Jesus’ ascension, this would constitute internal evidence of the date of the Gospel’s composition. By external evidence we mean references to a particular Gospel in some other datable writing, which would prove that that Gospel had been composed sometime prior to the source that quotes it. Another type of external evidence is the existence of early manuscripts of the Gospels. If those manuscripts can be dated, we can be sure the Gospels were composed prior to those dates.

None of the evidence, whether internal or external, is unequivocal. For instance, the Didache (ca. 100 C.E.) quotes “the Gospel,” but not always in a form that is identical to any of the canonical Gospels. Most of the Didache’s quotations of “the Gospel” are similar to verses in the Gospel of Matthew, but it is possible that the Didache reflects the source(s) known to the author of Matthew rather than the Gospel of Matthew itself. For a discussion of the relationship between the Didache and the Gospel of Matthew, check out Huub van de Sandt’s article “The Didache and its Relevance for Understanding the Gospel of Matthew” on this website.

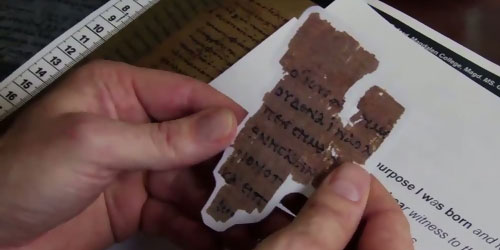

𝔓104, an early witness to the Gospel of Matthew dating to the second century C.E. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

To give another example, scholars are not agreed whether Jesus’ prophecies of the destruction of Jerusalem and the Temple in the Gospel of Luke betray knowledge of the events as they unfolded in 70 C.E. Whereas some scholars see in Luke 19:41-44 and Luke 21:20-24 unmistakable traces of the author of Luke’s knowledge of the course of the Roman siege of Jerusalem, other scholars see in these prophecies generic descriptions of a siege that almost anyone could have predicted. How one views these prophecies will influence one’s dating of the Gospel of Luke. Similar cases pertain to the other three Gospels.

Another factor in dating the Gospels is one’s understanding of how the Synoptic Gospels (Matthew, Mark and Luke) are related to one another and how the Synoptic Gospels are related to the Gospel of John. Many scholars work from the assumption that Mark is the earliest of the Synoptic Gospels, and so necessarily date the Gospels of Matthew and Luke later than Mark. Robert Lindsey advocated a different understanding of the synoptic relationships, postulating that Luke was the earliest of the three Synoptic Gospels, followed by Mark and then Matthew. For a reassessment of the dates of the Synoptic Gospels from the standpoint of Lindsey’s hypothesis, check out LOY Excursus: The Dates of the Synoptic Gospels on this website.

Rylands Papyrus 𝔓52 (recto). Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

The nature of the relationship between the Gospel of John and the Synoptic Gospels is also a vexing problem. While it was once assumed that the Gospel of John was composed later than the Synoptic Gospels, scholars have begun to consider the possibility that the author of John (like the author of the Didache) may have been acquainted with the sources behind the Synoptic Gospels rather than the Synoptic Gospels themselves. For a discussion of the relationship between John and the Synoptic Gospels, see David Flusser’s article “The Gospel of John’s Jewish-Christian Source” on this website.

It is not even possible to date ancient manuscripts containing the text of the Gospels with absolute certainty. The dates of the early manuscripts are determined on paleographical grounds. This means that the style of writing in a particular manuscript is compared to writing styles found in other ancient documents to arrive at an estimated date of when the manuscript was produced. Precise dating on paleographical grounds is not possible.

- The earliest known manuscript fragments of the Gospel of Matthew are papyri known as 𝔓64(+67) and 𝔓104. Dated to 175-200 C.E., 𝔓64(+67) contains Matt. 3:9, 15; 5:20-22, 25-28; 26:7-8, 10, 14-15, 22-23, 31-33.[1] 𝔓104 is dated to sometime in the second century C.E.[2] It contains Matt. 21:34-37, 43, 45.

- The earliest known manuscript fragment of the Gospel of Mark is papyrus 𝔓137. Scholars date it to the late second to early third century C.E. 𝔓137 contains portions of Mark 1:7-9, 16-18.[3]

- The earliest known manuscript fragment of the Gospel of Luke may be 𝔓4, now regarded as part of 𝔓64(+67), which is dated to 175-200 C.E.[4] 𝔓4 contains Luke 1:58-59; 1:62-2:1, 6-7; 3:8-4:2, 29-32, 34-35; 5:3-8; 5:30-6:16.[5]

- The earliest known manuscript fragment of the Gospel of John is the Rylands Papyrus 𝔓52, which scholars have dated to the mid-second century (125-175) C.E.[6] It contains John 18:31-33, 37-38.

- [1] See Kurt Aland and Barbara Aland, The Text of the New Testament: An Introduction to the Critical Editions and to the Theory and Practice of Modern Textual Criticism (rev. ed.; trans. Erroll F. Rhodes; Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1989), 100; Pasquale Orsini and Willy Clarysse, “Early New Testament Manuscripts and Their Dates: A Critique of Theological Palaeography,” Ephemerides Theologicae Lovaniensis 88.4 (2012): 443-474, esp. 470. ↩

- [2] See Orsini and Clarysse, “Early New Testament Manuscripts and Their Dates: A Critique of Theological Palaeography,” 471. ↩

- [3] See P. J. Parsons and N. Gonis, eds., Oxyrhynchus Papyri LXXXIII (London: Egypt Exploration Society, 2018), 5. ↩

- [4] See Orsini and Clarysse, “Early New Testament Manuscripts and Their Dates: A Critique of Theological Palaeography,” 470. ↩

- [5] Other early witnesses to the Gospel of Luke, such as 𝔓45 (Luke 6:31-7:7; 9:26-14:33), 𝔓69 (Luke 22:41, 45-48, 58-61) and 𝔓75 (Luke 3:18-4:2; 4:34-5:10; 5:37-18:18; 22:4-24:53), are dated to the third century. ↩

- [6] See Aland and Aland, The Text of the New Testament, 99; Orsini and Clarysse, “Early New Testament Manuscripts and Their Dates: A Critique of Theological Palaeography,” 470. ↩

Comments 6

Must scholars eliminate the possibility of divinely predictive prophecy? Why are the choices between post hoc knowledge and commonplace prediction? If the claims made in the gospels are true–is it not possible that the gospel writers preserved a divinely inspired prediction?

Author

Divinely inspired prophecy is a possibility, and certainly Jesus did make predictions that are reflected in the Gospels. But that’s not quite the issue here. The question we’re asking is: Has the way Jesus’ prophecies are presented in the Gospels been shaped by a Gospel writer’s hindsight? Might a Gospel writer, even unconsciously, shaped the wording of a prophecy in light of its fulfillment? If it appears that one Gospel writer has done this, then we are forced to conclude that that particular Gospel was written after the prophesied event.

So, for example, we know that Jesus predicted the destruction of the Temple. If in three Gospels there was simply a prediction “the Temple will be destroyed,” but in a fourth Gospel there is a prediction “the Temple will be destroyed by a Roman named Titus,” we would have good reason for suspecting that that fourth prediction reflected knowledge that came after the prophecy was fulfilled.

In the canonical Gospels there is no “doctoring” of a prophecy that is so blatant, but scholars debate whether some details in some versions of Jesus’ prophecy were added after the Temple was destroyed in light of the events of 70 C.E.

Why is it certain that Paul wrote before Matthew? The Pistis Sophia believes that Thomas, Matthew and Philip were scribes. The three Gospels appear in the Nag Hammadi Scriptures. This implies that someone was writing some of the sayings of Jesus as he said them. What is it that makes it certain that Paul wrote before Matthew?

Author

This much is clear: the author of the Gospel of Matthew was not the same person as Jesus’ disciple Matthew. The disciple Matthew was an eyewitness to the events, the author of the Gospel of Matthew was not an eyewitness, which is why he based his Gospel on one or more written documents (viz., the Gospel of Mark and a lost source also known to the author of Luke). Since the Gospel of Mark was written either shortly before or shortly after the destruction of the Temple, the Gospel of Matthew must have been later still. Paul’s writings, on the other hand, predate the destruction of the Temple.

Does the quotation below refer to the recently found Hebrew manuscript or Greek manuscripts?

“The earliest known manuscript fragments of the Gospel of Matthew are papyri known as 𝔓64(+67) and 𝔓104. Dated to 175-200 C.E., 𝔓64(+67) contains Matt. 3:9, 15; 5:20-22, 25-28; 26:7-8, 10, 14-15, 22-23, 31-33. 𝔓104 is dated to sometime in the second century C.E. It contains Matt. 21:34-37, 43, 45.”

Author

The earliest witnesses to Matthew’s Gospel are Greek papyri. There are no early Hebrew manuscripts of Matthew’s Gospel (see the JP post by David N. Bivin, “Has a Hebrew Gospel Been Found?”). This is because the Gospel of Matthew was composed in Greek. It has been translated at various times and places into Hebrew. This is not to say, however, that some of the sources behind Matthew’s Gospel might not go back to a Hebrew document.

So, to answer your question, the manuscripts referred to in the paragraph you quoted are Greek manuscripts. They are the earliest witnesses to the Gospel of Matthew that have been discovered so far.