How to cite this article:

David N. Bivin and Joshua N. Tilton, “Sign-Seeking Generation,” The Life of Yeshua: A Suggested Reconstruction (Jerusalem Perspective, 2021) [https://www.jerusalemperspective.com/22696/].

Matt. 12:38-40; 16:1-2, 4; Mark 8:11-13;

Luke 11:16, 29-30[1]

Updated: 21 January 2026

[וְהִתְחִיל לוֹמַר] דּוֹר זֶה דּוֹר רָשָׁע הוּא סִימָן הוּא מְבַקֵּשׁ וְסִימָן לֹא יִנָּתֵן לוֹ [אֶלָּא] כְּשֵׁם שֶׁהָיָה יוֹנָה לְאַנְשֵׁי נִינְוֵה לְאוֹת כָּךְ יִהְיֶה בַּר אֱנָשׁ לְדוֹר זֶה

And he began to say, “This generation is a wicked one! It desperately searches for any sign of deliverance, but no such sign will be given to it. Rather, as Yonah was a portent of doom to the inhabitants of Nineveh, so henceforth will the Son of Man be a portent of doom to this generation.[2]

| Table of Contents |

|

3. Conjectured Stages of Transmission 5. Comment 8. Conclusion |

Reconstruction

To view the reconstructed text of Sign-Seeking Generation, click on the link below:

In addition to the reconstruction provided above, we note that Flusser offered his own reconstruction of Luke 11:29, which reads as follows:

הדור הרע הזה מבקש אות ואות לא ינתן לו אלא אות של יונה

This evil generation seeks a sign, but a sign will not be given to it except the sign of Jonah.[3]

Story Placement

In Luke’s Gospel the pericope we have entitled Sign-Seeking Generation (Luke 11:29-30) is sandwiched between A Woman’s Misplaced Blessing (Luke 11:27-28) and Generations That Repented Long Ago (Luke 11:31-32). While there is no obvious connection between Sign-Seeking Generation and A Woman’s Misplaced Blessing, Sign-Seeking Generation and Generations That Repented Long Ago are united by key terms and concepts, namely “this generation,” “Jonah” and “Ninevites.” Despite these common features, it is unlikely that the two pericopae were originally adjacent to one another, for whereas Sign-Seeking Generation deals with signs and the enigmatic figure of the Son of Man, Generations That Repented Long Ago describes eschatological events including the resurrection of the dead and the final judgment.[4] In addition, the goal of Generations That Repented Long Ago is to encourage repentance, whereas repentance plays no more role in Sign-Seeking Generation than it did in Jonah’s proclamation of doom: “Yet forty days and Nineveh will be overturned” (Jonah 3:4). For these reasons it appears that the splicing together of Sign-Seeking Generation with Generations That Repented Long Ago is a secondary development. Most probably, however, this secondary splicing is not the work of the author of Luke, but was already present in his source, since the same arrangement occurs independently of Luke in the Gospel of Matthew (see below).

In the Gospel of Mark Sign-Seeking Generation (Mark 8:11-13) occurs in a section that is otherwise unparalleled in Luke (Mark 6:45-8:21). It appears that with his placement of Sign-Seeking Generation following the Feeding 4,000 episode (Mark 8:1-10) the author of Mark intended to create a sense of irony: despite having miraculously provided the multitudes with bread, the Pharisees wanted Jesus to produce a sign.

Matthew’s Gospel contains two versions of Sign-Seeking Generation. The first (Matt. 12:38-40) agrees with Luke’s placement in as much as it is followed by Generations That Repented Long Ago and occurs in a cluster of Double Tradition (DT) pericopae that is associated in Luke and Matthew with The Finger of God. The table below indicates this cluster with blue lettering:

| Luke | Mark | Matthew |

| Yeshua, His Mother and Brothers (Part 1) (3:20-21) | ||

| The Finger of God (11:14-23) | The Finger of God (3:22-30) | The Finger of God (12:22-32) |

| Fruit of the Heart (12:33-35) | ||

| Giving Account On Judgment Day (12:36-37) | ||

| Sign-Seeking Generation (12:38-40) | ||

| Generations That Repented Long Ago (12:41-42) | ||

| Impure Spirit’s Return (11:24-26) | Impure Spirit’s Return (12:43-45) | |

| A Woman’s Misplaced Blessing (11:27-28) | Yeshua, His Mother and Brothers (Part 2) (3:31-35) | Yeshua, His Mother and Brothers (12:46-50) |

| Sign-Seeking Generation (Luke 11:29-30) | ||

| Generations That Repented Long Ago (Luke 11:31-32) | ||

| Four Soils parable (4:1-9) | Four Soils parable (13:1-9) |

The independent clustering in Luke and Matthew of the pericopae marked in blue is strong evidence that these pericopae were already clustered together in the non-Markan source shared by Luke and Matthew. Probably Luke preserves the pericope order of the common source, whereas the author of Matthew rearranged and supplemented the materials in order to create a minor discourse.[5]

Matthew’s second version of Sign-Seeking Generation (Matt. 16:1-4) agrees with the arrangement in Mark, as we can clearly see in the table below:

| Mark | Matthew |

| Walking on Water (Mark 6:45-52) | Walking on Water (Matt. 14:22-33) |

| Healing at Gennesaret (Mark 6:53-56) | Healing at Gennesaret (Matt. 14:34-36) |

| Handwashing and Purity of Heart (Mark 7:1-23) | Handwashing and Purity of Heart (Matt. 15:1-20) |

| Jesus and a Canaanite Woman (Mark 7:24-30) | Jesus and a Canaanite Woman (Matt. 15:21-28) |

| Ephphatha! (Mark 7:31-37) | Jesus Heals Galileans (Matt. 15:29-31) |

| Feeding 4,000 (Mark 8:1-10) | Feeding 4,000 (Matt. 15:32-39) |

| Sign-Seeking Generation (Mark 8:11-13) | Sign-Seeking Generation (Matt. 16:1-4) |

| Warning About Leaven (Mark 8:14-21) | Warning About Leaven (Matt. 16:5-12) |

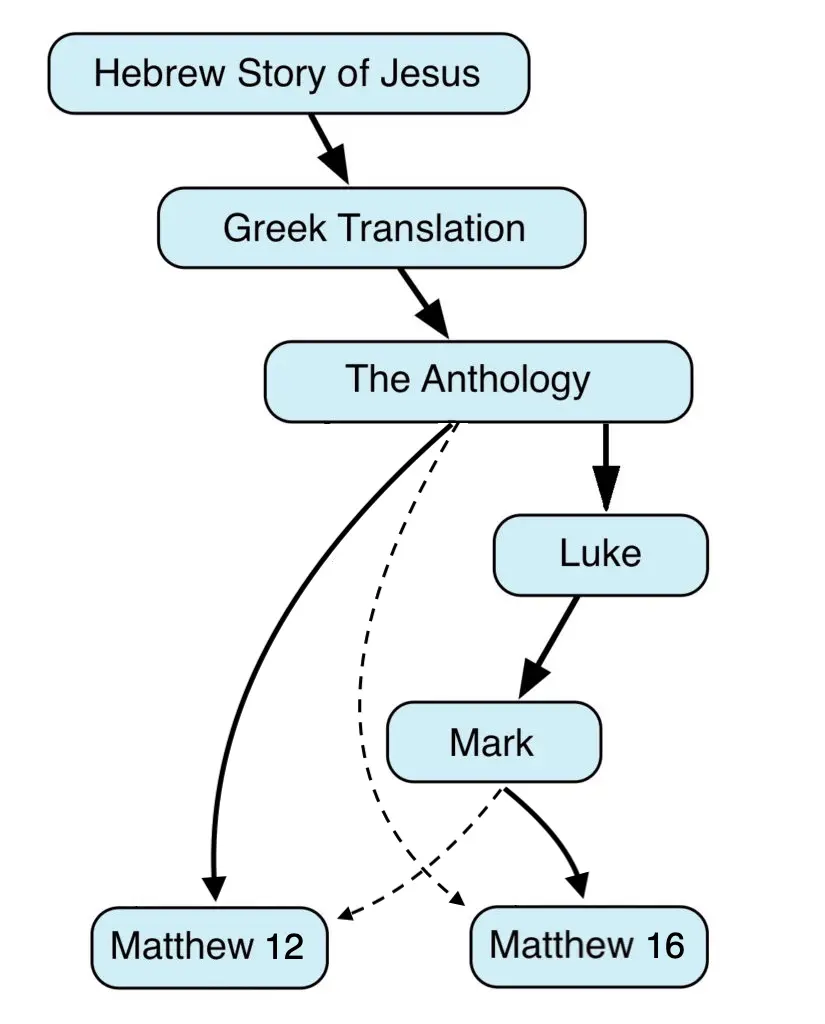

Thus, the doubling of Sign-Seeking Generation in Matthew reflects the arrangement of his two sources, the Anthology (Anth.) and Mark, rather than a historical recollection that a request for a sign was put to Jesus on multiple occasions.[6]

Since none of the Gospels preserve the original setting of Sign-Seeking Generation, we have to ask ourselves where this pericope may have appeared in the Hebrew Life of Yeshua. Our first clue is that Sign-Seeking Generation sounds a note of profound pessimism regarding Jesus’ generation. Whereas his contemporaries sought for hopeful signs that their redemption was near, Jesus insisted that all hopeful signs were mere deceptions: for his generation, which had, on the whole, rejected the Kingdom of Heaven, calamity and turmoil were all they had in store. His generation, which had been seduced by Jewish nationalist fantasies of a victorious militant uprising against the Roman Empire, would search in vain for signs of redemption. Nevertheless, Jesus would himself be a different kind of sign, a portent of doom for the people of Israel. By claiming to be a sign to his generation, Jesus drew on an ancient Jewish tradition according to which certain prophets and holy men were regarded as signs and testimonies against the wickedness that prevailed in their times. The prophet Isaiah and his sons had been given as signs and portents in Israel (Isa. 8:18), Ezekiel had been given as a portent to the house of Israel (Ezek. 12:6), and, in post-biblical Jewish literature, Enoch was made a sign and witness to all generations (Jub. 4:22-24; Sir. 44:16). Apparently, Jesus drew on a tradition according to which Jonah was given as a sign against the wickedness of Nineveh. Accordingly, Jesus claimed that just as Jonah had been a sign of doom to the people of Nineveh, so Jesus would be a sign of doom to his own generation.

In our view, such a pessimistic message fits well into a context in which Jesus foretold judgment against his generation. One of the most stark pronouncements of judgment Jesus made against his generation is found in the pericope we have entitled Innocent Blood (Matt. 23:34-36 ∥ Luke 11:49-51). In that pericope Jesus announced that all the innocent blood that had been poured out on the holy land would be required of his generation. We think Sign-Seeking Generation makes a fitting continuation of Jesus’ speech in Innocent Blood. Therefore, we have included Sign-Seeking Generation in the reconstructed narrative-sayings complex entitled “Choose Repentance or Destruction.” For an overview of the “Choose Repentance or Destruction” complex, click here.

.

.

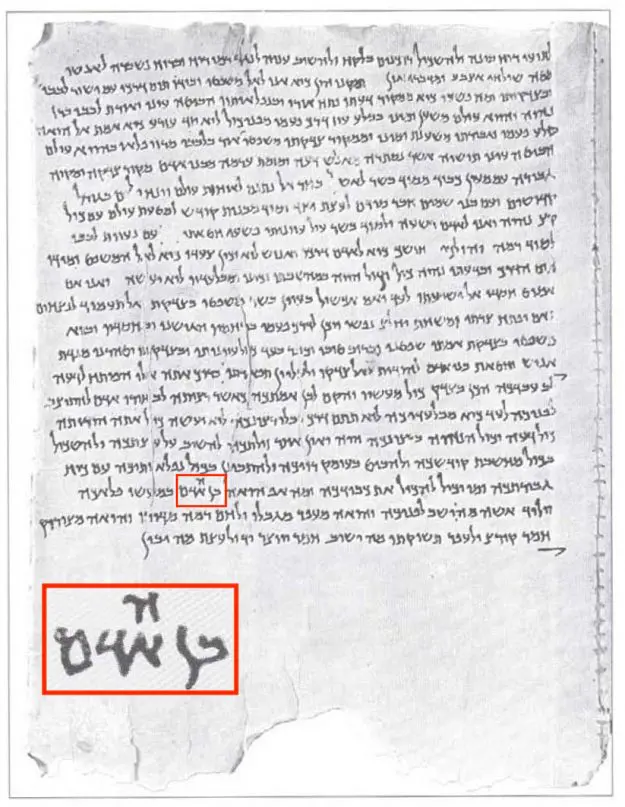

Click here to view the Map of the Conjectured Hebrew Life of Yeshua.

.

.

Conjectured Stages of Transmission

Several factors suggest that the author of Luke copied his version of Sign-Seeking Generation from the more ancient and comprehensive of his literary sources, the Anthology (Anth.). First, as we discussed in the Story Placement discussion above, Sign-Seeking Generation belongs to a pericope cluster common to Luke and Matthew but, apart from Sign-Seeking Generation, unknown to Mark. The clustering in Luke and Matthew of Sign-Seeking Generation together with The Finger of God, Generations That Repented Long Ago and Impure Spirit’s Return suggests that the authors of Luke and Matthew both drew on Anth. for these pericopae.

The substantial Lukan-Matthean minor agreements between Luke 11:29-30 and Matt. 16:1-4 (the second of Matthew’s two versions of Sign-Seeking Generation) are a second indication that Anth. was the origin of Luke’s version of Sign-Seeking Generation. While minor agreements with Matthew do occur when Luke’s source was FR, the quality and quantity of the minor agreements are usually greater when Luke’s source was Anth. Since the Lukan-Matthean minor agreements between Luke 11:29-30 and Matt. 16:1-4 are impressive, it is likely that the author of Luke copied Sign-Seeking Generation from Anth.

A third indication that the author of Luke drew his version of Sign-Seeking Generation from Anth. is the overall ease with which Luke 11:29-30 reverts to Hebrew. Lindsey described Anth. as a highly Hebraic, translation-style Greek source. On the other hand, Lindsey described Luke’s second source, the First Reconstruction (FR), as an epitomized paraphrase of Anth., which by virtue of its stylistic polishing of Anth.’s Greek is somewhat more resistant to Hebrew retroversion. Therefore, ease of Hebrew retroversion can be a useful test for determining from which of Luke’s two sources a pericope is derived.

What we have said about ease of Hebrew retroversion and derivation from Anth. applies to Luke 11:29-30, but not to Luke 11:16. This verse, which the author of Luke inserted into The Finger of God pericope,[7] anticipates Sign-Seeking Generation by explaining that “others were testing Jesus by asking him for a sign from heaven.” It is likely that the author of Luke penned this verse independent of any source for two purposes:

- To give a semblance of unity to the pericope cluster encompassing The Finger of God (Luke 11:14-23), Impure Spirit’s Return (Luke 11:24-26), A Woman’s Misplaced Blessing (Luke 11:27-28), Sign-Seeking Generation (Luke 11:29-30) and Generations That Repented Long Ago (Luke 11:31-32), which the author of Luke incorporated from Anth.[8]

- To attempt to explain what Jesus meant by declaring that his generation sought for a sign.

In the second of these two purposes the author of Luke failed, at least in terms of historical accuracy. The author of Luke misunderstood the sign-seeking Jesus referred to, assuming that Jesus’ generation wanted some miracle that would authenticate his messianic claims. However, Jesus was quite reticent regarding his role within the divine economy. Despite expressing an exalted self-awareness, Jesus rarely attempted to precisely define or label his unique status, preferring instead to redirect people’s attention to manifestations of the Kingdom of Heaven and away from speculations about himself.[9] It is unlikely, therefore, that Jesus’ activity or teaching would have provoked a demand for proof of his messianic status, since his messiahship was neither the focus of his action nor the content of his message.[10]

Flusser suggested a far more plausible background for the search for signs conducted by Jesus’ generation: they sought not for miracles to authenticate Jesus’ messianic status but for any sign that liberation from Roman domination was near.[11] Josephus documented the appearance in the first century C.E. of several would-be prophets of redemption who promised various signs of deliverance from Roman imperial rule. During the governorship of Fadus (44-46 C.E.), Theudas, a self-proclaimed prophet, declared that at his command the Jordan River would part (Ant. 20:97-98; cf. Acts 5:36), evidently a sign that would inaugurate a reconquest of the Holy Land—this time against the Romans—as in the days of Joshua, who successfully led the Israelite campaign against the Canaanites.[12] Josephus also described prophets with similar aims who arose during Felix’s tenure as governor of Judea (52-60 C.E):

πλάνοι γὰρ ἄνθρωποι καὶ ἀπατεῶνες, [ὑπὸ] προσχήματι θειασμοῦ νεωτερισμοὺς καὶ μεταβολὰς πραγματευόμενοι, δαιμονᾶν τὸ πλῆθος ἔπειθον καὶ προῆγον εἰς τὴν ἐρημίαν, ὡς ἐκεῖ τοῦ θεοῦ δείξοντος αὐτοῖς σημεῖα ἐλευθερίας. ἐπὶ τούτοις Φῆλιξ, ἐδόκει γὰρ ἀποστάσεως εἶναι καταβολή, πέμψας ἱππεῖς καὶ πεζοὺς ὁπλίτας πολὺ πλῆθος διέφθειρεν.

Deceivers and impostors, under the pretence of divine inspiration fostering revolutionary changes, they persuaded the multitude to act like madmen, and led them out into the desert under the belief that God would there give them signs of deliverance [σημεῖα ἐλευθερίας]. Against them Felix, regarding this as but the preliminary to insurrection, sent a body of cavalry and heavy-armed infantry, and put a large number to the sword. (J.W. 2:259-260; Loeb, adapted; cf. Ant. 20:167-168)

One of the sign-producing prophets who arose during the governorship of Felix was a Jew of Egyptian extraction who collected a following on the Mount of Olives and promised that the walls of Jerusalem would spontaneously crumble at his command—in a manner reminiscent of the walls of Jericho[13] —in order to allow his entourage to recapture the holy city from the Romans (Ant. 20:169-172; cf. Acts 21:38).

Josephus also described a prophet who promised signs of deliverance in 70 C.E., even as the Temple was engulfed in flames:

ἧκον δὲ καὶ ἐπὶ τὴν λοιπὴν στοὰν τοῦ ἔξωθεν ἱεροῦ· καταφεύγει δ᾿ ἐπ᾿ αὐτὴν ἀπὸ τοῦ δήμου γύναια καὶ παιδία καὶ σύμμικτος ὄχλος εἰς ἑξακισχιλίους. πρὶν δὲ Καίσαρα κρῖναί τι περὶ αὐτῶν ἢ κελεῦσαι τοὺς ἡγεμόνας, φερόμενοι τοῖς θυμοῖς οἱ στρατιῶται τὴν στοὰν ὑφάπτουσι, καὶ συνέβη τοὺς μὲν ῥιπτοῦντας αὑτοὺς ἐκ τῆς φλογὸς διαφθαρῆναι, τοὺς δὲ ἐν αὐτῇ· περιεσώθη δὲ ἐκ τοσούτων οὐδείς. τούτοις αἴτιος τῆς ἀπωλείας ψευδοπροφήτης τις κατέστη κατ᾿ ἐκείνην κηρύξας τὴν ἡμέραν τοῖς ἐπὶ τῆς πόλεως, ὡς ὁ θεὸς ἐπὶ τὸ ἱερὸν ἀναβῆναι κελεύει δεξομένους τὰ σημεῖα τῆς σωτηρίας. πολλοὶ δ᾿ ἦσαν ἐγκάθετοι παρὰ τῶν τυράννων τότε πρὸς τὸν δῆμον προφῆται προσμένειν τὴν ἀπὸ τοῦ θεοῦ βοήθειαν καταγγέλλοντες, ὡς ἧττον αὐτομολοῖεν καὶ τοὺς ἐπάνω δέους καὶ φυλακῆς γενομένους ἐλπὶς παρακροτοίη.

They [i.e., the Roman soldiers destroying the Temple—DNB and JNT] then proceeded to the one remaining portico of the outer court, on which the poor women and children of the populace and a mixed multitude had taken refuge, numbering six thousand. And before Caesar had come to any decision or given any orders to the officers concerning these people, the soldiers, carried away by rage, set fire to the portico from below; with the result that some were killed plunging out of the flames, others perished amidst them, and out of all that multitude not a soul escaped. They owed their destruction to a false prophet, who had on that day proclaimed to the people in the city that God commanded them to go up to the temple court, to receive there signs of their deliverance [τὰ σημεῖα τῆς σωτηρίας]. Numerous prophets, indeed, were at this period suborned by the tyrants to delude the people, by bidding them await help from God, in order that desertions might be checked and that those who were above fear and precaution might be encouraged by hope. (J.W. 6:283-286; Loeb, adapted)

The credence given to these sign-producing prophets despite repeated disappointments is a testimony to how desperately the Jewish populace yearned for deliverance from Roman rule. It is also a testament to their deep-seated conviction that militant action would be the catalyst for divine intervention.

Although the sign-producing prophets mentioned in Josephus’ works were active in the period following Jesus’ crucifixion, it is highly probable that there were precursors to these individuals who were active in Jesus’ lifetime and, perhaps, even earlier. Moreover, these prophets of liberation were certainly tapping into preexisting popular conceptions concerning Israel’s future redemption. They did not need to convince the populace of their vision of redemption, as Jesus had to do with his, they merely needed to convince their followers that the moment of redemption had finally arrived. By contrast, not only was Jesus’ vision of the redemption different from the majority of his contemporaries, the means by which he believed Israel’s redemption would be achieved were beyond the pale of normal expectations. For these reasons Jesus’ redemptive mission met with limited success.

Ironically, earlier in his career Jesus had proclaimed that the influence of foreign dominions and evil powers was retreating in the face of the Kingdom of Heaven.[14] But Jesus’ proclamation of the Kingdom of Heaven demanded that his generation give up aspirations of military victory and the lust for revenge, urging, to the contrary, that redemption would be achieved as acts of mercy and forgiveness, love for enemies and peacemaking unleashed the re-creative power of the Holy Spirit. In the political climate of rising militant Jewish nationalism, Jesus’ demand was, by and large, rejected by his generation, and eventually Jesus concluded that the opportunity for Israel’s redemption had passed. Deliverance from imperial domination was no longer in the cards for Israel, rather Jesus’ generation would be subjected to punishment in the short term and condemnation in the eschatological future because they had refused to repent of their violent nationalistic tendencies and embrace the Kingdom of Heaven. Thus, according to Jesus, the only authentic signs that would be forthcoming to his generation would be portents of doom.

The sentiment Jesus expressed in Sign-Seeking Generation is remarkably similar to a statement attributed to Rabbi Simon bar Menasya:

א″ר סימון בר מנסיא אין ישראל רואין סימן גאולה לעולם עד שיחזרו ויבקשו שלשתם, הדא הוא דכתיב אחר ישובו בני ישראל ובקשו את ה′ אלהיהם זו מלכות שמים, ואת דוד מלכם זו מלכות בית דוד, ופחדו אל ה′ ואל טובו זה בית המקדש

Rabbi Simon bar Menasya said, “Israel will never see a sign of redemption [סִימַן גְּאוּלָּה] until it returns and seeks these three: the first is as it is written, Afterward the children of Israel will return and seek the LORD their God [Hos. 3:5]—this is the Kingdom of Heaven—and David their king [ibid.]—this is the kingdom of the House of David—and they will have respect for the LORD and his goodness [ibid.]—this is the Temple.” (Yalkut Shim‘oni §106)

Like Jesus, Rabbi Simon bar Menasya—a member of the Holy Congregation in Jerusalem, which existed in the late second century C.E.[15] —believed that no signs of redemption would be forthcoming so long as Israel failed to repent and seek the Kingdom of Heaven.[16]

Unfortunately, the author of Luke’s mistaken assumption that Jesus’ generation demanded divine confirmation of Jesus’ messianic claims had far-reaching consequences for the synoptic tradition. The author of Mark picked up this notion from Luke and incorporated it into his narrative introduction to Sign-Seeking Generation (Mark 8:11). In turn, Mark’s version of Sign-Seeking Generation influenced both versions of this pericope in Matthew.

It is clear from its placement in association with The Finger of God pericope cluster found in Luke and Matthew that the Matt. 12:38-40 version of Sign-Seeking Generation depends on Anth. It is equally clear from the placement of the Matt. 16:1-4 version of Sign-Seeking Generation in a series of pericopae paralleled in Mark but absent from Luke that this second version depends on Mark.[17] Nevertheless, a considerable degree of cross-pollination between the two Matthean versions has resulted in very similar wording in the two versions. The narrative introductions to both versions depend on Mark 8:11, whereas Jesus’ speech in both versions depends on Anth., as is shown by the numerous agreements with Luke against Mark in Matt. 16:4.[18] Cross-pollination between Matthean doublets and parallels is a redactional feature we have observed elsewhere in Matthew’s Gospel.[19]

In the writings of Justin Martyr we find a quotation of Sign-Seeking Generation that seems to betray the influence of all four canonical versions (Dial. §107).[20]

Crucial Issues

- What is “the sign of Jonah”?

- What is the meaning of “Son of Man” in Sign-Seeking Generation?

Comment

L1-24 As we stated in the Conjectured Stages of Transmission discussion above, we regard Luke 11:16 as a redactional addition to The Finger of God pericope which the author of Luke composed in order to create a sense of unity between The Finger of God, Sign-Seeking Generation and the intervening materials, and also to explain to his readers what he thought was meant when Jesus claimed his generation was seeking a sign. The author of Mark incorporated a paraphrase of Luke 11:16 into his narrative introduction to Sign-Seeking Generation (Mark 8:11), and the author of Matthew relied on Mark 8:11 for his introductions to both of his versions of Sign-Seeking Generation. Thus, none of the narrative introductions to Sign-Seeking Generation can be traced back to a pre-synoptic source.[21] In Anth., Sign-Seeking Generation probably lacked any kind of introduction or explanation,[22] which accounts for the author of Luke’s need to create one and for the author of Matthew’s reliance on Mark 8:11 to provide an introduction to his Anth. version of Sign-Seeking Generation.[23]

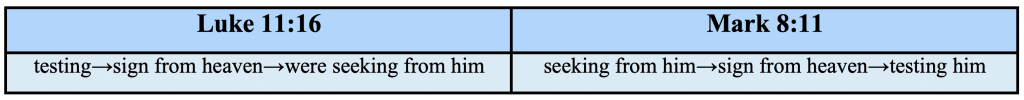

L1-4 As we already have had occasion to note, we believe Luke 11:16, which appears in The Finger of God pericope and lays the groundwork for Sign-Seeking Generation, was composed by the author of Luke without the aid of an underlying source. Several indications lead us to this conclusion. First, the word order of Luke 11:16 is distinctly un-Hebraic, as we can see from a comparison of the Greek text with Delitzsch’s Hebrew translation:

| Luke 11:16 | Delitzsch’s Translation |

| ἕτεροι δὲ | וְיֵשׁ אֲשֶׁר |

| others / But | And there are / which |

| πειράζοντες | נִסּוּהוּ |

| testing | they tested him |

| σημεῖον | |

| a sign | |

| ἐξ οὐρανοῦ | |

| from / heaven | |

| ἐζήτουν | וַיִּשְׁאֲלוּ |

| were seeking | and they asked |

| παρ᾿ αὐτοῦ | מִמֶּנּוּ |

| from / him. | from him |

| אוֹת | |

| a sign | |

| מִן הַשָּׁמָיִם | |

| from / the heavens. |

Second, the author’s vague use of ἕτεροι (heteroi, “others”) to describe the persons who were testing Jesus suggests that the author of Luke did not know, and did not wish to guess, the identity of those who were seeking a sign. From Anth. the author of Luke could have learned only that Jesus’ generation sought for a sign, but the author of Luke could hardly write in Luke 11:16 that Jesus’ entire generation tested him, especially since the author of Luke was at pains to show in his Gospel and Acts that there were many who were sympathetic to Jesus and his teachings. Moreover, the use of otherwise unspecified “others” appears to be one of the author of Luke’s redactional reflexes;[24] it occurs in Luke 8:3 (unique); 10:1 (redactional);[25] 11:16; Acts 2:13; 15:35; 17:34.[26]

Third, it can be no accident that there are only two instances of the verb πειράζειν (peirazein, “to test,” “to tempt”) in Luke’s Gospel. The first occurs in Yeshua’s Testing (Luke 4:2), where the devil tempts Jesus to prove his messianic status by performing certain miracles. The only other instance of πειράζειν occurs in Luke 11:16, where the author of Luke explains that certain persons wanted Jesus to produce a sign. The restriction of πειράζειν in Luke’s Gospel to these two passages gives every impression of editorial cross-referencing intended to direct readers to interpret the sign-seeking of Jesus’ generation as a diabolical temptation to produce miraculous proofs of his messianic status.[27]

The author of Luke’s editorial framing in Luke 11:16 of sign-seeking as temptation (L2) and his redactional clarification that the sign being sought was to be produced by Jesus (L4) from heaven (L3), like a magician pulling a rabbit out of his hat, had an outsized influence on the synoptic tradition. Not only did Luke 11:16 obscure the original meaning of the sign-seeking Jesus disparaged (on which, see the Conjectured Stages of Transmission discussion above), which obfuscation was unwittingly passed along to Mark, and via Mark to Matthew, Luke 11:16 also appears to be the genesis of the notion that certain of Jesus’ opponents used to test or tempt him. In Luke’s Gospel this concept only occurs in Luke 11:16, but in Mark it occurs in Sign-Seeking Generation (Mark 8:11), Divorce (Mark 10:2) and Tribute to Caesar (Mark 12:15).[28] Each of these instances of temptation were picked up by the author of Matthew (Matt. 16:1 [Sign-Seeking Generation]; 19:3 [Divorce]; 22:18 [Tribute to Caesar]), who also expanded the temptation motif to the question concerning the greatest commandment (Matt. 22:35).

It is also possible that Luke 11:16 influenced the Gospel of Mark in another way. Luke 11:16 prepares for Sign-Seeking Generation by adding to The Finger of God a second challenge to the main accusation that it was by alliance with the prince of demons that Jesus exorcised lesser demons (Luke 11:15). This double challenge, in which one is addressed in the immediate context and the other is postponed, is paralleled in Mark 3:21-22, in which two accusations against Jesus are articulated: the first (“He is out of his mind!”) by Jesus’ family members (Mark 3:21), the second (“By the prince of demons he drives out demons”) by scribes from Jerusalem (Mark 3:22). In Mark the second accusation is addressed immediately (Mark 3:22-30), while the first accusation explains Jesus’ chilly reception of his mother and brothers (Mark 3:31-35). It seems likely, therefore, that Luke’s foreshadowing of Sign-Seeking Generation in The Finger of God provided the author of Mark with a model for the two-part narration of Yeshua, His Mother and Brothers.[29] This possibility becomes even more probable when we compare the ordering of pericopae involving The Finger of God in Luke and Mark:

| Luke | Mark |

| The Finger of God (Luke 11:14-15) | |

| Sign-Seeking Generation preview (Luke 11:16) | Yeshua, His Mother and Brothers (Part 1) (Mark 3:20-21) |

| The Finger of God continued (Luke 11:17-23) | Prince of Demons Accusation (Mark 3:22) |

| The Finger of God (Mark 3:23-30) | |

| Impure Spirit’s Return (Luke 11:24-26) | [omitted] |

| A Woman’s Misplaced Blessing (Luke 11:27-28) | Yeshua, His Mother and Brothers (Part 2) (Mark 3:31-35) |

| Sign-Seeking Generation (Luke 11:29-30) | [omitted] |

The author of Mark did not want to foreshadow the Sign-Seeking Generation pericope, which he intended to omit. He therefore transferred the foreshadowing technique he observed in Luke 11:16 to Yeshua, His Mother and Brothers, which the author of Mark adopted in lieu of A Woman’s Misplaced Blessing.

L6-7 τῶν δὲ ὄχλων ἐπαθροιζομένων (Luke 11:29). As with Luke 11:16, we suspect that the author of Luke independently composed the narrative (re)introduction to Sign-Seeking Generation in L6-7. The genitive absolute construction τῶν δὲ ὄχλων ἐπαθροιζομένων (tōn de ochlōn epathroizomenōn, “as the crowds increased”) is certainly un-Hebraic, and the use of genitives absolute is typical of Lukan redaction.[30] In addition, the use of the verb ἀθροίζεσθαι (athroizesthai, “to gather”; Luke 24:33) and compounds thereof (ἐπαθροίζεσθαι [epathroizesthai, “to converge upon”; Luke 11:29] and συναθροίζεσθαι [sūnathroizesthai, “to converge”; Acts 12:12; 19:25]), which belong to a higher register of Greek than is typical of Anth. or even FR, occurs in the writings of Luke but not in the other Synoptic Gospels, nor indeed anywhere else in NT. Thus, the presence of ἐπαθροίζεσθαι in Luke 11:29 is best attributed to Lukan redaction.[31]

L8-9 τότε ἀπεκρίθησαν αὐτῷ (Matt. 12:38). In Matthew’s first version of Sign-Seeking Generation the demand for a sign comes in answer to a minor discourse (Matt. 12:25-37) in which Jesus refutes the charge that it was only because he was in league with the prince of demons that he was able to drive out lesser demons. By transforming the request for a sign into a response to Jesus’ discourse, the author of Matthew succeeded in integrating Sign-Seeking Generation more fully into its context. However, Matthew’s wording in L8-9 is redactional. The narrative τότε (tote, “then”) with which Matt. 12:38 opens is typically Matthean,[32] and although ἀπεκρίθησαν…λέγοντες (apekrithēsan…legontes, “they answered…saying”; L8, L13) in Matt. 12:38 can be reconstructed easily as וַיַּעֲנוּ…לֵאמֹר (vaya‘anū…lē’mor, “and they answered…saying”; cf. Gen. 23:5), we have found that the author of Matthew was capable of using ἀποκρίνειν…λέγειν/εἰπεῖν in redactional material.[33]

L8 καὶ ἐξῆλθον (Mark 8:11). The going out of the Pharisees to meet Jesus in Mark 8:11 is a redactional bridge that unites Mark’s version of Sign-Seeking Generation to the preceding Feeding 4,000 pericope (Mark 8:1-10). Matthew’s καὶ προσελθόντες (kai proselthontes, “and approaching”) in Matt. 16:1 is simply a redactional paraphrase of καὶ ἐξῆλθον (kai exēlthon, “and they went out”) in Mark 8:11.

L10 τινες τῶν γραμματέων (Matt. 12:38). In the first of Matthew’s two versions of Sign-Seeking Generation Jesus’ opponents are identified as the scribes (L10) and Pharisees (L11). The addition of scribes, which is unparalleled in Mark 8:11, may be due to the author of Matthew’s recollection that in The Finger of God pericope Mark’s Gospel had attributed the accusation leveled against Jesus to the scribes (Mark 3:22), whereas Matthew had attributed the same accusation to the Pharisees (Matt. 12:24). Thus, by adding the scribes to the list of those who tested Jesus, the author of Matthew was able to compensate for his earlier omission of the same.[34]

L11 οἱ Φαρεισαῖοι (Mark 8:11). The author of Mark identified the sign-seekers, who remain anonymous in Luke, as the Pharisees. This identification was subsequently taken up by the author of Matthew in both his versions of Sign-Seeking Generation.[35] What was it that caused the author of Mark to think that it was the Pharisees who demanded a sign? It may have been the series of woes against the Pharisees recorded in Luke 11:37-54 that suggested this identification to him. These anti-Pharisaic polemics in Luke occur in close proximity to Sign-Seeking Generation (Luke 11:29-30), and the author of Mark easily could have assumed that this proximity of these polemics revealed the identity of the anonymous sign-seekers in Luke.

Following the woes against the Pharisees in Luke 11:37-54, the author of Luke recorded a saying of Jesus in which he warns his disciples against the leaven of the Pharisees, which is hypocrisy (Luke 12:1). The author of Mark, who skipped over Luke’s series of woes against the Pharisees, made Jesus’ warning about “leaven” his sequel to the Sign-Seeking Generation pericope. However, the author of Mark made significant changes to Jesus’ warning: in Mark the “leaven” is no longer hypocrisy, and reference is made to the leaven of Herod as well as to the leaven of the Pharisees. These two changes are undoubtedly related.

From the information that can be gleaned about the Pharisees and Herod in the Gospel of Mark, it is difficult to determine what “leaven” the Pharisees could have had in common with Herod, especially since Herod is nowhere accused of hypocrisy. If we turn to the Gospel of Luke, however, we find that Herod Antipas had long desired to see Jesus perform some miracle, but when he finally met Jesus in person he was disappointed (Luke 23:8). Antipas’ unsatisfied desire for wonder-working is parallel to the denial of a sign to the Pharisees in Mark’s version of Sign-Seeking Generation.

Identifying sign-seeking as the leaven of the Pharisees and Herod in Mark 8:15 helps make sense of the pericope arrangement in Mark 8 (Feeding 4,000→Sign-Seeking Generation→Warning About Leaven): despite Jesus’ having miraculously provided the crowds with bread, the Pharisees demand a sign. Jesus denies their request, reasoning that if the Pharisees are unwilling to believe the evidence right before their eyes, no sign from heaven will be able to convince them of the truth. Jesus then warns his disciples against the “leaven” of sign-seeking, but they think Jesus is talking about their failure to bring bread with them in the boat. Their stupidity reveals that even the disciples had failed to understand the significance of the miracles that were happening right before their eyes.[36]

If this analysis is correct, it shows how heavily the author of Mark depended on the Gospel of Luke. It also reveals that Mark’s Gospel is such a creative reworking of Lukan materials that it can be of very little use in reconstructing the Hebrew Life of Yeshua.

L12 καὶ Σαδδουκαῖοι (Matt. 16:1). Whereas in Matthew’s first version of Sign-Seeking Generation the scribes and Pharisees are the sign-seekers, in Matthew’s second version the sign-seekers are the Pharisees and Sadducees. Not only is an alliance of Pharisees and Sadducees historically improbable,[37] the combination is unique among the synoptics to the Gospel of Matthew[38] and appears to reflect the author of Matthew’s desire for Jesus’ experience to reflect that of John the Baptist.[39] In Yohanan the Immerser Demands Repentance the author of Matthew had portrayed the Pharisees and Sadducees as a united front against John the Baptist (Matt. 3:7),[40] so here he unites the Pharisees and Sadducees in their plot to test Jesus.[41]

L13 [καὶ ἤρξατο (GR). Since the use of ἄρχειν + infinitive is not typical of Lukan redaction,[42] it may be that its presence in Luke 11:29 (L13, L24) is a reflection of a pre-synoptic source (Anth.). We have therefore tentatively accepted Luke’s ἤρξατο (ērxato, “he began”) for GR in L13, but we have placed this part of the reconstruction within brackets to indicate our uncertainty. We have also introduced Luke’s verb with the conjunction καί (kai, “and”) on the assumption that the author of Luke omitted this conjunction when he inserted the genitive absolute in L6-7.

וְהִתְחִיל] (HR). On reconstructing ἄρχειν + λέγειν—the infinitive λέγειν (legein, “to say”) appears in L24—with הִתְחִיל לוֹמַר (hitḥil lōmar, “he began to say”), see Yeshua’s Words about Yohanan the Immerser, Comment to L4.

ἤρξαντο συνζητεῖν αὐτῷ (Mark 8:11). The author of Mark took over the ἄρχειν + infinitive construction from Luke (L13, L24), but he changed the subject from Jesus (3rd sing.) to the Pharisees (3rd plur.). Mark’s is the only version of Sign-Seeking Generation to include the verb συζητεῖν (sūzētein, “to discuss,” “to argue”). Neither Luke nor Matthew ever support Mark’s use of this verb,[43] despite the author of Luke’s willingness to use συζητεῖν elsewhere in his writings (Luke 22:23; 24:15; Acts 6:9; 9:29). The Lukan-Matthean agreement against Mark’s use of this verb in Sign-Seeking Generation is a good indication that it did not occur in Anth.

It may be that the author of Mark’s use of συζητεῖν is an example of what Lindsey called a “Markan pick-up,” in other words, vocabulary the author of Mark picked up from the writings of Luke and sprinkled throughout his Gospel.[44] Mark’s use of συζητεῖν in Sign-Seeking Generation certainly resembles Luke’s use of the same verb in Betrayal Foretold:

| Mark 8:11 | Luke 22:23 |

| καὶ ἐξῆλθον οἱ Φαρισαῖοι καὶ ἤρξαντο συζητεῖν αὐτῷ, ζητοῦντες παρ᾿ αὐτοῦ σημεῖον ἀπὸ τοῦ οὐρανοῦ, πειράζοντες αὐτόν. | καὶ αὐτοὶ ἤρξαντο συζητεῖν πρὸς ἑαυτοὺς τὸ τίς ἄρα εἴη ἐξ αὐτῶν ὁ τοῦτο μέλλων πράσσειν |

| And the Pharisees went out and began to argue with him, seeking from him a sign from heaven, testing him. | And they began to argue with one another who of them it might be that was going to do this. |

L14 διδάσκαλε (Matt. 12:38). The first of Matthew’s two versions of Sign-Seeking Generation is the only one of the four synoptic versions in which the request for a sign is put into direct speech. The request begins with the scribes and Pharisees addressing Jesus as διδάσκαλε (didaskale, “teacher”). Gundry regarded the addition of διδάσκαλε as characteristically Matthean,[45] however we cannot substantiate this claim. The vocative διδάσκαλε occurs 6xx in Matthew (Matt. 8:19; 12:38; 19:16; 22:16; 22:24; 22:36), but only twice without the agreement of Luke and/or Mark (Matt. 8:19; 12:38).[46]

Flusser, being impressed by a rabbinic story in which the disciples of Rabbi Yose ben Kisma say to him, רבינו תן לנו אות (“Our master, give us a sign!”; b. Sanh. 98a), regarded the request in Matt. 12:38 as original,[47] but there are important differences between the request in Matt. 12:38 and that in b. Sanh. 98a. In the first place, the request in Matt. 12:38 comes from Jesus’ opponents, whereas the request in b. Sanh. 98a comes from Rabbi Yose ben Kisma’s disciples. In the second place, the request for a sign in b. Sanh. 98a is a direct response to Rabbi Yose ben Kisma’s prediction about the future, whereas in Matt. 12:38 there is no logical connection between the demand for a sign and the discourse that preceded it. Moreover, as Matthew tells the story, Jesus’ response is disproportionate to the request. For whereas the request for a sign comes from a discrete group of scribes and Pharisees, Jesus’ denial is addressed to his entire generation.[48] The discrepancy between the limited group making the request and the much wider target of Jesus’ condemnation suggests that the former (viz., the group making the request) is an editorial addition to the original saying.[49] There is another way in which Jesus’ response does not match the request: whereas the scribes and Pharisees want a sign from Jesus, Jesus replies that no sign will be forthcoming from anyone. This discrepancy, too, reinforces the impression that the request is an editorial addition to the original saying. Finally, the word order of the request in Matt. 12:38 is un-Hebraic,[50] which suggests that it did not come from Matthew’s source. However, the request does resemble the request of James and John as reported in Mark 10:35:

| Matt. 12:38 | Mark 10:35 |

| διδάσκαλε | διδάσκαλε |

| Teacher | Teacher |

| θέλομεν | θέλομεν |

| we want | we want |

| ἀπὸ σοῦ | ἵνα |

| from you | that |

| σημεῖον | ὃ ἐὰν αἰτήσωμέν σε |

| a sign | whatever we might ask you |

| ἰδεῖν | ποιήσῃς ἡμῖν |

| to see. | you might do for us. |

Thus, despite the rabbinic parallel, we cannot agree with Flusser’s assessment that Matt. 12:38 preserves the original form of the request for a sign.[51]

L15 πειράζοντες (Matt. 16:1). The reference to “testing” in Matthew’s second version of Sign-Seeking Generation echoes Mark 8:11 (L20), which in turn derives from Luke 11:16 (L2).

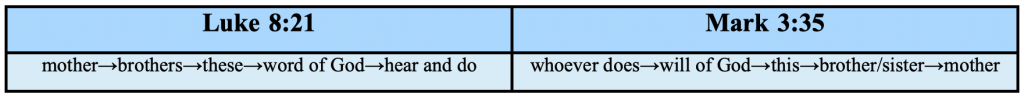

L16-20 Not only does Mark’s wording in L16-20 echo Luke’s in L2-4, the two are almost perfect mirror images of one another:

We encountered similar mirroring of a sentence in Luke in Yeshua, His Mother and Brothers:

Thus, mirror imaging appears to be a trait of Markan redaction.[52]

L16 ἐπηρώτησαν αὐτὸν (Matt. 16:1). Matthew’s ἐπηρώτησαν αὐτόν (epērōtēsan avton, “they asked him”) is a stylistic improvement over Mark’s ζητοῦντες παρ᾿ αὐτοῦ (zētountes par avtou, “seeking from him”). Mark’s wording echoes Luke 11:16 (L4), which merely reflects Jesus’ statement that his generation σημεῖον ζητεῖ (sēmeion zētei, “seeks a sign”; L29). As we discussed in the Conjectured Stages of Transmission section above, the author of Luke composed Luke 11:16 in order to explain what he thought Jesus meant by declaring that his generation sought a sign.

L17-18 σημεῖον ἀπὸ τοῦ οὐρανοῦ (Mark 8:11). Mark’s σημεῖον ἀπὸ τοῦ οὐρανοῦ (sēmeion apo tou ouranou, “sign from the heaven”) echoes Luke’s σημεῖον ἐξ οὐρανοῦ (sēmeion ex ouranou, “sign from heaven”; Luke 11:16).[53] The parallel in Matt. 12:38 omits “from heaven,” while in Matt. 16:1 the author of Matthew wrote ἐκ τοῦ οὐρανοῦ (ek tou ouranou, “from the heaven”). Matthew’s ἐκ (“from”) in L18 thus forms a minor agreement with Luke’s ἐξ (“from”) in L3. It is extremely doubtful, however, that this particular minor agreement points to an underlying narrative introduction to Sign-Seeking Generation in Anth. It is more likely that the agreement is simply an accidental result of Matthew’s paraphrasing of Mark 8:11. The author of Matthew probably preferred ἐκ (“from,” “out of”) to Mark’s ἀπό (“from”) because it made for a better connection to Interpreting the Time (Matt. 16:2b-3)—“a sign out of [ἐκ] the sky” fits better with the meteorological phenomena discussed in Matt. 16:2b-3 than “a sign originating from [ἀπό] heaven”—which the author of Matthew inserted into his second version of Sign-Seeking Generation.

L19 ἰδεῖν (Matt. 12:38) / ἐπιδεῖξαι αὐτοῖς (Matt. 16:1). The addition of ἰδεῖν (idein, “to see”) in Matt. 12:38 and ἐπιδεῖξαι αὐτοῖς (epideixai avtois, “to show them”) in Matt. 16:1 sharpens the demand for a sign in a way that is not as clear in the Markan or Lukan versions of Sign-Seeking Generation.[54] The greater specificity in Matthew’s two versions is a literary improvement, but also an indication of his greater remove from the original intention of Jesus’ saying, in which Jesus’ generation sought for signs of deliverance, but not necessarily from Jesus himself, let alone proofs of Jesus’ messianic status.

L21-22 καὶ ἀναστενάξας τῷ πνεύματι αὐτοῦ (Mark 8:12). The groaning of Jesus in his spirit that Mark 8:12 describes is absent in the Lukan and Matthean parallels,[55] a good indication that no such action was reported in Anth. However, Jesus’ groaning in the spirit reminds us of the following passage in Romans:

οἴδαμεν γὰρ ὅτι πᾶσα ἡ κτίσις συστενάζει καὶ συνωδίνει ἄχρι τοῦ νῦν· οὐ μόνον δέ, ἀλλὰ καὶ αὐτοὶ τὴν ἀπαρχὴν τοῦ πνεύματος ἔχοντες, ἡμεῖς καὶ αὐτοὶ ἐν ἑαυτοῖς στενάζομεν υἱοθεσίαν ἀπεκδεχόμενοι, τὴν ἀπολύτρωσιν τοῦ σώματος ἡμῶν.

For we know that all the creation groans together [συστενάζει] and suffers together until now. And not it alone, but those having the firstfruits of the Sprit [τοῦ πνεύματος], we also in ourselves groan [ἐν ἑαυτοῖς στενάζομεν] while awaiting adoption, the redemption of our bodies. (Rom. 8:22-23)

Might the author of Mark have wished to allude to these verses? Lindsey believed that the author of Mark frequently worked allusions to the Pauline epistles into his Gospel.[56] What is more, there might be a very good reason for the author of Mark to have alluded to this passage, since in the verses that follow Rom. 8:22-23 we read this:

τῇ γὰρ ἐλπίδι ἐσώθημεν· ἐλπὶς δὲ βλεπομένη οὐκ ἔστιν ἐλπίς· ὃ γὰρ βλέπει τίς ἐλπίζει; εἰ δὲ ὃ οὐ βλέπομεν ἐλπίζομεν, δι᾿ ὑπομονῆς ἀπεκδεχόμεθα

For with the hope [i.e., of redemption—DNB and JNT] we were saved. But hope that is seen is not hope. For who hopes for what he sees? But if we hope for what we do not see, we await it with patience. (Rom. 8:24-25)

The author of Mark may have felt that this passage in Romans was an apt commentary on the demand for a sign. In the author of Mark’s opinion, the demand for a sign was a display of impatience and lack of hopeful trust in God. Those who demanded a sign from Jesus had cut themselves off from the Spirit and alienated themselves from the suffering common to the rest of creation.[57] By portraying Jesus’ spiritual groaning, the author of Mark may have wished to demonstrate Jesus’ solidarity with creation’s suffering and Jesus’ sympathy with the Holy Spirit.[58]

L23-24 ὁ δὲ ἀποκριθεὶς εἶπεν αὐτοῖς (Matt. 12:39; 16:2). The wording of the two Matthean versions of Sign-Seeking Generation is identical in L23-24. This point marks the beginning of the cross-pollination which characterizes much of the rest of the two Matthean versions of Sign-Seeking Generation.

On the author of Matthew’s redactional use of ἀποκρίνειν…λέγειν/εἰπεῖν constructions, see above, Comment to L8-9.[59]

L24 λέγειν] (GR). As we noted above, in Comment to L13, ἄρχειν + infinitive constructions are not typical of Lukan redaction, so Luke’s λέγειν in L24 may be a reflection of Anth. The enclosing brackets indicate a degree of uncertainty regarding this portion of the reconstruction.

[לוֹמַר (HR). On On reconstructing ἄρχειν + λέγειν—ἄρχειν (archein, “to begin”) appears in L13—with הִתְחִיל לוֹמַר (hitḥil lōmar, “he began to say”), see above, Comment to L13.

λέγει (Mark 8:12). Mark’s historical present (“he says”) is un-Hebraic but typical of the author of Mark’s redactional style.[60]

L25 [omission] (Matt. 16:2b-3). Scholarly opinion is divided concerning whether the insertion of Interpreting the Time into the second of Matthew’s two versions of Sign-Seeking Generation is original or a scribal interpolation. Arguments against the originality of the insertion include its absence from authoritative manuscripts (such as Codex Vaticanus) and the presence of several lexical items not found elsewhere in the Gospel of Matthew.[61] Arguments for the originality of the insertion include its broad attestation and the difficulty of explaining the dramatic departure from scribal practice such an interpolation would entail.[62] A scribal interpolation would be more credible if it had been copied directly from Luke 12:54-56, but the extremely low levels of verbal identity between the Lukan and Matthean versions of Interpreting the Time[63] require us to assume either that the scribes who interpolated Interpreting the Time also extensively revised the Lukan version or that they interpolated Interpreting the Time from an otherwise unknown source,[64] neither of which seems likely. On the other hand, extensive revision of sayings is characteristic of the author of Matthew’s style (his treatment of Sign-Seeking Generation is a case in point!), as is the gathering together of disparate materials in order to form longer discourse units. Meanwhile, the unique vocabulary in Matt. 16:2b-3 can be accounted for by the unusual subject matter, and the omission of Interpreting the Time can be explained by its obvious intrusion into the Sign-Seeking Generation context (as any scribe could discern from the earlier version in Matt. 12:38-40, as well as the Markan and Lukan parallels). The inaccuracy of Matthew’s weather signs for regions other than that in which the Matthean community was located may have been another factor in the scribal omission of Matthew’s version of Interpreting the Time.[65]

If the insertion of Interpreting the Time can be attributed to the author of Matthew, then his reason for doing so may be two-fold. First, the insertion makes Matthew’s second version of Sign-Seeking Generation more than an abbreviated repetition of the first.[66] Second, the author of Matthew may have wished to counter the inference that Jesus was incapable of producing a sign. By inserting Interpreting the Time, the author of Matthew may have been communicating to his readers that producing a sign would have been useless because those who demanded a sign out of heaven were not even capable of interpreting natural atmospheric phenomena. Explaining away uncomfortable facts is an attested Matthean strategy.[67]

L26 τί ἡ γενεὰ αὕτη (Mark 8:12). Mark’s version of Sign-Seeking Generation is unique in having Jesus respond to the demand for a sign with a question. The Lukan-Matthean agreement against Mark’s interrogative is less strong than it might be because each author formulates Jesus’ opening statement differently. Nevertheless, the Lukan-Matthean agreement against Mark in L27 confirms that Luke preserves Anth.’s non-interrogative form of the saying.[68]

ἡ γενεὰ αὕτη (GR). It is only with the commencement of Jesus’ direct speech in L26 that the Synoptic Gospels begin to follow the wording of Anth. The phrase ἡ γενεὰ αὕτη (hē genea havtē, “this generation”) is one of the verbal links that binds Sign-Seeking Generation to the two previous pericopae in the reconstructed “Choose Repentance or Destruction” complex (Generations That Repented Long Ago, L10, L17; Innocent Blood, L17, L26).

By omitting ἡ γενεὰ αὕτη the author of Matthew was not only able to streamline Jesus’ saying,[69] he was also able to eliminate the temporal sense of γενεά (“generation”), leaving his readers to infer that the meaning of γενεά is “race.” Thus, the author of Matthew besmirched the entire Jewish people (regardless of time or place) instead of leveling a critique at certain dangerous trends in contemporary Jewish society, as Jesus’ saying originally intended.[70]

דּוֹר זֶה (HR). On reconstructing γενεά (genea, “generation”) with דּוֹר (dōr, “generation”), see Generations That Repented Long Ago, Comment to L10.

Since in Mishnaic Hebrew the demonstrative adjective and the noun it modifies rarely take the definite article,[71] and since we prefer to reconstruct direct speech in Mishnaic-style Hebrew, both דּוֹר and זֶה are anarthrous in HR.

L27-35 Beginning in L27 and continuing until L35 the wording of the two Matthean versions of Sign-Seeking Generation is identical, except for a variant reading of Codex Vaticanus in L29 and the addition of τοῦ προφήτου (tou profētou, “the prophet”) to Jonah’s name in L36. This agreement is to be explained by the Matthean method of cross-pollination by which the author of Matthew allowed doublets and parallel sayings to influence one another. It is clear from the Lukan-Matthean agreements in L27-35 that the author of Matthew preferred Anth.’s formulation of Jesus’ saying over Mark’s, though not without adding certain touches of his own.

L27 γενεὰ πονηρά ἐστιν (GR). Since the absence of ἐστιν (estin, “he/she/it is”) in Matt. 12:39 and Matt. 16:4 is of a piece with the author of Matthew’s omission of ἡ γενεὰ αὕτη (“this generation”) in L26 (on which, see Comment to L26), it is probable that Luke’s ἐστιν in L27 comes from Anth.

דּוֹר רָשָׁע הוּא (HR). On reconstructing γενεά (genea, “generation”) with דּוֹר (dōr, “generation”), see above, Comment to L26.

There are two main possibilities for reconstructing πονηρός (ponēros, “evil”):[72] רַע (ra‘, “evil”) and רָשָׁע (rāshā‘, “wicked”). The first option is well established by a plentitude of instances in which πονηρός occurs as the LXX translation of רַע,[73] and it has a parallel in Deut. 1:35, where הַדּוֹר הָרָע הַזֶּה (hadōr hārā‘ hazeh, “this evil generation”) refers to the generation that wandered with Moses forty years in the desert. The second option finds less support from LXX, although there are instances in which πονηρός occurs as the translation of רָשָׁע (2 Kgdms. 4:11; Isa. 53:9), but it has parallels in rabbinic literature, where the term דּוֹר רָשָׁע (dōr rāshā‘, “wicked generation”) is applied to the contemporaries of Noah:

כל אדם כשר שעומד בתוך דור רשע זכה ליטול שכר כולו נח עמד בדור המבול זכה ליטול שכר כולו

Every upright person who stands out in a wicked generation [דּוֹר רָשָׁע] deserves to take the wage of the whole generation. Noah, who stood out in the generation of the flood, deserved to take the wage of the whole generation…. (Sifre Num. Zuta 27:1 [ed. Horovitz, 316])

כעבור סופה ואין רשע וצדיק יסוד עולם. כעבור סופה ואין רשע זה דור המבול, וצדיק יסוד עולם זה נח

As a whirlwind passes and is no more, [so with] a wicked [רָשָׁע] [one], but a righteous [one is] established forever [Prov. 10:25]. As a whirlwind passes and is no more, [so] a wicked [רָשָׁע] [one]: this is the generation of the flood [דּוֹר הַמַּבּוּל]. But a righteous [one is] established forever: this is Noah. (Gen. Rab. 30:1 [ed. Theodor-Albeck, 1:270])

We find reconstructing γενεὰ πονηρά (“evil generation”) as דּוֹר רָשָׁע (“wicked generation”),[74] with its possible allusion to Noah’s generation, to be attractive, for as we noted in Generations That Repented Long Ago, Comment to L10, the phrase “this generation” (cf. L26) occurs only once in Scripture, when God describes Noah as צַדִּיק לְפָנַי בַּדּוֹר הַזֶּה (tzadiq lefānai badōr hazeh, “righteous before me in this generation”; Gen. 7:1).

Noah and the Ark illustrated by Pauline Baynes

That Jesus would compare his sign-seeking generation to the generation of the flood is made more plausible when we recollect that elsewhere Jesus compared the sudden catastrophe that engulfed the people of Noah’s generation to the cataclysmic events that would take place “in the days of the Son of Man” (Luke 17:26-27; cf. Matt. 24:37-39). Indeed, it is likely that it was 1) the reorganizing work of the Anthologizer, who clumped Son of Man sayings together after separating them from their original contexts, and 2) slight editorial changes introduced by the synoptic evangelists that make it seem like Days of the Son of Man describes the eschatological judgment. Originally, Days of the Son of Man may have been about the destruction Jesus warned was about to come upon his generation. For this reason we have placed Days of the Son of Man after Sign-Seeking Generation in the reconstructed “Choose Repentance or Destruction” complex. Given our suspicion that Jesus intended to compare his contemporaries to Noah’s generation, we think דּוֹר רָשָׁע is preferable for HR, since reconstructing γενεὰ πονηρά as דּוֹר רָע would more naturally lead to a comparison with the generation that wandered with Moses in the desert.

L28 καὶ μοιχαλὶς (Matt. 12:39) ∥ καὶ μοιχαλεὶς (Matt. 16:4). Some scholars have argued that the description “and adulterous,” which Matthew’s two versions of Sign-Seeking Generation add to “evil generation,” is original and that the author of Luke dropped καὶ μοιχαλίς (kai moichalis, “and adulterous”) because he feared his Gentile readers would not understand that “adulterous” is Jewish parlance for “unfaithful to God.”[75] But even if Gentile readers were incapable of appreciating the Jewish connotation of “adulterous,”[76] they certainly would have understood its pejorative sense, since in the ancient world abhorrence of adultery (defined as sexual intercourse with another man’s wife) was not unique to Judaism. Thus, the suggestion that the author of Luke dropped “and adulterous” from Sign-Seeking Generation lacks conviction.

It is more likely that καὶ μοιχαλίς in L28 is a product of the author of Matthew’s denigration of the Jewish people. The author of Matthew would have encountered the phrase “adulterous generation” in Mark 8:38, and his recollection of this memorable phrase probably accounts for its presence in the two Matthean versions of Sign-Seeking Generation.[77]

L29 σημεῖον ζητεῖ (GR). Text critics regard σημεῖον ἐπιζητεῖ (sēmeion epizētei, “demands a sign”), rather than Vaticanus’ σημεῖον αἰτεῖ (sēmeion aitei, “asks for a sign”), as the original reading in Matt. 16:4. We concur with this judgment, since in both his versions of Sign-Seeking Generation the author of Matthew appears to have intentionally worded Jesus’ refusal to give a sign identically. We have therefore to choose between Matthew’s ἐπιζητεῖν (epizētein, “to demand”) and Luke’s and Mark’s ζητεῖν (zētein, “to seek”) for GR. Since Matthew’s emphatic ἐπιζητεῖν gives Jesus’ saying an even more negative coloring than the versions in Luke and Mark by implying that sign-seeking was itself a culpable action (i.e., the demand was impudent), it is likely that ζητεῖν in Luke and Mark reflects the wording of Anth.[78]

סִימָן הוּא מְבַקֵּשׁ (HR). For reconstructing σημεῖον (sēmeion, “sign”) we have two main options. The first option is אוֹת (’ōt, “sign”), which the LXX translators usually rendered as σημεῖον.[79] Likewise, most instance of σημεῖον in LXX occur as the translation of אוֹת.[80] The second option is סִימָן (simān, “sign,” “omen”), a post-biblical Hebrew term derived from σημεῖον.[81] The following are examples of סִימָן that occur in tannaic sources:

הַמִּתְפַּלֵּל וְטָעָה סִימַן רַע לוֹ וְאִם שְׁלִיח צִיבּוּר הוּא סִימַן רַע לְשׁוֹלְחָיו

The one who prays and makes a mistake, it is a bad sign [סִימַן רַע] for him. And if he is a public representative, it is a bad sign [סִימַן רַע] for his constituents. (m. Ber. 5:5)

בזמן שהמאורות לוקין סימן רע לאומות העולם…ר′ מאיר או′ בזמן שהמאורות לוקין סימן רע לשונאיהן של ישראל מפני שהן למודי מכות…בזמן שחמה לוקה סימן רע לאומות העולם לבנה לוקה סימן רע לשונאיהם של ישראל מפני שהגוים מונין לחמה וישראל מונין ללבנה בזמן שלוקה במזרח סימן רע ליושבי מזרח במערב סימן רע ליושבי מערב באמצע סימן רע לעולם

When the heavenly bodies are eclipsed it is a bad sign [סִימָן רַע] for the peoples of the world…. Rabbi Meir says, “When the heavenly bodies are eclipsed it is a bad sign [סִימָן רַע] for the enemies of Israel [i.e., for Israel itself—DNB and JNT], for they are accustomed to beatings….” When the sun is eclipsed it is a bad sign [סִימָן רַע] for the peoples of the world, when the moon is eclipsed it is a bad sign [סִימָן רַע] for the enemies of Israel [i.e., for Israel itself—DNB and JNT], because the Gentiles calculate the date by the sun, but Israel calculates the date by the moon. When the sun is eclipsed in the east it is a bad sign [סִימָן רַע] for the inhabitants of the east, when it is eclipsed in the west it is a bad sign [סִימָן רַע] for the inhabitants of the west, when it is eclipsed at the zenith it is a bad sign [סִימָן רַע] for the world. (t. Suk. 2:6; Vienna MS)

עצרת פעמים שחל להיות בחמשה ובששה ובשבעה לא פחות ולא יותר ר′ יהודה אומר חל להיות בחמשה סימן רע לעולם בששה סימן בינוני בשבעה סימן יפה לעולם אבא שאול אומר כל זמן שיום טוב של עצרת ברור סימן יפה לעולם

Atzeret [i.e., Shavuot—DNB and JNT] sometimes happens to be on the fifth, sometimes on the sixth, and sometimes on the seventh of the month [of Sivan—DNB and JNT], neither less nor more. Rabbi Yehudah says, “If it is on the fifth, it is a bad sign [סִימָן רַע] for the world, on the sixth it is an ambivalent sign [סִימָן בֵּינוֹנִי], on the seventh a good sign [סִימָן יָפֶה] for the world.” Abba Shaul says, “As long as the holiday of Atzeret is clear it is a good sign [סִימָן יָפֶה] for the world.” (t. Arach. 1:9 [ed. Zuckermandel, 543])

Since we prefer to reconstruct direct speech in a Mishnaic style of Hebrew, we have adopted סִימָן for HR.

On reconstructing ζητεῖν (zētein, “to seek”) with בִּקֵּשׁ (biqēsh, “seek,” “request”), see Hidden Treasure and Priceless Pearl, Comment to L12. Several instances of בִּקֵּשׁ סִימָן (biqēsh simān, “seek/request a sign”) occur in the following rabbinic source:

וְרַ′ יְהוּדָה בְּרַ′ שָׁלוֹם אָמַר: כַּהֹגֶן הוּא מְדַבֵּר תְּנוּ לָכֶם מוֹפֵת, וְכֵן אַתָּה מוֹצֵא בְנֹחַ אַחַר כָּל הַנִּסִים שֶׁעָשָׂה לוֹ הַקָּדוֹשׁ בָּרוךְ הוּא בַּתֵּבָה וְהוֹצִיאוֹ מִמֶּנָּה אָמַר לוֹ: וְלֹא יִהְיֶה עוֹד מַבּוּל לְשַׁחֵת הָאָרֶץ, הִתְחִיל מְבַקֵּשׁ סִמָּן עַד שֶׁאָמַר לוֹ הַקָּדוֹשׁ בָּרוּךְ הוּא אֶת קַשְׁתִּי נָתַתִּי בֶּעָנַן וְהָיְתָה לְאוֹת בְּרִית בֵּינִי וּבֵין הָאָרֶץ, וּמָה נֹחַ הַצַּדִּיק הָיָה מְבַקֵּשׁ סִמָּן, פַּרְעֹה הָרָשָׁע עַל אַחַת כַּמָּה וְכַמָּה. וְכֵן אַתַּה מוֹצֵא בְחִזְקִיָּה בְּשָׁעָה שֶׁבָּא יְשַׁעְיָה וְאָמַר לוֹ כֹּה אָמַר ה′ וְגוֹ′ הִנְנִי רֹפֵא לָךְ בַּיּוֹם הַשְּׁלִישִׁי תַּעֲלֶה בֵּית ה″, הִתְחִיל לְבַקֵּשׁ סִמָּן, שֶׁנֶּאֱמַר וַיֹּאמֶר חִזְקִיָּהוּ אֶל יְשַׁעְיָהוּ מָה אוֹת כִּי יִרְפָּא ה′ לִי וְעָלִיתִי בַּיּוֹם הַשְּׁלִישִׁי בֵּית ה″, וּמָה חִזְקִיָּהוּ הַצַּדִּיק בִּקֵּשׁ אוֹת, פַּרְעֹה הָרָשָׁע לֹא כָל שֶׁכֵּן…וּמָה אִם הֵצַּדִּיקִים מְבַקְּשִׁים סִמָּן, הָרְשָׁעִים, עַל אַחַת כַּמָּה וְכַמָּה

And Rabbi Yehudah said in the name of Rabbi Shalom, “It was natural when he [i.e., Pharaoh—DNB and JNT] said, Give a sign [Exod. 7:9], for so you find with Noah. After all the miracles that the Holy One, blessed be he, did for him in the ark he brought him out and he said to him, And a flood will never again wipe out the earth [Gen. 9:11], whereupon he [i.e., Noah—DNB and JNT] began asking for a sign [מְבַקֵּשׁ סִמָּן] until the Holy One, blessed be he, said, My rainbow I have put in the clouds, and it will be a sign of the covenant between me and the earth [Gen. 9:13]. Now if Noah, who was righteous, would ask for a sign [הָיָה מְבַקֵּשׁ סִמָּן], how much more [would] Pharaoh, who was wicked [ask for a sign]? And so too you find with Hezekiah: when Isaiah came to him and said, Thus says the LORD…‘Behold! I am healing you. On the third day you will go up to the house of the LORD’ [2 Kgs. 20:5], he began to ask for a sign [לְבַקֵּשׁ סִמָּן], as it is said, And Hezekiah said to Isaiah, ‘What is the sign that the LORD will heal me and I will go up on the third day to the house of the LORD?’ [2 Kgs. 20:8]. Now if Hezekiah, who was righteous, asked for a sign [בִּקֵּשׁ אוֹת], how much more [would] Pharaoh, who was wicked [ask for a sign]? …So if the righteous ask for a sign [מְבַקְּשִׁים סִמָּן], the wicked will do so all the more.” (Exod. Rab. 9:1 [ed. Merkin, 5:122-123])[82]

On the other hand, בִּקֵּשׁ אוֹת (biqēsh ’ōt, “seek a sign”) also occurs in rabbinic sources:

שאלו תלמידיו את רבי יוסי בן קיסמא אימתי בן דוד בא אמר מתיירא אני שמא תבקשו ממני אות אמרו לו אין אנו מבקשין ממך אות א″ל לכשיפול השער הזה ויבנה ויפול ויבנה ויפול ואין מספיקין לבנותו עד שבן דוד בא אמרו לו רבינו תן לנו אות אמר להם ולא כך אמרתם לי שאין אתם מבקשין ממני אות אמרו לו ואף על פי כן אמר להם אם כך יהפכו מי מערת פמייס לדם ונהפכו לדם

His disciples asked Rabbi Yose ben Kisma, “When will the son of David come?” He said, “I am afraid lest you should ask of me a sign [תְּבַקְּשׁוּ מִמֶּנִּי אוֹת].” They said to him, “We are not asking of you a sign [מְבַקְּשִׁין מִמְּךָ אוֹת].” He said to them, “When this gate will have fallen and been rebuilt and fallen [a second time] and rebuilt and fallen [a third time] and they have not yet finished rebuilding, then the son of David will have come.” They said to him, “Our Rabbi, give us a sign [אוֹת]!”[83] He said to them, “And did you not say to me that you were not seeking a sign from me [מְבַקְּשִׁין מִמֶּנִּי אוֹת]?” They said to him, “Nevertheless.” He said to them, “If it is so, let the waters of the cave of Paneas turn to blood.” And they were turned to blood. (b. Sanh. 98a)[84]

As we discussed in the Conjectured Stages of Transmission section above, it is likely that the original meaning of Jesus’ statement that “this generation seeks a sign” was not that his contemporaries demanded proof from Jesus of his messianic status, but that his generation was desperately searching for signs that Israel was about to be divinely liberated from its subjection to the Roman Empire. By stating that no sign would be given to his generation, Jesus indicated that his generation had missed its opportunity to witness the redemption of Israel. The majority of his contemporaries had rejected the Kingdom of Heaven, and therefore the entire generation would be swallowed up in the destruction that would result from the inevitable collision with the legions of Rome.

L30 ἀμὴν λέγω (Mark 8:12). Although Codex Vaticanus omits ὑμῖν (hūmin, “to you”) in L30 following ἀμὴν λέγω (amēn legō, “Amēn I say”), text critics are surely correct in regarding this omission as a scribal error. Every other instance of ἀμήν in Mark is followed by λέγω ὑμῖν/σοι. In Mark “Amen I say to you” is a stereotyped phrase indicative of Markan redaction.[85]

The Lukan-Matthean agreement to omit ἀμὴν λέγω ὑμῖν (amēn legō hūmin, “Amēn! I say to you”) and Mark’s un-Hebraic use of ἀμήν as an adverb meaning “truly”[86] are strong indications that these words did not occur in Anth.’s version of Sign-Seeking Generation.

L31 καὶ σημεῖον (GR). In contrast to Mark’s un-Hebraic use of ἀμήν in L30, the authors of Luke and Matthew agreed upon the Hebraic use of καί (kai, “and”) to mean “but.” Their agreement against Mark is a clear indication that they reflect the wording of Anth.

וְסִימָן (HR). On reconstructing σημεῖον with סִימָן, see above, Comment to L29.

L32 εἰ δοθήσεται (Mark 8:12). Many scholars regard Mark’s εἰ δοθήσεται (ei dothēsetai, “if it will be given”) as a blatant Hebraism, the εἰ (“if”) being equivalent to אִם (’im, “if”) in an expression of emphatic negation.[87] For this reason some scholars have drawn the further conclusion that Mark’s version of Sign-Seeking Generation must be original. Nevertheless, there are reasons to doubt whether Mark’s εἰ δοθήσεται really is a Hebraism.[88] The Hebraic use of εἰ (ei, “if”) to express negation implies a self-imprecation, e.g., “[May the LORD do so-and-so to me] if [אִם] I do such and such.”[89] However, there is not a single example in all of Hebrew literature where אָמֵן (’āmēn, “Amen!”) introduces an unarticulated imprecation.[90] Moreover, Mark 8:12 is the only supposed instance of εἰ to express negation in the Gospel of Mark and, indeed, in the entire synoptic tradition.

Rather than regarding Mark’s εἰ as representing a suppressed oath, we believe it is preferable to regard Mark’s εἰ as interrogative (i.e., “Should [εἰ] a sign be given to this generation?”). This interpretation has three main advantages:

- Rapid-succession questions from a speaker delivered before the interlocutor(s) can respond are a typical feature of Markan style.

In summary, Jesus’ words in Mark 8:12 are best paraphrased as “Why does this generation seek for a sign? Honestly, I ask you, should this generation be given a [or possibly: another] sign?”

οὐ δοθήσεται (GR). Since it is doubtful that Mark’s εἰ δοθήσεται preserves a Hebraic negation, and since the Lukan-Matthean agreement against Mark to write οὐ δοθήσεται (ou dothēsetai, “will not be given”) in L32 undoubtedly reflects the wording of Anth., their shared non-Markan source, we have accepted οὐ δοθήσεται for GR.

לֹא יִנָּתֵן (HR). On reconstructing διδόναι (didonai, “to give”) with נָתַן (nātan, “give”), see Widow’s Son in Nain, Comment to L18. In LXX οὐ δοθήσεται (“will not be given”) occurs as the translation of לֹא יִנָּתֵן (lo’ yinātēn, “will not be given”) in the following example:

וְעַתָּה לְכוּ עִבְדוּ וְתֶבֶן לֹא יִנָּתֵן לָכֶם

And now, go! Slave away! But straw will not be given [לֹא יִנָּתֵן] to you. (Exod. 5:18)

νῦν οὖν πορευθέντες ἐργάζεσθε· τὸ γὰρ ἄχυρον οὐ δοθήσεται ὑμῖν

Now, therefore, go get working! For straw will not be given [οὐ δοθήσεται] to you. (Exod. 5:18)[91]

This verse is similar to our reconstruction in L31-33 not only in terms of vocabulary (viz., οὐ δοθήσεται/לֹא יִנָּתֵן), it also resembles our reconstruction in terms of word order (Greek: object→οὐ δοθήσεται→pronoun; Hebrew: -וְ + object → לֹא יִנָּתֵן → -לְ + pronominal suffix).

L33 αὐτῇ (GR). Once again the Lukan-Matthean agreement against Mark’s wording in L33 reveals the text of Anth.

L34-35 σημεῖον (Mark 8:12). His transformation of “No sign will be given…” into “Should a sign be given…?” forced the author of Mark to drop the exception clause found in the Lukan and Matthean versions of the saying (i.e., “except the sign of Jonah”). Dropping the reference to Jonah was convenient for the author of Mark, who, by omitting Generations That Repented Long Ago, chose not to develop the Jonah theme in his Gospel.

εἰ μὴ τὸ σημεῖον Ἰωνᾶ (GR). The Lukan-Matthean agreement against Mark to write “except the sign of Jonah” ensures that this exception clause did appear in Anth. (hence its inclusion in GR).[92] Nevertheless, there are serious reasons for doubting that these words reflect the underlying Hebrew Ur-text. In other words, it may be that the Anthologizer added the words εἰ μὴ τὸ σημεῖον Ἰωνᾶ (ei mē to sēmeion Iōna, “except the sign of Jonah”) as an explanatory gloss, probably introduced in order to remove the apparent contradiction within Jesus’ statement that no sign would be given but that the Son of Man would be a sign to this generation.

What are the reasons for regarding εἰ μὴ τὸ σημεῖον Ἰωνᾶ as a secondary addition to Sign-Seeking Generation? First, no other ancient Jewish source attests the existence of a “sign of Jonah.”[93] Second, whether “the sign of Jonah” should be understood as “the sign that is Jonah” (i.e., Jonah is himself the sign)[94] or “the sign Jonah gave,” it is hard to see how a prophet from the distant past could be a sign for (or have given a sign to) “this generation,” namely Jesus’ contemporaries. Third, the words “except the sign of Jonah” contradict Jesus’ statement in Luke 11:30 that “the Son of Man will be a sign to this generation” (i.e., the Son of Man, not the sign of Jonah, will be the sign given to Jesus’ generation).[95]

If the words “except the sign of Jonah” are a secondary addition, why was their insertion deemed to be desirable, and how did the insertion come about? The most likely scenario is as follows: in the Hebrew Life of Yeshua Jesus said something like, “This generation seeks a sign [i.e., of deliverance], but no sign will be given to it. As Jonah was a sign [of doom] to the Ninevites, so will the Son of Man be a sign [of doom] to this generation.” It may be that in the original Hebrew saying Jesus used two different terms for “sign” in this pericope: סִימָן (simān) in the first sentence, אוֹת (’ōt) in the second.[96] Or, Jesus may have used אוֹת in both parts of the saying. Either way, in Hebrew it would have been clear to listeners that Jesus meant two different things when he spoke of signs. In the first sentence “sign” was clearly used in a positive sense. Jesus’ generation was looking for a good omen, a sign of hope, a divine manifestation. In the second sentence “sign” would have conveyed a distinctly negative sense. As Hebrew speakers steeped in the scriptural tradition would have known, prophets and holy men who became “signs” bore witness against their generations and signaled their doom.[97] Thus, in Hebrew, Jesus’ meaning would have been understood in the following manner: You are looking for one kind of sign (i.e., a sign of deliverance) and you won’t get it. But you will get another kind of sign you’re not looking for (i.e., a sign of doom).

When Jesus’ saying was translated into Greek, the contrasting meanings of “sign” were flattened as “sign” was translated in both sentences with the same term, σημεῖον (sēmeion).[98] As a result, in Greek, Jesus’ saying sounded contradictory: No sign will be given. The Son of Man will be a sign. Either the Greek translator did not notice the apparent contradiction in his translation, or he believed that his readers would understand the Hebrew nuances behind his translation, or he assumed that the original meaning of Jesus’ saying would be explained when his translation was read in a communal setting. In any case, the Greek translator of the Hebrew Life of Yeshua let the contradiction stand in the text he produced.

When the Anthologizer read the Greek translation of Sign-Seeking Generation he sensed the contradiction and attempted to alleviate it by inserting the exception clause between the two statements. “Except the sign of the Son of Man” would have been more apt as an emendation, but Jonah is mentioned first in Jesus’ saying, which probably accounts for the Anthologizer’s word choice: No sign will be given to it except the sign of Jonah. Just as Jonah was a sign to the Ninevites, so the Son of Man will be a sign to this generation.

We believe that regarding “except the sign of Jonah” as an editorial addition to Jesus’ saying is a better solution than the alternative, which is to accept “except the sign of Jonah” as original and either ignore the contradictions the inclusion of these words creates or attempt to explain them away. Scholars who regard “except the sign of Jonah” as original have to scramble to explain what “the sign of Jonah” could possibly be. Some scholars believe that Jonah’s deliverance from the belly of the great fish was the sign of Jonah, but this explanation relies too heavily on the Matthean version of Jonah, which is highly suspect. Identifying the sign of Jonah as Jonah’s deliverance from the great fish cannot explain how Luke’s version of Sign-Seeking Generation, which makes no reference to the great fish, came into being.[99] Other scholars maintain that “the sign of Jonah” should not be taken at face value to refer to the biblical prophet. Either Ἰωνᾶς (Iōnas, “Jonah”) is a mistaken translation of יוֹנָה (yōnāh, “dove”), and “the sign of the dove” refers to Jesus’ baptism,[100] or, instead of Jonah, John the Baptist was originally intended as the sign that would be given to “this generation.”[101] Of course, accepting either of these two explanations requires us to assume that both Luke 11:30 and Matt. 12:40 are later elaborations of the Sign-Seeking Generation saying that were developed after the original identity of the sign was forgotten.[102] Our solution is less drastic than any of these alternatives. It removes the contradictions inherent in Luke’s version of Sign-Seeking Generation, it avoids having to invent contrived explanations of what the sign of Jonah might be, and it explains why and how the explanatory gloss was inserted into Jesus’ saying.[103]

[אֶלָּא] (HR). Since we consider the words “except the sign of Jonah” to be an explanatory gloss added by the Anthologizer, we have not provided a reconstruction of εἰ μὴ τὸ σημεῖον Ἰωνᾶ in HR. It is just possible, however, that the Anthologizer wrote εἰ μὴ τὸ σημεῖον Ἰωνᾶ in place of a transition marker such as ἀλλά (alla, “but”), which might have represented אֶלָּא (’elā’, “but,” “rather”) in the Hebrew Life of Yeshua.[104] On account of this possibility, we have placed אֶלָּא within brackets in L34.

L36 τοῦ προφήτου (Matt. 12:39). Although it is easy to revert Matthew’s τοῦ προφήτου (tou profētou, “the prophet”) to Hebrew, we suspect that this title was added to Jonah’s name by the author of Matthew.[105] The author of Luke would have had no particular reason to omit Jonah’s title had he seen it in Anth. Moreover, we have observed a tendency elsewhere in Matthew to add additional identifiers after an individual’s name—for example, Matthew “the toll collector” in Matt. 10:3 (see Choosing the Twelve, Comment to L35) and Abel “the righteous” and Zechariah “son of Berechiah” in Matt. 23:35 (see Innocent Blood, Comment to L18 and Comment to L20).

L37-46 Although the analogies drawn between Jonah and the Son of Man in Luke 11:30 and Matt. 12:40 are very different, their identical structures (καθὼς/ὥσπερ γὰρ…Ἰωνᾶς…οὕτως ἔσται…ὁ υἱὸς τοῦ ἀνθρώπου [“For just as…Jonah…so will be…the Son of Man”]) prove that a single tradition stands behind the two disparate versions.[106] Most scholars are agreed that the original tradition standing behind Luke 11:30 and Matt. 12:40 is better preserved in Luke than in Matthew,[107] since it is difficult to explain why the author of Luke would have rejected Matthew’s Christological interpretation with its allusion to Jesus’ death and resurrection had he known it, whereas it is easy to see how a source like Luke 11:30 could be adapted into an allegorical interpretation like Matt. 12:40. Moreover, the wording of Luke 11:30, which mentions “Ninevites” (L39) and “this generation” (L44), reveals how Generations That Repented Long Ago, which includes these key terms at L15 and L17, came to be attached to the end of Sign-Seeking Generation.[108] Had Sign-Seeking Generation originally referred to the three days and three nights of Jonah’s sojourn in the belly of the great fish instead of the Son of Man’s being a sign to “this generation” as Jonah had been a sign to the “Ninevites,” it would be more difficult to explain how these two pericopae came to be conjoined at the pre-synoptic stage of transmission.

L37 καθὼς γὰρ ἐγένετο (GR). Since the authors of Luke and Matthew never agree on the use of the adverb καθώς (kathōs, “just as”)[109] and only agree on the use of ὥσπερ (hōsper, “just as”) once (Matt. 24:27 ∥ Luke 17:24),[110] it is difficult to decide which to accept for GR. Ease of Hebrew retroversion is no help in reaching this decision, since both options revert to Hebrew with equal facility.[111] In our opinion, two points tip the balance slightly in favor of Luke’s καθώς.[112] The first point is simply the pervasive Matthean editorial activity throughout Matt. 12:40. The author of Matthew extensively paraphrased Anth.’s wording in L37-46, and therefore it is a priori more likely that he changed καθώς to ὥσπερ than that the author of Luke changed ὥσπερ to καθώς. The second point is that in Days of the Son of Man the author of Luke twice used the adverb καθώς (Luke 17:26, 28). This is significant because the author of Luke likely relied on Anth. as the source for this pericope, and what is more, prior to the Anthologizer’s reorganizing activity, Days of the Son of Man may have appeared immediately on the heels of Sign-Seeking Generation. In that case, it would be natural for καθώς to have been used in both pericopae.

With regard to our preference for Luke’s verb form ἐγένετο (egeneto, “it was”) over Matthew’s ἦν (ēn, “it was being”), it is evident that beginning with ἦν and continuing to the end of the first half of the comparison (L38-41) the author of Matthew quoted directly from the book of Jonah (LXX):

καὶ προσέταξεν κύριος κήτει μεγάλῳ καταπιεῖν τὸν Ιωναν· καὶ ἦν Ιωνας ἐν τῇ κοιλίᾳ τοῦ κήτους τρεῖς ἡμέρας καὶ τρεῖς νύκτας

And the Lord commanded a great sea monster to swallow Jonah. And Jonah was in the belly of the sea monster three days and three nights. (Jonah 2:1)

Thus, Luke’s non-Septuagintal phrasing is more likely to represent the Greek translation of the words of Jesus.

כְּשֵׁם שֶׁהָיָה (HR). Whereas in Biblical Hebrew comparisons were usually constructed with formulae such as [no_word_wrap]כְּ-…כֵּן[/no_word_wrap] (ke-…kēn, “as…so”) or [no_word_wrap]כַּאֲשֶׁר…כֵּן[/no_word_wrap] (ka’asher…kēn, “as when…so”), in Mishnaic Hebrew comparisons were typically expressed with the formula [no_word_wrap]כְּשֵׁם שֶׁ-…כָּךְ[/no_word_wrap] (keshēm she-…kāch, “just as…so”).[113] Since we prefer to reconstruct direct speech in a Mishnaic style of Hebrew, we have adopted the latter formulation for HR.

L38 Ἰωνᾶς (GR). The definite article ὁ (ho, “the”) which precedes Ἰωνᾶς (Iōnas, “Jonah”) in Codex Vaticanus (Luke 11:30) is probably a scribal accretion added (perhaps unconsciously) as a stylistic improvement of Luke’s Greek. The absence of the definite article in the Matthean parallel is due to the author of Matthew’s conformity to the LXX wording of Jonah 2:1, but the absence of ὁ before Ἰωνᾶς in other textual witnesses to Luke 11:30 probably reflects the original Lukan text, which in turn reflects the wording of Anth.