This article originally appeared in the JP magazine as a sidebar attached to “John’s Targumic Allusions” by Randall Buth.

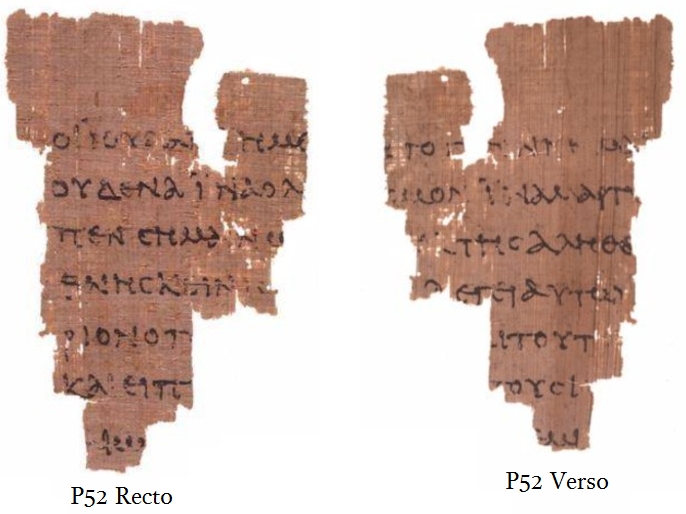

Last century many scholars viewed the Gospel of John as a second-century work of the Greek church, and it was taken as axiomatic that the writer knew and used the Synoptic Gospels. However, the discovery in Egypt of an early second-century papyrus fragment[1] containing the text of John 18:31-33 (recto), 37-38 (verso) undermined the late dating of the book. Since John’s Gospel was circulating in Egypt by the early second century, as evidenced by this papyrus copy, the original must have been written in the first century or very early second century A.D. Today, most scholars would date the writing of John between A.D. 65-110, with A.D. 80-90 a common conclusion.

In 1938 the British scholar Percival Gardner-Smith published a widely influential book, Saint John and the Synoptic Gospels (Cambridge University Press), which suggested that John was independent of the Synoptics. Many scholars now have taken a middle position that treats John as an independent work, recognizing that its author probably knew at least one of the Synoptic Gospels but may not have used these Gospels as sources.

Much discussion in the last century centered on the Greek background of John’s Gospel. The debate was fueled by discussions about the philosophical background of the “logos” doctrine so prominent in the opening verse. However, nagging questions persisted about the unique geographical and Jewish background of the Gospel.

In John, most of Jesus’ ministry occurs in Judea, and it is John alone among the four Gospels that provides the long discussion with a Samaritan woman. The discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls has reinforced a trend to view the traditions transmitted by John as authentic. Some of the abstract terminology that appears in John, such as “light” and “darkness,” turns out to be prominent in writings of the Dead Sea sect. In addition, like John, the Qumran sectarians are highly critical of the Jerusalem Temple authorities, something that used to be considered a reason for questioning the Jewish background of John.

With the rediscovery of Jewish roots to John’s Gospel, scholars pay more attention to layers of historical data within the Gospel. This does not mean, however, that scholars now read John as unedited history. There is still a problem of determining where Jesus’ words end. (For example, do his words end at John 3:13 where the Good News Bible marks the end of the quotation, or at John 3:21 where the New International Version concludes Jesus’ speech?) John may not have been concerned to distinguish his own words from those of Jesus. In addition, the problem of the order of events in John’s Gospel is as difficult as ever (for instance, a cleansing of the Temple at the beginning of Jesus’ ministry rather than at its end as in the Synoptic Gospels).

- [1] Designated Papyrus Rylands Greek 457 (Gregory-Aland 𝔓52). Acquired in Egypt in 1920, this fragment is the earliest known manuscript of any identifiable portion of the New Testament. It was published by C. H. Roberts (An Unpublished Fragment of the Fourth Gospel [Manchester, 1935]). Roberts dated this fragment to the end of the first century–beginning of the second century A.D. (Roberts, Unpublished Fragment, 13-16). ↩