Every year his parents went to Jerusalem for the Feast of Passover. When he was twelve years old, they went up for the feast, according to the custom of the feast. When they had fulfilled the days [of the feast], his parents started home, unaware that the boy Jesus had stayed behind in Jerusalem. (Luke 2:41-43)

Luke states that Joseph and Mary made a pilgrimage to Jerusalem every Passover. The requirement of pilgrimage to the Temple in Jerusalem is mentioned in the passages of Scripture that deal with three annual festivals. Exodus 23:17 states: “Three times a year all your males shall appear before the Sovereign, the LORD.” Exodus 34:23 repeats this command almost verbatim, and the book of Deuteronomy characteristically adds further details:

Three times a year—on the Feast of Unleavened Bread, on the Feast of Weeks, and on the Feast of Booths—all your males shall appear before the Lord your God in the place that he will choose. They shall not appear before the Lord empty-handed. (Deut. 16:16)

During the Second Temple period these verses were not understood to mean that one was obliged to make a pilgrimage to Jerusalem three times a year, but rather that pilgrimage was associated with these festivals. Pilgrimage was considered a commandment that “has no measure,” as stated in Mishnah, Peah 1:1: “The following are the things for which no definite quantity is prescribed…appearing [before the Lord]….”

Thus, the commandment to “go up” to Jerusalem might be observed once every few years or perhaps only once in a lifetime.

Once a Year

A number of rabbinic traditions refer to people who were rather strict in observing the commandment of pilgrimage.[1] One such tradition is found in Tanhuma, Tetsaveh 13, which reads:

There was a scribe who used to make pilgrimage every year. He was recognized by the residents of Jerusalem as being a great scholar. They said to him: “We will give you fifty gold pieces a year if you will take up residence in our city.”

The midrashic (homiletic) account of the pilgrimage of Elkanah, the father of Samuel, to the tabernacle in Shiloh also indicates that pilgrimage once a year was quite acceptable:

Elkanah used to take with him his wife, children, sisters and all his relatives, and make the pilgrimage [to the tabernacle in Shiloh]. They slept in the squares of the towns and villages through which they passed. Their coming aroused great excitement in each community and the inhabitants would ask, “Where are you going?”

They would answer, “To the house of the Lord in Shiloh from where Torah and commandments go forth. Why don’t you join us and we will go together?”

Immediately their eyes filled with tears. “We will go with you [next year],” they answered.

“Very well,” the pilgrims said to them.

By the next year five families [of that community] had joined them on the pilgrimage, a year later ten families, until finally everyone was making the pilgrimage. (Yalkut Shim’oni, Torah, remez 77)

This midrash, which reflects the practice of the first century, praises Elkanah even though he goes on pilgrimage only once a year. The account in Luke agrees with such Jewish traditions about righteous individuals or families who made pilgrimage once a year.

Purpose of Pilgrimage

Young Jesus took advantage of the pilgrimage to Jerusalem to question the learned teachers about interpretations of Scripture, as well as to express opinions of his own. This is also in keeping with the rabbinic motif that one of the most important purposes of pilgrimage is to study Torah:

Rabbi Eliezer says: “When one brings the sacrifices that one has vowed to the Temple, he enters the Chamber of Hewn Stone and sees sages and their disciples sitting and engaging in the study of Torah. The sight inspires him also to study Torah.”

Rabbi Ishmael says: “When one brings the second tithe to the Temple, he enters the Chamber of Hewn Stone and sees sages and their disciples sitting and engaging in the study of Torah. The sight inspires him also to study Torah.” (Midrash Tannaim to Deut. 14:23)

Both Rabbi Eliezer and Rabbi Ishmael lived while the Second Temple was still standing and their words reflect the reality of that period.

Jesus in Jerusalem

The study of Torah while on pilgrimage in Jerusalem likewise agrees with events in the life of Jesus as described in the gospels. Jesus went to Jerusalem for the Feast of Hanukkah and taught in Solomon’s Porch in the Temple compound (John 10:22-24). When Jesus went to Jerusalem for the Feast of Tabernacles, he also taught in the Temple (John 7:14). And, when he went to Jerusalem for the last time at Passover, he sat opposite one of the treasuries of the Temple and taught Torah (Mark 12:41; Luke 21:1; John 8:2).

When Jesus was finally arrested, he berated his captors for coming to arrest him at such a late hour when he had been sitting daily in the Temple courtyards teaching (Matt. 26:55; Mark 14:48-49; Luke 22:52-53; cf. John 18:20). Jesus apparently taught in the temple courtyards in a manner similar to that of Rabban Yohanan ben Zakkai who used to “sit and teach daily[2] in the shade of the sanctuary” (Babylonian Talmud, Pesahim 26a).

Length of Stay

In Luke 2:43 it is stated that Jesus’ parents returned home when they had “fulfilled the days.” This implies that they not only spent the first day of Passover in Jerusalem, but a number of days there.

When the Bible discusses the Passover sacrifice, it adds: “And in the morning you may start back on your journey home” (Deut. 16:7). In other words, the Passover pilgrim could return home any time after the first day of the seven-day festival (traveling was forbidden on the first day of the festival).

However, rabbinic tradition dating from as early as the Second Temple period interpreted “in the morning” in this verse as referring not to the first day of the festival, but to the whole seven-day festival: “Scripture treats all of them [the days of Passover] as one morning [i.e., as one day]” (Mishnah, Zevahim 11:7; Babylonian Talmud, Zevahim 97a).

Thus, in the time of Jesus’ parents the Passover pilgrim did not return home after the first day of the festival, but only after he had “fulfilled the days.” A family of pilgrims stayed in Jerusalem for the entire seven days of the Feast of Passover, and the entire eight days of the Feast of Tabernacles.[3]

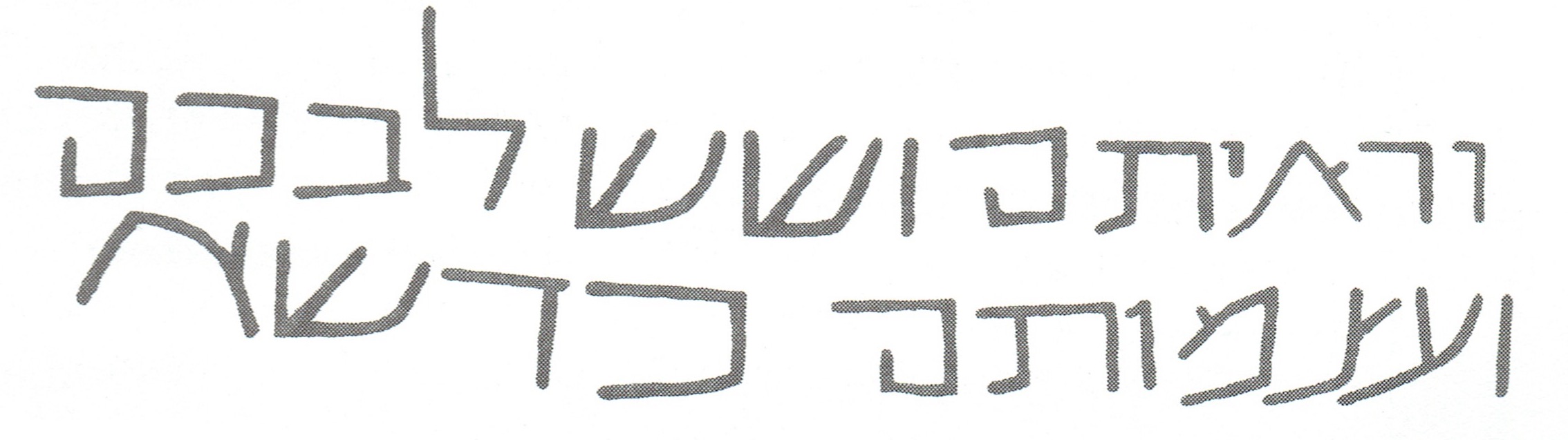

Sidebar by David Bivin: “Pilgrim’s Graffito”Revised: 8-Sep-2012In 1969, as excavators cleared centuries of debris away from the western wall of the Temple Mount, they made an unusual discovery. On the face of a monumental stone just above the level of the Byzantine street was a crude inscription in a Hebrew script typical of the Byzantine period: וראיתם ושש לבכם ועצמותם כדשא (“When you see this, your heart will rejoice and their limbs like grass”). The words of the inscription, with slight modifications, had been taken from a passage in Isaiah which reads: “For this is what the Lord says: ‘…As a mother comforts her child, so will I comfort you; you will find comfort in Jerusalem.’ When you see this, your heart will rejoice and your limbs [literally, “bones”] will flourish like grass” (Isa. 66:12-14).  A pilgrim inscribed a portion of a verse from Isaiah on one of the stones of the Western Wall of the Temple Mount. Photograph by Todd Bolen. Photo © BiblePlaces.com This inscription may have been a pilgrim’s expression of anticipation that the Temple would soon be rebuilt. In 362 A.D., the Roman emperor Julian gave permission to rebuild the Temple in Jerusalem, a decision which evoked immense enthusiasm among the Jewish people. Work did begin on the Temple, but an earthquake interrupted it. In 363 A.D., while the work was suspended, Julian died and rebuilding was never resumed. It may have been during the few months of euphoria at the prospect of the Temple being rebuilt that a Jewish pilgrim was inspired to inscribe this graffito on one of the stones near where the Temple had stood. Rabbinic literature shows that during the Byzantine period this passage from Isaiah frequently was interpreted messianically and was the basis for many sermons. Thus, it could have been used by a pilgrim to express his anticipation that the messianic age was dawning. |

Read more articles by Shmuel Safrai:

- Zechariah’s Prestigious Task

- With All Due Respect…

- Were Women Segregated in the Ancient Synagogue?

- Trees of Life

- The Value of Rabbinic Literature as an Historical Source

- The Synagogue the Centurion Built

And check out these recent JP articles:

- Character Profile: BeelzebulGet acquainted with this mysterious and sinister figure.

- What’s Wrong with Contagious Purity? Debunking the Myth that Jesus Never Became Ritually ImpureThe view that Jesus could not be affected by impurity and that Jesus was able to spread his purity to others is based on faulty assumptions and invalid inferences.

- Two Neglected Aspects of the Centurion’s Slave PericopeRitual impurity and the tensions resulting from Roman imperialism are two aspects of the Centurion’s Slave pericope that often go overlooked.

- “They Know Not What They Do”: The History of a Dominical SayingHow Luke 23:34 became embroiled in the Church’s conflicted relationship with its Jewish Roots.

- Why Do You Call Me ‘Lord’?: On the Origins of Jesus’ Dominical TitleThe confession “Jesus is Lord” is the simplest and earliest Christian creed. But how did referring to Jesus as “Lord” begin?

- Evidence of Pro-Roman Leanings in the Gospel of MatthewHindsight and political expedience shaped the author of Matthew’s view of the Roman Empire.

- [1] But who nevertheless made pilgrimage to Jerusalem only once a year and not three times as mentioned in the Bible. ↩

- [2] Here, the words כל היום (kol ha-yom, all day long) mean כל יום (kol yom, each day, daily). ↩

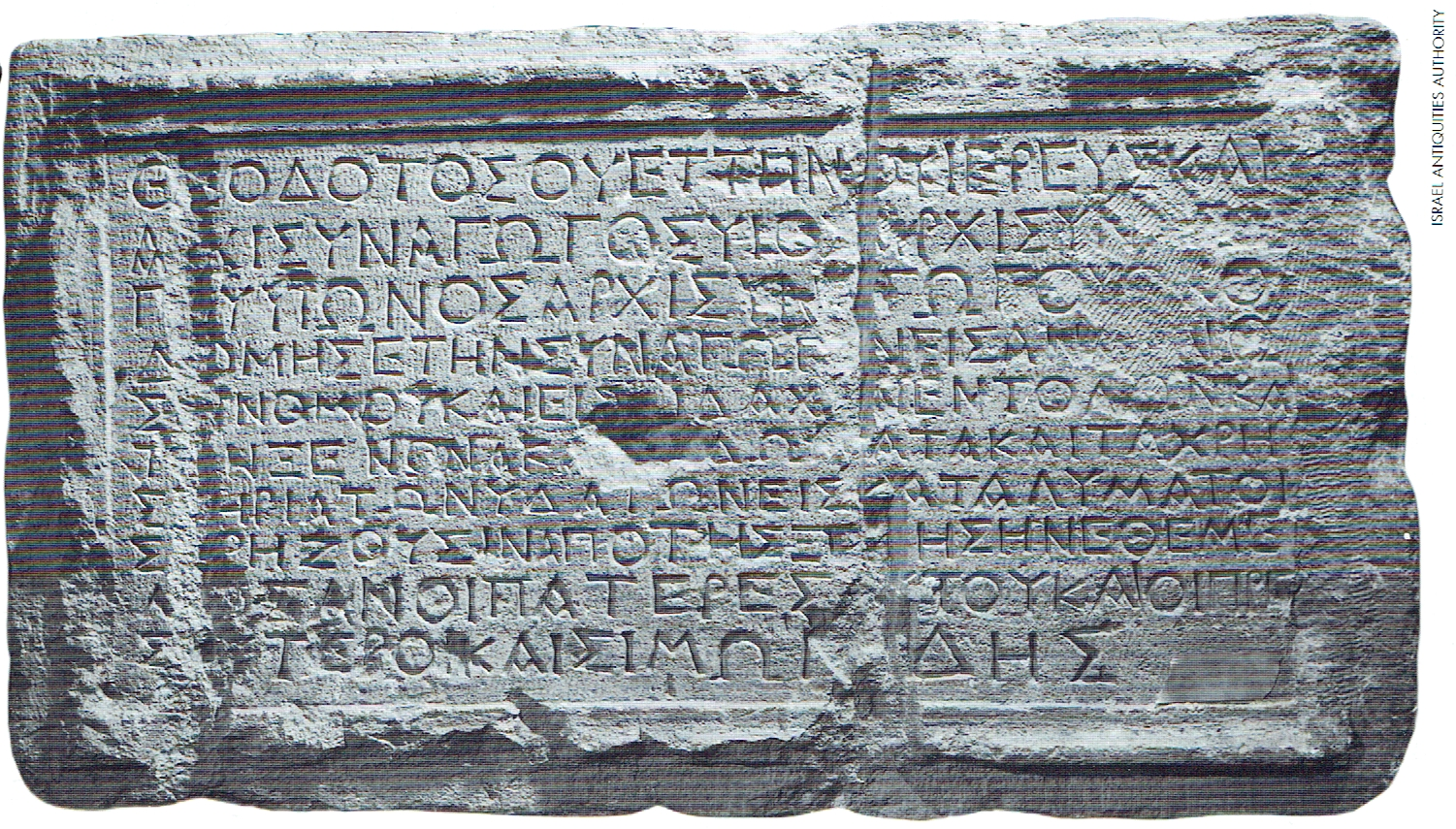

- [3] For more on pilgrimage in the first century, see “Synagogue Guest House for First-century Pilgrims.” ↩

![Shmuel Safrai [1919-2003]](https://www.jerusalemperspective.com/wp-content/uploads/userphoto/20.jpg)