The word “synoptic” is derived from συνόψεσθαι (sūnopsesthai), a Greek word meaning “to view together.” The Gospels of Matthew, Mark and Luke are known as the Synoptic Gospels because they present a similar view of the same series of events—the deeds and sayings of Jesus of Nazareth.

The Synoptic Gospels date from the first century A.D. and were composed in Greek, although the syntax and vocabulary of the texts suggest that some of the material originally existed in written form in either Hebrew or Aramaic. To date, scholars have collated more than 1,000 Greek manuscripts containing portions of one or more of the Synoptic Gospels.

None of the Synoptic Gospels gives the name of its author. The attribution of authorship to Matthew, Mark and Luke is a Christian tradition dating to the late second century A.D. The first Gospel may have been ascribed to Matthew because of the tradition that the disciple Matthew wrote a gospel in Hebrew which was translated to Greek. For example, Papias, the bishop of Hierapolis in Asia Minor during the mid-second century A.D., wrote that “Matthew put down the words of the Lord in the Hebrew language, and others have translated them, each as best he could” (Eusebius, Ecclesiastical History III 39, 16).

The Problem

The “synoptic problem” concerns the order in which Matthew, Mark and Luke were written, and the literary sources they may have used.[1] Although the many similarities among the Synoptic Gospels suggest an interdependence, there are also differences.

According to Luke 4:22, after Jesus spoke in his hometown synagogue in Nazareth the people said, “Is not this Joseph’s son?” According to Mark 6:3, they said, “Is not this the carpenter, the son of Mary…?” However, Matthew 13:55 recounts, “Is not this the carpenter’s son? Is not his mother called Mary?”

Jesus’ foretelling of Peter’s denial appears in all three Synoptic Gospels (Matt. 26:34; Mark 14:30; Luke 22:34). In Matthew and Luke, Jesus says that Peter will deny him three times before the cock crows, whereas according to Mark, Jesus says that Peter will deny him three times before the cock crows twice.

In a saying that appears only in Matthew and Luke, Jesus says, “What man of you, if his son asks him for bread, will give him a stone? Or if he asks for a fish, will give him a snake?” (Matt. 7:9-10); “What father among you, if his son asks for a fish, will instead of a fish give him a snake; or if he asks for an egg, will give him a scorpion?” (Luke 11:11-12).

For the past 200 years, scholars have been trying to determine the significance of such similarities and differences. It appears that the writers of the Synoptic Gospels borrowed from each other, or shared common sources, or both. But it is not always clear who borrowed from whom and which variants are the most original.

Solutions to the Problem

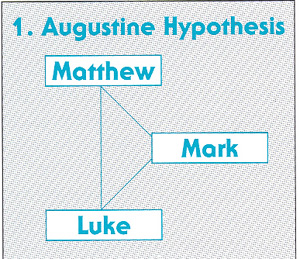

The earliest known theory of the synoptic relationship was proposed in De Consensu Evangelistarum I by Augustine, bishop of Hippo from 396-430 A.D. Augustine held that the Synoptic Gospels were written in the same order in which they appear in the New Testament, with Mark using Matthew’s account, and Luke referring to Matthew and Mark. This view held sway until about 1790, and has been revived by B. C. Butler.[2]

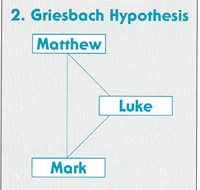

The oldest modern theory is that Matthew was the first Gospel written and was used by Luke, with Mark writing last and copying from both Matthew and Luke. This theory was first proposed in 1764 by Henry Owen, but has been called the Griesbach Hypothesis because it was advocated by Johann J. Griesbach in 1789. It was the dominant theory among scholars from about 1790 to 1870, and has been brought into currency again by William R. Farmer.[3]

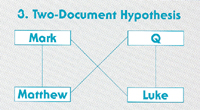

The most widely accepted synoptic theory today is the Two-Document Hypothesis which was proposed by Heinrich J. Holtzmann in 1863 and given its classic statement by Burnett Hillman Streeter in The Four Gospels: A Study of Origins (London: Macmillan, 1924). According to this theory, Mark wrote first and was used independently by Matthew and Luke. In addition to Mark, Matthew and Luke also worked from a non-canonical document consisting mostly of sayings of Jesus. This second source is a hypothetical text referred to by scholars as “Q,” thought to be an abbreviation of the German word Quelle, meaning “source.”

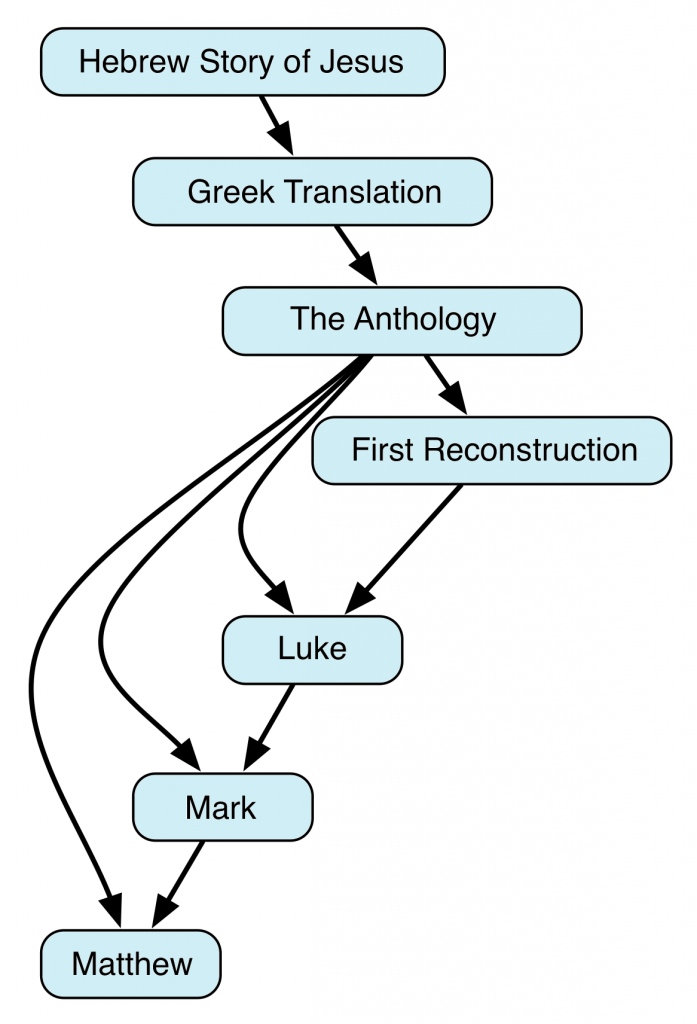

In 1922 William Lockton suggested a theory of Lukan priority. According to his hypothesis, Luke was written first, copied by Mark, who was in turn copied by Matthew who copied from Luke as well.[4] Forty years later Robert L. Lindsey independently reached a similar solution to the synoptic problem. He proposed a theory of Lukan priority that argues that Luke was written first and was used by Mark, who in turn was used by Matthew who did not know Luke’s Gospel.[5] This theory postulates two non-canonical documents that were unknown to the synoptists—a Hebrew biography of Jesus and a literal Greek translation of that original—and two other non-canonical sources known to one or more of the writers.

According to Lindsey, Matthew and Luke, and perhaps Mark as well, were acquainted with an anthology of Jesus’ words and deeds taken from the Greek translation of the Hebrew biography. Luke alone was acquainted with a second source, a Greek biography which attempted to reconstruct the story order of the original Hebrew text and its Greek translation. Mark used Luke while only rarely if at all referring to the anthology, while Matthew used Mark and the anthology. Luke and Matthew did not know each other’s Gospels, but independently used the anthology. As in the more popular Two-Document Hypothesis, Mark is the middle term between Matthew and Luke.

Importance of Hebrew

Lindsey arrived at his theory unintentionally. Attempting to replace an outdated Hebrew translation of the New Testament, he began by translating the Gospel of Mark, assuming it to be the earliest of the Synoptic Gospels. Although Mark’s text is relatively Semitic, it contains hundreds of non-Semitisms, such as the oft-repeated “and immediately,” which are not present in Lukan parallels. This suggested to Lindsey the possibility that Mark was copying Luke and not vice versa; with further research, this resulted in his solution to the synoptic problem.

A number of scholars in Israel, most prominently Hebrew University professor, the late David Flusser, espoused Lindsey’s source theory.[6] These scholars believe that a Hebrew vorlage lies behind the Greek texts of the Gospels. They maintain that by translating the Greek texts back into Hebrew and interpreting how this Hebrew text would have been understood by first-century readers, one gains a fuller understanding of the text’s original meaning.

In their emphasis on the importance of Hebrew, these Israeli scholars are following the pioneering work of Hebrew University professor M. H. Segal, who suggested as early as 1909 that mishnaic Hebrew showed the characteristics of a living language, and that the Jewish people in the land of Israel at the time of Jesus used Hebrew as their primary spoken and written language.[7]

Segal’s conclusions have been confirmed by the discovery of the Bar Kochva letters and other documents from the Dead Sea area. An important contribution to this subject is the two-part article by the late Hebrew University professor Shmuel Safrai, “Spoken Languages in the Time of Jesus,” Jerusalem Perspective 4.1 (1991): 3-8, 13, and “Literary Languages in the Time of Jesus,” Jerusalem Perspective 4.2 (1991): 3-8.

Lindsey’s research not only emphasizes the priority of Luke and/or Matthew when using their shared source, it draws particular attention to the Hebraic nature of the Greek text of the Synoptic Gospels and to the importance of attempting to translate that text into Hebrew before evaluating it. The recognition of the importance of Hebrew in understanding the Gospels is a new contribution to grappling with the synoptic problem, and is a harbinger of much fruitful research for the future.

To Learn More About This New Approach to the Synoptic Gospels, Check Out These JP Articles:

Lindsey explains four key points that support his solution to the Synoptic Problem.

Lindsey discusses the literary techniques of the author of Mark.

For Studies That Adopt This Approach to the Synoptic Gospels, We Recommend These JP Articles:

Paid Content

Premium Members and Friends of JP must be logged in to access this content: Login

If you do not have a paid subscription, please consider registering as a Premium Member starting at $10/month (paid monthly) or only $5/month (paid annually): Register

One Time Purchase Rather Than Membership

Rather than purchasing a membership subscription, you may purchase access to this single page for $1.99 USD. To purchase access we strongly encourage users to first register for a free account with JP (Register), which will make the process of accessing your purchase much simpler. Once you have registered you may login and purchase access to this page at this link:

- [1] Recent introductions to the synoptic problem are E. P. Sanders and Margaret Davies, Studying the Synoptic Gospels (London: SCM Press and Philadelphia: Trinity Press International, 1989); Robert H. Stein, The Synoptic Problem: An Introduction (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Book House, 1987). See also the introduction to the synoptic problem in Brad H. Young, Jesus and His Jewish Parables: Rediscovering the Roots of Jesus’ Teaching (Mahwah, NJ: Paulist Press, 1989), 129-163. ↩

- [2] B. C. Butler, The Originality of St. Matthew: A Critique of the Two-Document Hypothesis (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1951). ↩

- [3] William R. Farmer, The Synoptic Problem: A Critical Analysis ( 2d ed.; Dillsboro, NC: Western North Carolina Press, 1976). ↩

- [4] William Lockton, “The Origin of the Gospels,” Church Quarterly Review 94 (1922): 216-239 [click here to read a reissue of this article on JP]. Lockton subsequently wrote three books to substantiate his theory, all published by Longmans, Green and Co. of London: The Resurrection and Other Gospel Narratives and The Narratives of the Virgin Birth (1924); The Three Traditions in the Gospels (1926); and Certain Alleged Gospel Sources: A Study of Q, Proto-Luke and M (1927). ↩

- [5] Robert L. Lindsey, “A Modified Two-Document Theory of the Synoptic Dependence and Interdependence,” Novum Testamentum 6 (1963): 239-263. ↩

- [6] David Flusser, “Jesus,” in Encyclopaedia Judaica (Jerusalem, 1971), 10:10. ↩

- [7] M. H. Segal, “Mishnaic Hebrew and Its Relation to Biblical Hebrew and to Aramaic,” in Jewish Quarterly Review Old Series 20 (1908-9): 647-737. See also Segal’s A Grammar of Mishnaic Hebrew (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1927). ↩