How to cite this article: Joseph Frankovic, “Remember Shiloh!” Jerusalem Perspective 46/47 (1994): 24-31 [https://www.jerusalemperspective.com/2714/].

A fascinating passage for gaining a glimpse at how Jesus manipulated biblical texts to communicate effectively to fellow Jews in the first century is the Cleansing of the Temple. The episode is recorded in all four of the gospels;[1] however, in Luke it is very concise. His description is characteristic of Hebrew prose—fast moving and terse.

Quotation from Isaiah

Approaching the outer court of the temple, Jesus turned aside to chide the vendors,[2] who were capitalizing on a surge in business as throngs of pilgrims entered Jerusalem for the approaching Passover.[3] He was speaking to people who knew from rote memory extensive segments of the sacred text. Moreover, some were peers, professionals like himself who were experts in the Scriptures. Therefore, one should anticipate a degree of sophistication in Jesus’ manner of speech.[4]

Excerpting a sentence from a marvelous passage in Isaiah, Jesus powerfully communicated what the temple was ideally meant to be. The passage reads as follows:

Also the foreigners who join themselves to the LORD, to minister to Him, and to love the name of the LORD, to be His servants, every one who keeps from profaning the Sabbath, and holds fast My covenant; even those I will bring to My holy mountain, and make them joyful in My house of prayer. Their burnt offerings and their sacrifices will be acceptable on My altar; for My house will be called a house of prayer for all the peoples.[5]

When Jesus said three words בֵּיתִי בֵּית תְּפִלָּה (bē·TI bēt te·fi·LĀH, my house is a house of prayer), from Isaiah 56:7, many in the audience, particularly scribes and priests, recalled their context, which has been quoted above. The people were poignantly reminded of the noble purpose that God had envisioned for his temple.

Quotation from Jeremiah

Immediately after quoting Isaiah, Jesus said, “But you have made [my house] a den of robbers!” The phrase “den of robbers,” מְעָרַת פָּרִצִים (me·‘ā·RAT pā·ri·TZIM), comes from Jeremiah 7:11, where the prophet asks, “Has this house…become a den of robbers in your sight?” Jesus changed Jeremiah’s rhetorical question to a straightforward indictment. The temple, which was intended to be a place where all peoples could worship, had degenerated into a place of profiteering. The message is obvious. But was this all Jesus was saying? Was he solely addressing the vendors and no other culpable party?

Reading the larger context of Jeremiah 7:11, one encounters the following:

Thus says the LORD of hosts, the God of Israel, “Amend your ways and your deeds, and I will let you dwell in this place…. Will you steal, murder and commit adultery, and swear falsely, and offer sacrifices to Baal, and walk after other gods that you have not known, then come and stand before Me in this house which is called by My name, and say, ‘We are delivered!’—that you may do all these abominations? Has this house, which is called by My name, become a den of robbers in your sight? Behold, I, even I, have seen it…. But go now to My place which was in Shiloh, where I made My name dwell at the first, and see what I did to it because of the wickedness of my people Israel…I will do to the house which is called by My name, in which you trust, and to the place which I gave you and your fathers, as I did in Shiloh.”[6]

The phrase “den of robbers” prompted the minds of the scribes and priests to supply the surrounding verses. Indeed, they were surprised. With two words, מְעָרַת פָּרִצִים (me·‘ā·RAT pā·ri·TZIM, “den of robbers”), Jesus not only addressed the merchants, whose interests were too focused on profits, but he censured the aristocratic, priestly authorities themselves. They were the root of the problem. The vendors were merely symptomatic of it. Lifting vocabulary from Jeremiah 7:11, which is followed by two verses where Shiloh is mentioned, Jesus hinted that the temple in Jerusalem would be destroyed just as the sanctuary at Shiloh had been.

Ruins at the site of Shiloh. Photo courtesy of BiblePlaces.com.

In Shiloh the two sons of Eli, Hophni and Phinehas, abused their priestly privileges. God’s wrath flared against the priests of the House of Eli with the result that Eli and his sons died on the day that Israel was defeated by the Philistines at Aphek.[7] Moreover, the biblical and archaeological records indicate that the Philistines continued their campaign and torched Shiloh.[8] An allusion to the impending destruction of the temple is the punch behind the two words, מְעָרַת פָּרִצִים (me·‘ā·RAT pā·ri·TZIM, “den of robbers”), which Jesus said that fateful day. More so than any other event recorded in the synoptic gospels, this incident just outside the temple courts contributed to Jesus’ death in Jerusalem. The temple authorities could not tolerate being denounced publicly by a Galilean sage behaving like a prophet. Their livelihood and basis of power were derived from the temple, and they were prepared to conspire against any who proclaimed its imminent ruin.[9]

The Connection

Of all the verses Jesus could have chosen, why did he juxtapose Isaiah 56:7 with Jeremiah 7:11? Other passages speak about the glory of the temple or how the people had profaned it. Such utterances are in no short supply in the mouths of the prophets. The key is likely the expression “my house,” בֵּיתִי (bē·TI). Jewish teachers in the time of Jesus were fond of juxtaposing passages that shared a common word or phrase. For example, in Luke 10:27 a lawyer combined Deuteronomy 6:5 and Leviticus 19:18. Both of these verses contain the phrase, וְאָהַבְתָּ (ve’ā·hav·TĀ, “and you shall love”). The appearance of ve’ā·hav·TĀ in both verses, although not the only reason, certainly helped inspire the lawyer to fuse them when responding to Jesus’ question, “What is written in the Torah?”

The same phenomenon occurs in Luke 19:46 with the expression “my house” (bē·TI). This expression is found in Isaiah 56:7. But does it appear in Jeremiah 7:11? The Hebrew Masoretic text, from which English translations of the Old Testament are made, reads, “this house,” הַבַּיִת הַזֶּה (ha·BA·yit ha·ZEH); however, the ancient Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible, known as the Septuagint[10] has, “my house,” ὁ οἶκός μου (ho oikos mou). This suggests that Jesus had learned Jeremiah 7:11 according to the tradition preserved in the Septuagint rather than that preserved in the Masoretic text—the shared expression “my house” would have been an attractive reason for Jesus to combine the verses.

Conclusion

This article has introduced the reader to two modes of scriptural interpretation that Jesus employed when teaching. Jesus liked to hint at a verse of Scripture by lifting vocabulary from it. By doing so, he was able to marshal the full force of the verse’s context with only a word or two.[11] Saying “den of robbers” was tantamount to saying that the temple would be judged like the holy site at Shiloh. This style of teaching presupposes a high level of scriptural literacy among the audience.[12] A second technique that Jesus employed in order to energize a verse of Scripture was to combine it with another verse that shared the same word or phrase. This gave new meaning to both verses, as each was understood afresh in the light of the other. In Luke 19:46 the common word also added cohesion to a stunning contrast, “My house is a house of prayer, but you have made my house a den of robbers!”

Living nearly twenty centuries after Jesus, Christians in the modern Western world can easily miss the subtleties of his teaching. There are daunting cultural, religious, and temporal ravines between today’s world and that which Jesus knew. Nevertheless, with a commitment to the biblical languages and texts of ancient Judaism, they can be bridged, and the freshness, genius, and, at times, shock of many of Jesus’ words can be reclaimed.

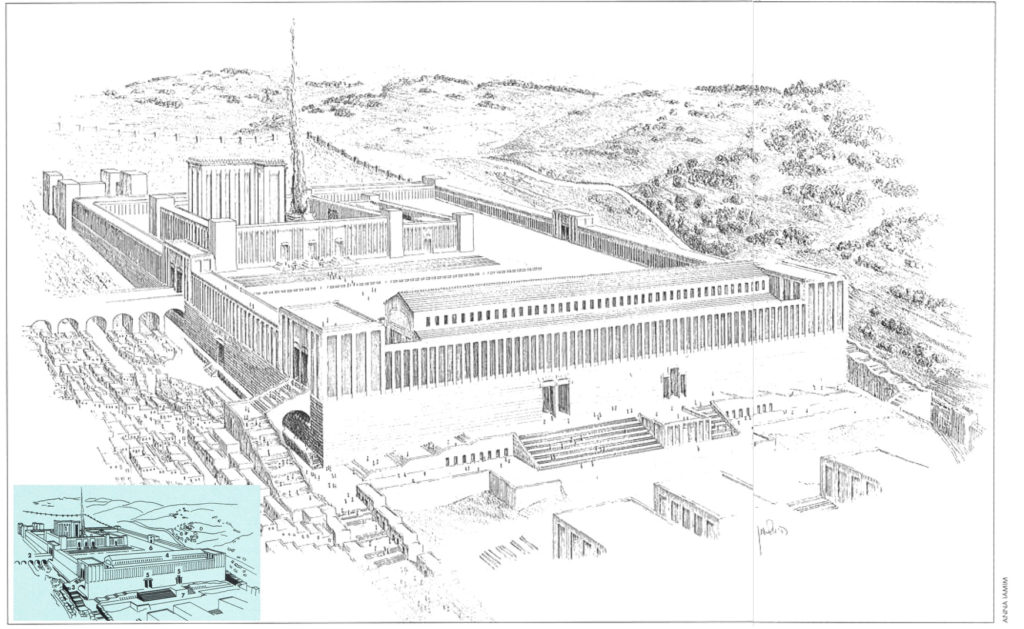

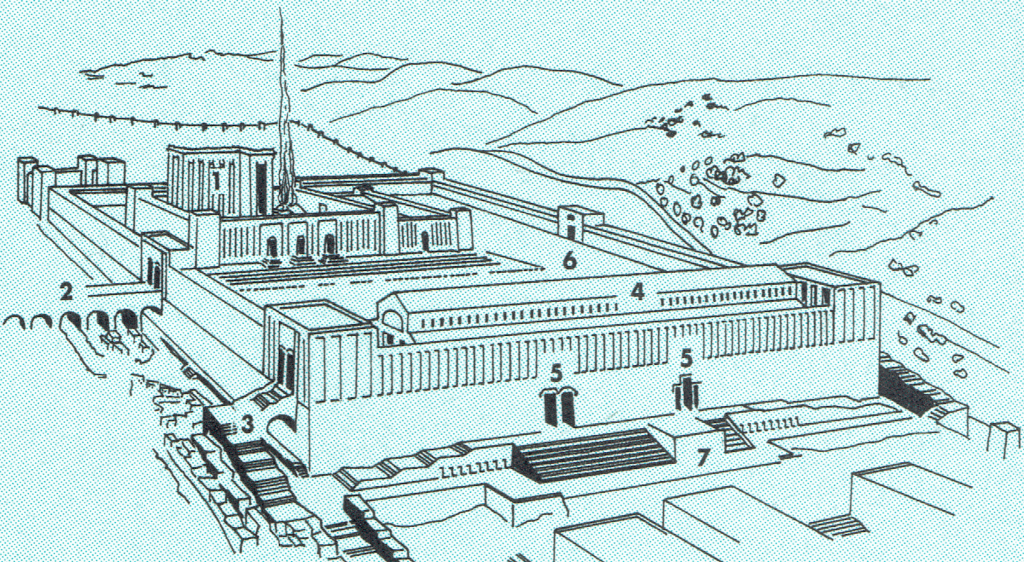

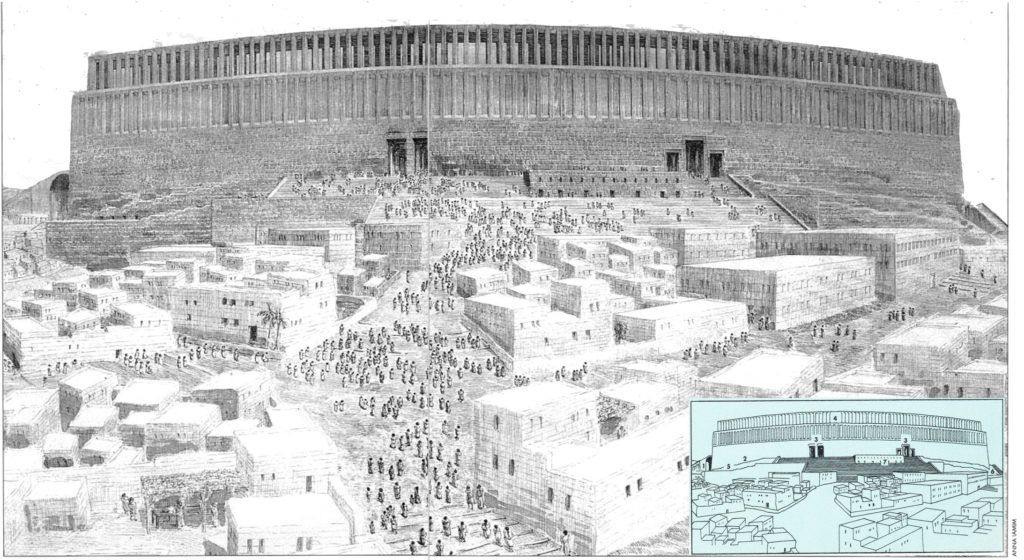

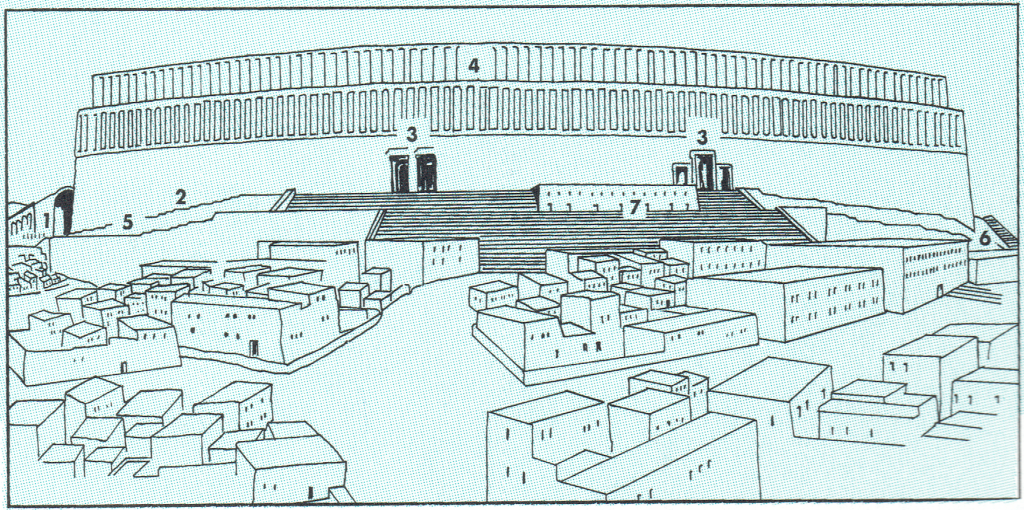

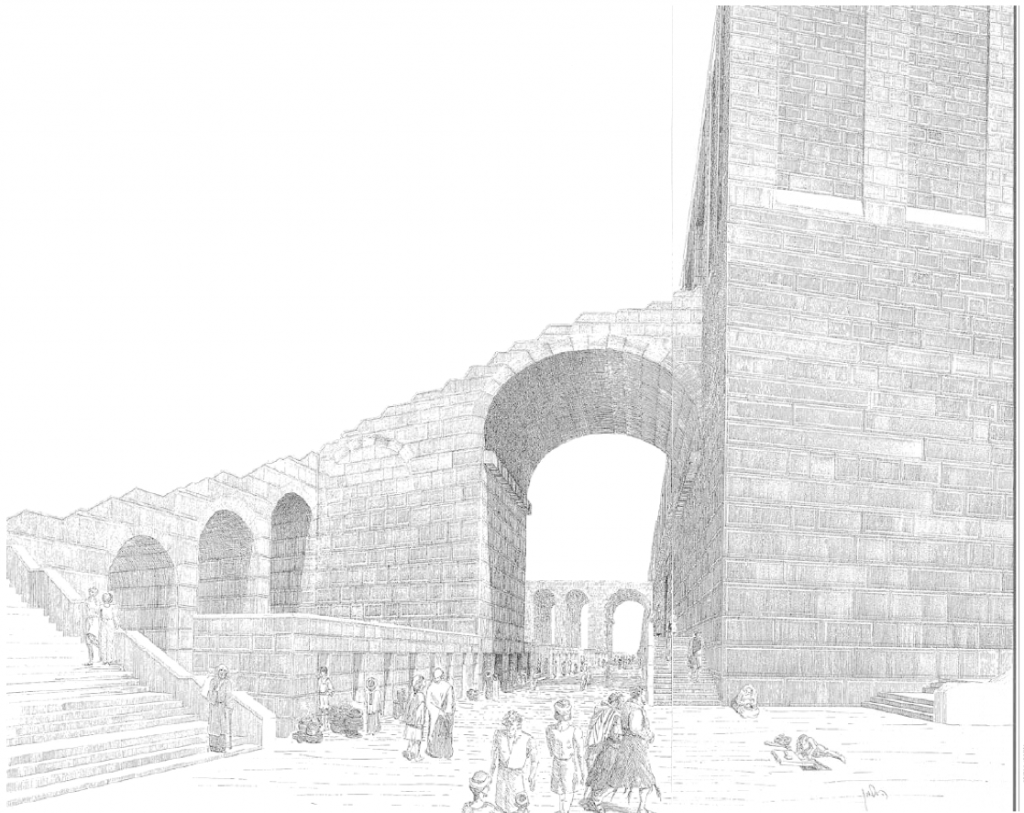

SIDEBAR: Where Were the Vendors?Nearly all New Testament commentaries identify the outer-most court of the temple, sometimes referred to as the Court of the Gentiles, as the location for the “Cleansing of the Temple” incident. It seems odd, however, that buying and selling would have been permitted even in this court. Professor Shmuel Safrai states that it is unthinkable that any commercial activity took place in the Temple courts, including the Court of the Gentiles. It was not even permitted to ascend the Temple Mount with a purse (Mishnah, Berachot 9:5). Safrai maintains that the most likely places for the “Cleansing” are the Royal Portico or the shops in the vicinity of the southern stairway (private communication). One would expect that worshippers approaching the temple first passed the vendors, then proceeded to public mikva’ot where they could ritually immerse, climbed the massive southern stairway, entered the Huldah Gates (compare Mishnah, Middot 1:3), and ascended an underground ramp from which they exited into the Court of the Gentiles. Shops built into vaults supporting a walkway running flush with the southern wall from its western to eastern corner have been found in archaeological excavations. The southern stairway ascended to this walkway opposite the Huldah Gates. The vendors mentioned in Luke 19:45 may have been conducting business in the shops built into the vaults adjacent to the stairway. (See Hillel Geva, “Jerusalem” in The New Encyclopedia of Archaeological Excavations in the Holy Land [Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society and Carta, 1993], 2:739-40.) Two other sites within the Temple environs where business transactions occurred were the halls of the Royal Portico and the shops around the base of Robinson’s Arch. (See Meir Ben-Dov, The Ophel Archaeological Garden [Jerusalem: East Jerusalem Development Ltd., 1987], 13-14.) |

Notes

- See Matt. 21:12-13; Mark 11:15-18; Luke 19:45-46; John 2:13-17. ↩

- Robert Lindsey believes that behind the Greek word ἐκβάλλειν (ekballein, to drive out,” “to expel”) is the Hebrew לְהוֹצִיא (le·hō·TZI’, “to bring out,” “to take out”). See his A Hebrew Translation of the Gospel of Mark (2nd ed.; Jerusalem: Dugith Publishers, 1973), 133; and Edwin Hatch and Henry A. Redpath, A Concordance to the Septuagint (Oxford: The Clarendon Press, 1897; repr. Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Book House, 1987), 1:420. The Syriac text of Luke 19:45 supports Lindsey’s view. Both the Old Syriac (Sinai Palimpsest) and Peshitta versions give the Aphel infinitive of the root נ-פ-ק (n-f-k) with a -ל (lamed) prefix. This is the Syriac equivalent of the Hebrew le·hō·TZI’.

Like ekballein, le·hō·TZI’ has a range of nuances. (See Walter Bauer, A Greek-English Lexicon of the New Testament and Other Early Christian Literature [4th ed., trans. and ed. William F. Arndt and F. Wilbur Gingrich; Chicago: University of Chicago Press, and Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1957], 236-37; and Marcus Jastrow, A Dictionary of the Targumim, the Talmud Babli and Yerushalmi, and the Midrashic Literature (repr. New York: Pardes Publishing House, 1950), 587-88.) The English translation, “to drive out,” though suitable at times for ekballein, is a bit strong for the Hebrew lehōtzi’. According to Luke’s account, Jesus did not forcefully drive out the vendors from the area. He may have expelled them (without resorting to brute force) or simply summoned them out of their shops where he began speaking to them and others who had gathered around. Mark’s overthrowing of tables and chairs (Mark 11:15) is probably an attempt to clarify which nuance of ekballein he wanted his readers to understand. Matthew followed Mark’s lead. The trend culminated with John’s description of Jesus driving out the people with a whip (John 2:15). After teaching publicly for some time, Jesus had become a highly respected moral figure. It was enough that he spoke in a stern manner. Note the way that Jesus handled the incident recorded in Luke 4:29-30, passing unharmed through the enraged residents of Nazareth. There was an aura of authority that accompanied Jesus’ presence. ↩

- See Alfred Plummer, A Critical and Exegetical Commentary on the Gospel According to St. Luke, in The International Critical Commentary (Edinburgh: T & T Clark, 1896), 453. ↩

- Another incident where Jesus is involved in a professional dialogue with a peer is the episode in Luke 10:25-37, where he tells the Parable of the Good Samaritan in order to clarify who is one’s neighbor. See Jacob Mann, “Jesus and the Sadducean Priests: Luke 10:25-37,” Jewish Quarterly Review 6 (1914): 415-422; and Brad H. Young, Jesus and His Jewish Parables: Rediscovering the Roots of Jesus’ Teaching (Mahwah, NJ: Paulist Press, 1989), 239-41, 269-70. ↩

- Isa. 56:6-7 from the New American Standard Bible. ↩

- Jer. 7:3, 9-11, 14 from the New American Standard Bible. ↩

- See 1 Sam. 4:1-22. ↩

- Compare Jer. 26:9 and Ps. 78:60. See Israel Finkelstein, “Shilo,” in The New Encyclopedia of Archaeological Excavations in the Holy Land (Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society and Carta, 1993), 4:1364, 1368. ↩

- The New Testament, Dead Sea Scrolls, Josephus and rabbinic literature indicate that the aristocratic high priests were motivated by self-interests. One cannot stress enough that it was they who persuaded the Romans to execute Jesus (cf. Luke 24:20). The priests who were responsible for Jesus’ arrest constituted a small circle of individuals (see David Flusser, “…To Bury Caiaphas, Not to Praise Him,”Jerusalem Perspective 33-34 [Jul.-Oct. 1991], 23-28). ↩

- The Septuagint dates from the second century B.C. ↩

- Compare Luke 11:20 and Exod. 8:19. Using the expression “finger of God,” Jesus cleverly rejoined those who were opposing him. Pagan magicians at Pharaoh’s court could recognize God’s power, but his opponents could not. (This example was brought to the author’s attention by Brad Young.) ↩

- Cf. Hayim Goren Perelmuter, Siblings: Rabbinic Judaism and Early Christianity at Their Beginnings (Mahwah, NJ: Paulist Press, 1989), 14. ↩