The late David Flusser was one of the world’s foremost Jewish authorities on the New Testament and early Christianity. The Sage from Galilee is Flusser’s biography of Jesus (written in collaboration with his student, R. Steven Notley). In this biography, Flusser tells what he learned in a lifetime of studying the life and teachings of Jesus of Nazareth.

The book is especially significant for researchers of the Synoptic Gospels because Flusser follows the synoptic theory of the late Robert Lindsey. Together, Flusser and Lindsey laid the foundations for a school of New Testament research, today known as the Jerusalem School of Synoptic Research. In the first chapter of the book (p. 4), Flusser states his intention to “apply the methods of literary criticism and Lindsey’ s [synoptic] solution to unlock these ancient sources [i.e., Matthew, Mark and Luke].”

In the Preface to Sage (pp. xviii-xix), Flusser writes:

I grew up in the strongly Catholic, Bohemian town of Príbram. The town was one of the great centers of pilgrimage in Central Europe. Because of the humane atmosphere in Czechoslovakia at that time, I did not experience any sort of Christian aversion to my Jewish background. In particular, I never heard any accusation of deicide directed against my people. As a student at the University of Prague, I became acquainted with Josef Perl, a pastor and member of the Unity of Bohemian Brethren, and I spent many evenings conversing with him at the local YMCA in Prague. The strong emphasis which this pastor and his fellow brethren place on the teaching of Jesus and on the early, believing community in Jerusalem stirred in me a healthy, positive interest in Jesus, and influenced the very understanding of my own Jewish faith as well. Interacting with these Bohemian Brethren played a decisive role in the cultivation of my scholarly interests; their influence was one of the foremost reasons that I decided to occupy myself with the person and message of Jesus.

Later in life I became interested in the history of the Bohemian Brethren, and I discovered links between this group and other similar movements in the past and present. I have since had the honor to become acquainted with members of one such movement having spiritual links to the Bohemian Brethren—the Mennonites in Canada and the United States. When my German book on Jesus was first published, a leading Mennonite asked me if the book were Christian or Jewish. I replied, “If the Christians would be Mennonites, then my work would be a Christian book.” What I have set out to do here is to illuminate and interpret, at least in part, Jesus’ person and opinions within the framework of his time and people. My ambition is simply to serve as a mouthpiece for Jesus’ message today.

Here is an excerpt from “Love,” Chapter 5 of Sage (pp. 55, 57, 60):

The germ of revolution in Jesus’ preaching does not emerge from his criticism of Jewish law, but from other premises altogether. These premises did not originate with Jesus. On the contrary, his critical assault stemmed from attitudes already established before his time. Revolution broke through at three points: the radical interpretation of the commandment of mutual love, the call for a new morality, and the idea of the kingdom of heaven….

Luke 6:36 is a parallel to Matthew 5:48: “You must be perfect, as your heavenly Father is perfect.” The best way of translating this saying is, “There must be no limit to your goodness, as your heavenly Father’s goodness knows no bounds” [New English Bible]. Matthew 5:48 is merely the conclusion to a short homily where Jesus teaches that God reaches out in love to all people, regardless of their attitude and behavior toward him, “for he makes his sun rise on the evil and on the good, and sends rain on the just and on the unjust.” In this Jesus is not far from the humane attitude of other Jews. Rabbi Abbahu said, “Greater is the day of rainfall than the day of resurrection. For the latter benefits only the pious, whereas the former benefits pious and sinners alike” [b. Ta’anit 7a]. Rabbi Abbahu lived about 300 A.D., but there is a similar saying dating from Jesus’ time. Thus, it is no wonder that in such a spiritual atmosphere Jesus drew his daring conclusion: “Love your enemies!” (Matt. 5:44). In other words, “Return love to those who hate you” or: “Do good to those who hate you” (Luke 6:27)….

A man’s relationship to his neighbor ought, therefore, to be determined by the fact that he is one with him both in his good and in his evil characteristics. This is not far from Jesus’ commandment to love, but Jesus went further and broke the last fetters still restricting the ancient Jewish commandment to love one’s neighbor. We have already seen that Rabbi Hanina believed that one ought to love the righteous and not hate the sinner. Jesus said, “I say to you, Love your enemies and pray for those who persecute you” (Matt. 5:44). It is true that in those days semi-Essene circles had reached similar conclusions from different presuppositions, and Jesus’ moral teaching was influenced by these circles. Yet, influences do not explain everything.

Following is an excerpt from “Ethics,” Chapter 6 of Sage (p. 75):

On one occasion someone brought the news to Jesus about the Galileans whose blood Pilate mixed with their sacrifices…. It was then, more or less, a general opinion that calamity—and illness—was a punishment for sin. It could be argued, therefore, that these men were greater sinners than other Galileans. Jesus did not reject this general opinion, but at the same time he rejected the current application of this view as simplistic. Instead of the vulgar ethics, he called to Israel, “Repent or perish!” He illustrated his call for a national repentance by the following parable of the barren fig tree (Luke 13:6-9). Later on, being in Jerusalem he saw the imminent catastrophe as almost inevitable (Luke 19:40-41). The future destruction of Jerusalem could have been avoided, if it had chosen the way of peace and repentance.

Jesus’ concept of the righteousness of God, therefore, is incommensurable with reason. Man cannot measure it, but he can grasp it. It leads to the preaching of the kingdom in which the last will be first, and the first last. It leads also from the Sermon on the Mount to Golgotha, where the just man dies a criminal’s death. It is at once profoundly moral, and yet beyond good and evil. In this paradoxical scheme, all the “important,” customary virtues, and the well-knit personality, worldly dignity, and the proud insistence upon the formal fulfillment of the law, are fragmentary and empty. Socrates questioned the intellectual side of man. Jesus questioned the moral. Both were executed. Can this be mere chance?

Grand Rapids, Michigan: Eerdmans, 2007.

Here is an excerpt from “The Kingdom of Heaven,” Chapter 7 of Sage (pp. 80-82):

For Jesus and the rabbis, the kingdom of God is both present and future, but their perspectives are different. When Jesus was asked when the kingdom was to come, he said, “The kingdom of God is not coming with signs to be observed; nor will they say, ‘Lo, here it is!’ or ‘There!’ For behold, the kingdom of God is in the midst of you” (Luke 17:20-21). Elsewhere he said, “But if it is by the finger of God that I cast out demons, then the kingdom of God has come upon you” (Luke 11:20). According to Jesus, therefore, there are individuals who are already in the kingdom of heaven. This is not exactly the same sense in which the rabbis understood the kingdom. For them the kingdom had always been an unchanging reality, but for Jesus there was a specific point in time when the kingdom began to break out upon earth. “From the days of John the Baptist until now the kingdom of heaven is breaking through, and those who break through, seize it” (Matt. 11:12). According to Luke 16:16, “every one forces his way in.” Both of these dominical sayings reflect an ancient Jewish homily on Micah 2:13.

This, then, is the “realized eschatology” of Jesus. He is the only Jew of ancient times known to us who preached not only that people were on the threshold of the end of time, but that the new age of salvation had already begun…. for Jesus, the kingdom of heaven is not only the eschatological rule of God that has dawned already, but a divinely willed movement that spreads among people throughout the earth. The kingdom of heaven is not simply a matter of God’s kingship, but also the domain of his rule, an expanding realm embracing ever more and more people, a realm into which one may enter and find one’s inheritance, a realm where there are both great and small. That is why Jesus called the twelve to be fishers of men [Matt. 4:19] and to heal and preach everywhere. “The kingdom of heaven is at hand” (Matt. 10:5-16). For this reason he demanded of some that they should leave everything behind and follow him. We do not mean to assert that Jesus wanted to found a church or even a single community, but that he wanted to start a movement. Stated in exaggerated ecclesiological terms, we might say that the eruption of the kingdom of heaven is a process in which ultimately the invisible Church becomes identical with the visible.

That which Jesus recognized and desired is fulfilled in the message of the kingdom. There God’s unconditional love for all becomes visible, and the barriers between sinner and righteous are shattered. Human dignity becomes null and void, the last become first, and the first become last. The poor, the hungry, the meek, the mourners, and the persecuted inherit the kingdom of heaven. In Jesus’ message of the kingdom, however, the strictly social factor does not seem to be the decisive thing. His revolution has to do chiefly with the transvaluation of all the usual moral values, and hence his promise is specially for sinners. “Truly, I say to you, the tax collectors and the harlots go into the kingdom of God before you” (Matt. 21:31-32). Jesus found resonance among the social outcasts and the despised, just as John the Baptist had done before him.

Even the non-eschatological ethical teaching of Jesus can presumably be oriented toward his message of the kingdom. Since Satan and his powers will be overthrown and the present world-order shattered, it is to be regarded almost with indifference, and ought not to be strengthened by opposition. Therefore, one should not resist evildoers; one should love one’s enemy and not provoke the Roman Empire to attack. For when the kingdom of God appears, all this will vanish.

Finally, here is an excerpt from “Death,” Chapter 11 of Sage (pp. 144-145):

I am convinced that there are reliable reports that the Crucified One “appeared to Peter, then to the twelve. Then he appeared to more than five hundred brethren at one time…. Then he appeared to James, then to all the apostles.” Last of all, he appeared to Paul on the road to Damascus (1 Cor. 15:3-8). When Jesus answered the high priest’s question about his Messiahship with the words, “From now on the Son of Man shall be seated at the right hand of the power of God,” did he believe that he would escape the fate that threatened him? Or, as is more likely, did he believe that he would rise from the dead? In any event, the high priest correctly understood that by Jesus’ words he was confessing that he was the Messiah. Therefore they said, “What need have we of further witnesses? You have heard it from his own mouth” (Luke 22:71). Jesus was taken straightway to Pilate.

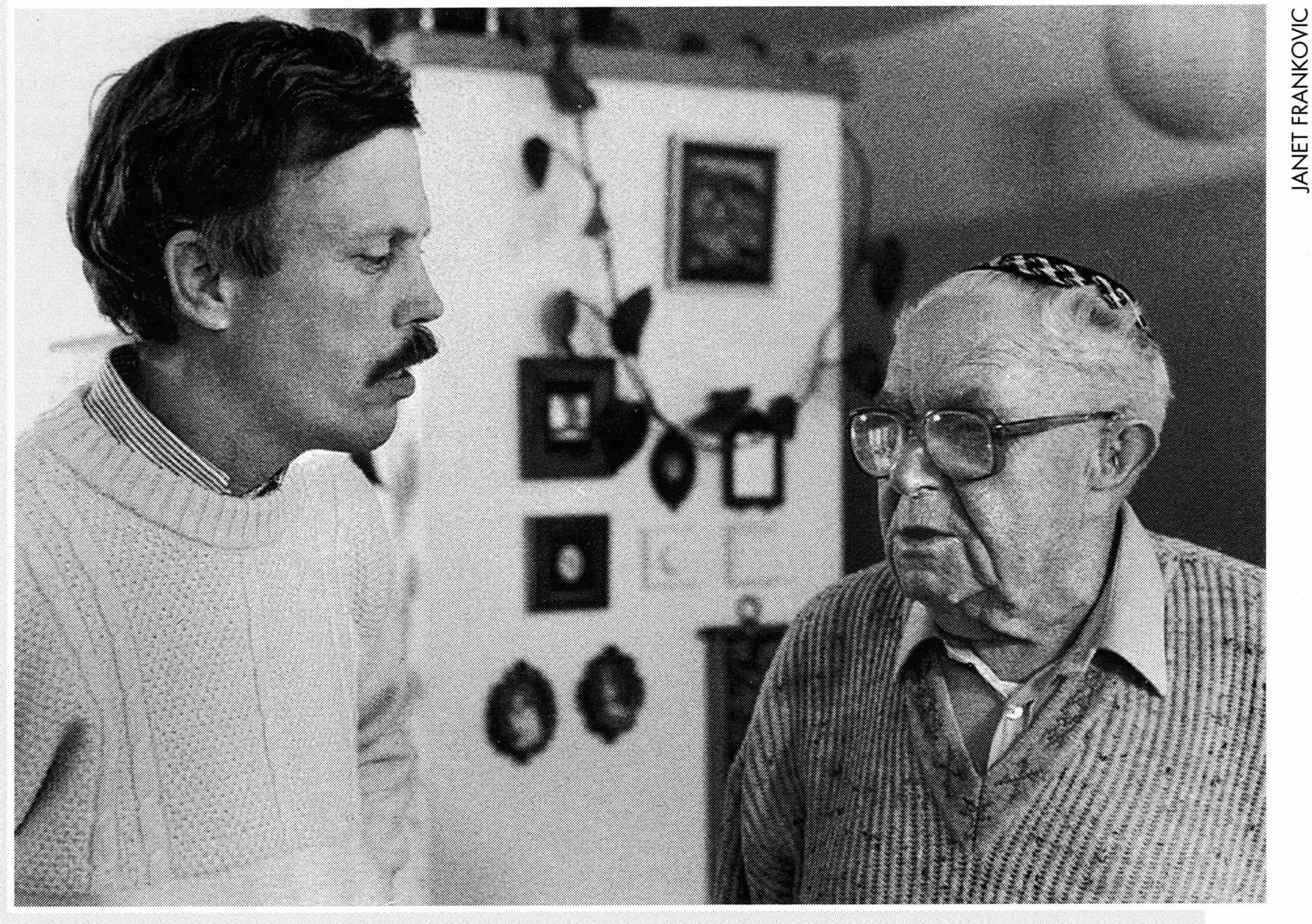

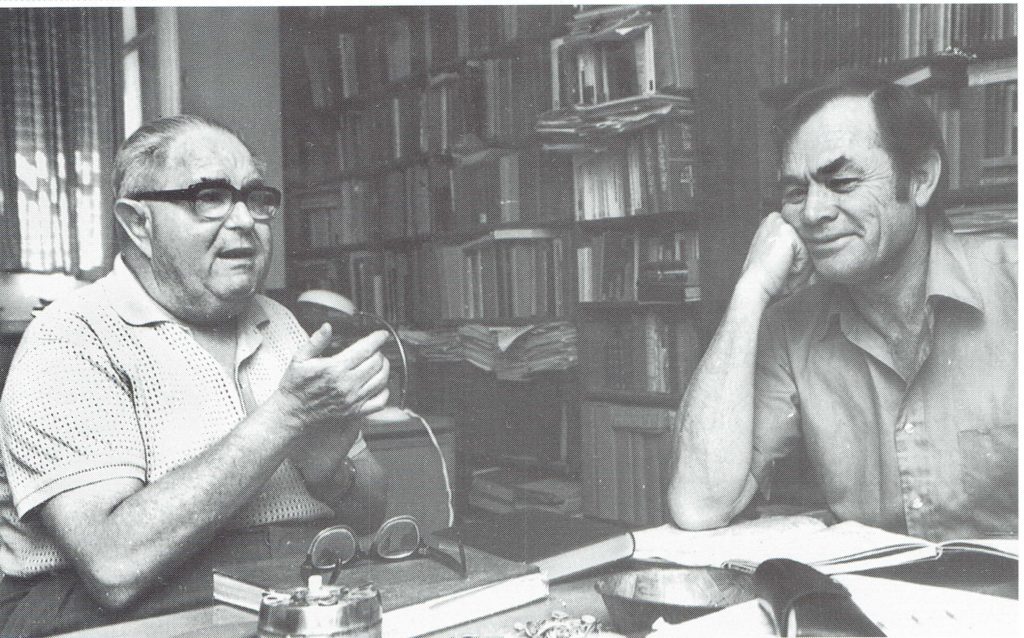

![David Flusser [1917-2000]](https://www.jerusalemperspective.com/wp-content/uploads/userphoto/21.jpg)