Question received from Mary R. Carse that was published in the “Readers’ Perspective” column of Jerusalem Perspective 46 & 47 (Sept.-Dec. 1994): 6.

According to Leviticus 12, the presenting of the two turtledoves constituted the purification for childbirth. And in fact, the same thing seems to be implied concerning a woman’s menstrual period (Lev. 15:19ff.). Anyone who touches her or anything she has touched has to purify himself by washing, but nothing seems to be said about the woman washing herself at any time, either after childbirth or after her monthly period. So where did the idea of the mikveh come from? Was that a later introduction? Still, I know that mikva’ot [plural of mikveh] have been excavated at the base of the steps on the south side of the Temple Mount which led up to the Temple. What were they for? And if a woman had to present an offering for her purification both after childbirth and after her monthly period, did she have to travel all the way to Jerusalem every month?

Shmuel Safrai responds:

It was not necessary for Mary to go immediately from Nazareth in Galilee to Jerusalem to offer the sacrifice for her purification. To quote from my daughter Chana Safrai’s article, “Jesus’ Devout Jewish Parents and Their Child Prodigy”:

According to Scripture, a mother is impure for forty days after the birth of a son. At the end of this period, she is to bring to the Temple an offering for her purification (Lev. 12:1-8). Rabbinic sources indicate that a woman was allowed to postpone her sacrifice until she had an opportunity to go to Jerusalem. Sometimes a mother waited until she had given birth a number of times before offering the prescribed sacrifice for her purification (Tosefta, Keritot 2:21; Mishnah, Keritot 1:7, 2:4). Often, she waited to fulfill this obligation until the family made a pilgrimage to Jerusalem. However, some women performed this rite at the end of the forty-day period in keeping with the biblical injunction. Mary observed the commandment in this way.

As Chana points out, a mother could postpone the prescribed sacrifice after the birth of a son; however, she could not postpone the ritual immersion. Therefore, this was usually done at the local mikveh in the woman’s hometown. It was not necessary for a woman to travel to the Temple in Jerusalem for the immersion. As Mary Carse has supposed, women were also required to immerse themselves after the menstrual period, and this, too, was done at a local mikveh. It is true that nothing seems to be said in the Torah about a woman’s requirement for immersion after the birth of a son and following menstruation, but the sages viewed immersion in these cases as scriptural commandments. They based this view on their understanding of Leviticus 12:1-8; 15:18; and 18:19. (For further details of the sages’ view, see the discussions in Mishnah tractate Niddah.)

Just when in history the mikveh came into being we do not know; however, it is certain that its use was already well-established in Jewish society by Jesus’ time. Immersion as part of a woman’s purification was also practiced by Essenes and Samaritans.

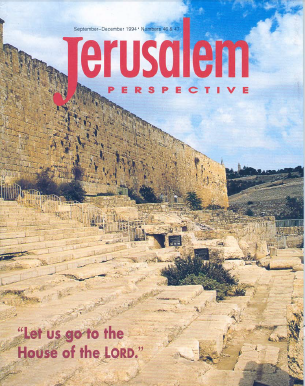

Large ritual immersion pool (mikveh) at the Temple Mount—possibly used by priests for their ritual washing. Photograph by Todd Bolen courtesy of BiblePlaces.com.

The mikva’ot adjacent to the monumental stairs leading to the south entrance of the Temple Mount were used by persons who intended to enter the inner courts of the Temple. One could ascend the Temple Mount and visit the outer court (the so-called Court of the Gentiles) without having to purify oneself in a mikveh, if one did not proceed beyond the Court of the Gentiles. In fact, if in a state of ritual cleanness, a Jew could even enter the Women’s Court, the outer court of the sanctuary, without undergoing ritual immersion. However, to proceed further (to the Israelites’ Court and beyond), he or she had to bathe in a mikveh, even if ritually clean. There was a mikveh located in the Lepers’ Chamber, in the northwest corner of the Women’s Court (Mishnah, Middot 2:5; Negaim 14:8), and there were many other mikva’ot scattered over the Temple Mount. These were not just for the priests, who served in the inner courts of the Temple, but also for non-priests—when offering their sacrifices, non-priests could enter the Priests’ Court (Jerusalem Talmud, Yoma III, 40b).

Gentiles could also ascend the Temple Mount; however, they were not permitted to enter the sanctuary itself. On all four sides of the sanctuary was an ascent of fourteen steps and a five-meter-wide walkway or rampart (in Hebrew, Hel) immediately adjoining the outside walls of the sanctuary. Encircling these stairs and walkway was a stone balustrade (1.5 meters in height), called in Hebrew, the Soreg. Gentiles could not go beyond this barrier and, according to Josephus (War 5:195–197; Antiq. 15:417; cf. Mishnah, Kelim 1:8), there were warning signs in Greek and Latin affixed to the Soreg at regular intervals forbidding Gentiles, under penalty of death, to proceed further. Two of these signs written in Greek (one complete, and one partially preserved), have been discovered in Jerusalem.

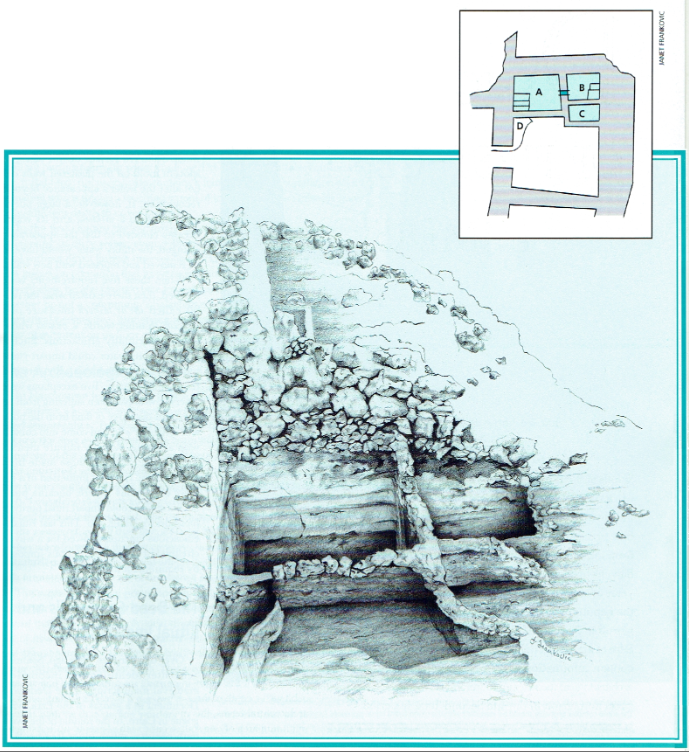

Masada’s southern mikveh (of the rain-fed, double-chambered design. Top Right: Plan of the southern mikveh at Masada: A. Rainwater collection pool (dormant chamber); B. Active immersion chamber; C. Pool for washing of hands and feet; d. Settling trough. Illustration: Janet Frankovic

To make sure that no one willfully or inadvertently violated the purity regulations, Levites were appointed as supervisors. (Remember that the Levites were the Temple gatekeepers.) We learn this from, among others, the first-century Jewish historian Philo (On the Special Laws 1:156). The Levites conducted spot-checks, asking people entering the Temple whether they were ritual clean, or, in the case of persons entering the Israelites’ Court, whether they had bathed in a mikveh. In addition, it was required of worshippers that they ascend the Temple Mount with freshly washed white garments and barefooted (War 2:1).

In a third-century C.E. fragment of a non-canonical gospel written in Greek (Oxyrhynchus Papyri V, 840), there is a very interesting tradition about Jesus. According to this source, Jesus and his disciples were accosted in the Temple by a Levite supervisor and accused of having violated the purification regulations:

“Who has given you permission to walk in this holy place and to look upon these holy vessels without first bathing yourself and even without your disciples having washed their feet, but in an unclean state you have walked in this holy and purified place, although no one who has not first bathed himself and changed his clothes may walk in it and venture to view these holy vessels.”Jesus replied, “I am clean, for I have bathed myself in the pool of David. I have gone down [into it] by the one stair and come up [out of it] by the other, and I have put on white garments that are ritually clean, and in that state I have come here and looked upon these holy vessels.”

While this story about Jesus may not be historical, much authentic detail about the customs of those who came to the Temple is preserved in this fragment, such as the changing of one’s clothes, the wearing of white clothes and the ritual bathing before entering the Temple. This source contains authentic Jewish traditions from the first century C.E. These traditions cannot be literary inventions. A third-century Gentile author would not likely have known, for instance, that on every Jewish pilgrimage festival, the holy Temple utensils were brought out and put on display in the Israelites’ Court for the benefit of visiting pilgrims.

![Shmuel Safrai [1919-2003]](https://www.jerusalemperspective.com/wp-content/uploads/userphoto/20.jpg)