In the Gospel of Luke we find an interesting sequence of verses:

.

The men of Nineveh shall stand up with this generation at the judgment and condemn it, because they repented at the preaching of Jonah. And behold, something greater than Jonah is here. No one, after lighting a lamp, puts it away in a cellar, nor under a peck-measure, but on the lampstand, in order that those who enter may see the light. The lamp of your body is your eye. When your eye is clear, your whole body also is full of light, but when it is bad, your body also is full of darkness. (Luke 11:32-34)

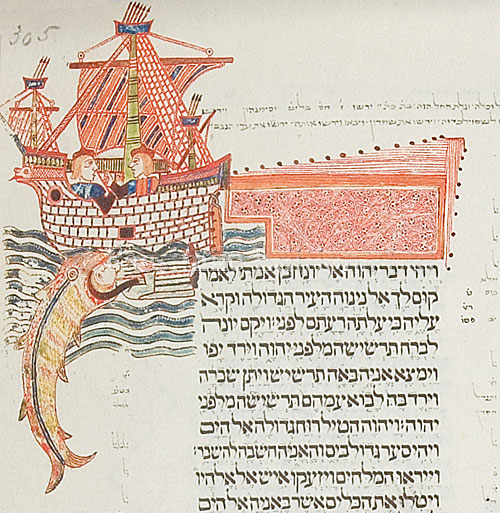

What is the relationship between the preaching of Jonah and putting a lamp on a lampstand? The prophet Jonah in classical Jewish thought calls to mind repentance. In Rabbinic literature we read that many prophets were sent to Jerusalem and the people did not listen, but to Nineveh one prophet was sent, and the people repented.[1]

The sign of Jonah indicated repentance. In fact, during public fasts in ancient Israel the Torah ark was wheeled out into the city square. An elder then addressed the people with these words, “Brethren, it does not say about the men of Nineveh that God saw their sack cloth and fasting, but that God saw their deeds, that they had turned from their wicked ways.”[2]

In the same context as the men of Nineveh, Jesus also mentioned the Queen of the South. What business does the Queen of the South have with the men of Nineveh? The queen and the Ninevites were Gentiles, which to a Jew living in the first century meant that they were sinners (cf. Galatians 2:15). As sinners, no Jew had any serious expectations of them in terms of spirituality or piety. Nevertheless, the Queen of the South and the Ninevites responded to God in a manner that surpassed expectations.

Two verses follow which mention the Greek word luxnos[3] (or “lamp” in English). Verse 33 says: “No one after lighting a lamp, puts it away in a cellar, nor under a peck-measure, but on the lampstand…” Verse 34 adds, “The lamp of your body is your eye; when your eye is clear, your whole body is also full of light…”

Once when teaching about treasures in heaven, I asked the audience the following question: “If I were to assign the task of preaching a sermon from these verses, what would you preach?” One person immediately commented that the content of Luke 11:33 appears also in Matthew 5:15. His textual instincts had told him to flee from this awkward Lukan passage and consult the Matthean parallel. Approaching the text in such a manner reflects textual-critical thinking. This person recognized the difficulty of interpreting the Lukan passage, and before expounding the text, he felt a need to look at the Matthean parallel.

I designed this short exercise in textual criticism in order to demonstrate the importance of giving thought to which version of a passage in Matthew, Mark, and Luke we rely upon as we prepare to preach or teach. Luke 11:33, which reads, “No one, after lighting a lamp, puts it away…,” is repeated in Matthew 5:15. In Matthew 5:14 Jesus declared, “You are the light of the world…” In Matthew 5:13 he declared, “You are the salt of the earth….” Jesus envisaged his disciples to be like light and salt. In other words, they were to be distinct. These Matthean verses constitute the longer, original context to which Luke 11:33 once belonged.

Luke 11:34, which says, “the lamp of your body is your eye,” is repeated in Matthew 6:22. The Matthean context is a homily about money. Here Luke 11:34 makes better sense because in Hebrew the idiom, “good eye,” means generosity.[4] When reading the synoptic gospels, checking parallel passages is important. Sometimes it makes a significant difference in exegesis.

Jesus on Long-term Investing

We will now direct our attention to the full context of Matthew 6:22 (and Luke 11:34):

Do not lay up for yourselves treasure on earth, where moth and rust consume, and where thieves break in and steal. But lay up for yourselves treasure in heaven, where neither moth nor rust consumes, and where thieves do not break in and steal. For where your treasure is, there will your heart be also. The eye is the lamp of the body. So, if your eye is sound, your whole body will be full of light. But, if your eye is not sound, your whole body will be full of darkness. If then, the light in you is darkness, how great is the darkness! No one can serve two masters, for either he will hate the one and love the other, or he will be devoted to the one and despise the other. You cannot serve God and mammon.

Matthew 6:19-24 represents a homily on maintaining a proper attitude toward money. Luke, however, has dispersed the same homiletic material throughout his gospel. For example, Matthew 6:19-21 parallels Luke 12:33, 34, Matthew 6:22, 23 parallels Luke 11:34-36, and Matthew 6:24 parallels Luke 16:13, which comes after the Parable of the Unrighteous Steward.[5]

Ben Sirach on Laying Up Treasure

In the Apocrypha[6] we find parallels to the phrase “laying up treasures in heaven.” I will quote two of them. The first comes from the Wisdom of Ben Sirach, which was written nearly two centuries before the birth of Jesus:

Help a poor man for the commandment’s sake, and because of his need do not send him away empty. Lose your silver for the sake of a brother or a friend, and do not let it rust under a stone and be lost.[7] Lay up your treasure according to the commandments of the Most High, and it will profit you more than gold. Store up almsgiving in your treasury, and it will rescue you from all affliction; more than a mighty shield and more than a heavy spear, it will fight on your behalf against your enemy.[8]

This passage challenges the reader to lay up treasure according to the commandments of the Most High. That reminds us of Jesus’ words in Matthew 6:20, “But lay up for yourselves treasures in heaven, where neither moth nor rust destroys, and where thieves do not break in and steal!” Note also Ben Sirach’s exhortation, “Store up almsgiving in your treasury, and it will rescue you from all affliction.” In this sentence, he may have been hinting at Proverbs 10:2: “The treasuries of the wicked are of no benefit, but righteousness rescues from death.” Underneath the English translation “righteousness” stands the Hebrew noun tsedakah,[9] which in the biblical period generally meant “righteousness.”

During the centuries between the Old and New Testaments, the Hebrew language evolved. Some words that had meant one thing in the biblical Hebrew now could mean another in the mishnaic Hebrew. The Hebrew noun tsedakah serves as an excellent example of linguistic development between the biblical and mishnaic periods. In the mishnaic Hebrew, tsedakah may mean more than “righteousness”; it often meant “almsgiving.” Consequently, Proverbs 10:2 was understood as a reference to almsgiving.[10] In the first century A.D., a Jew would have translated this verse into English as “charity rescues from death.” I suspect that Ben Sirach had Proverbs 10:2 in mind when he wrote, “…it [almsgiving] will rescue you from all affliction.”[11]

Using Proverbs 10:2 as an example, I have tried to offer a glimpse of the manner in which Jews in Jesus’ day read their Bible. This endeavor is significant because their emphases were not always our emphases. Their preaching and teaching did not sound like our preaching and teaching. And, obviously, their word studies did not resemble our word studies. Moreover, when reading the New Testament, we encounter subjects for which little or no explanation is offered. The writers of the New Testament did not bother to explain certain concepts, because they assumed that their audiences were familiar with them. Examples of such concepts include marriage,[12] the Kingdom of Heaven, and, of course, treasures in heaven. An example is laying up treasures in heaven. First century Jews were very familiar with this idea. For them, treasures in heaven represented a sort of technical phrase and, therefore, required no explanation.

Tobit on Laying Up Treasure

A second parallel comes from another pre-Christian, apocryphal book called Tobit. It, too, is found in versions of the Bible prepared by the Catholic and Eastern Orthodox Churches:

Give alms from your possessions to all who live uprightly, and do not let your eye begrudge the gift when you make it. Do not turn your face away from any poor man, and the face of God will not be turned away from you.

The warning, “Do not turn your face away from any poor man, and the face of God will not be turned away from you” represents an example of a principle known in Hebrew as midah keneged midah. This literally means, “measure for measure.” In Modern English, the same idea may be expressed by the aphoristic sayings “reaping what one sows” and “what goes around comes around.”

What passages from the Bible would generate this identification of God with the poor? I am reminded of Isaiah 57:15 and 58:6-11, and Psalms 34:18. The psalmist sang that the Lord is near to the brokenhearted and saves the crushed in spirit. In a similar vein, Isaiah preached that God dwells with the crushed and lowly of spirit. Thus, the Bible clearly affirms the closeness of the Divine Presence to the lowly, the oppressed and the crushed.

Now we can more clearly see how the principle of midah keneged midah finds expression in this passage. The writer of Tobit was drawing from a complex of verses in the Bible, where God affiliates with the poor, downtrodden and crushed. Because God so closely identifies himself with such people, to turn away from the poor is tantamount to turning one’s back on God. This conclusion gains strength from the logical implications of Proverb 19:17: “He who is gracious to a poor man lends to the Lord, and he will repay him for his good deed.” The proverb indicates that God has rated the poor as a wise investment. More subtle, but just as significant, one who turns away the poor, rejects God and considers him a bad credit risk.

The passage in Tobit continues: “If you have many possessions, make your gift from them in proportion; if few, do not be afraid to give according to the little you have.” Tobit’s ethical advice to his son Tobias contains a very early expression of an idea which has become central to Jewish teaching on charity: a person who receives alms is himself required to give alms to another who is less fortunate than he. Approximately six hundred years after the writing of Tobit, the exilarch Mar Zutra declared, “A poor man who sustains himself by receiving charity, even he will give charity to another.”[13]

Luke wrote that Jesus once looked up and saw the rich putting their gifts into the temple treasury (Luke 21:1-4). Then a poor widow came and deposited two copper coins. That caught Jesus’ attention. This poor widow certainly stood as a candidate herself for receiving assistance. Nevertheless, she felt obliged to donate to the temple treasury. Perhaps some ethical instruction similar to Tobit’s echoed in her mind: “Fear not to give according to the little you have.” From this perspective, Jesus’ pointed remark may have been just as much a comment on the charitable under-achievement of the rich as it was on the over-achievement of the widow. She had acted in accordance with what she had been taught. Although the gifts from the rich may have been large, proportionally speaking, the widow’s two copper coins dwarfed their gifts.

Tobit continued his exhortation:

So you will be laying up a good treasure for yourself against the day of necessity. For charity delivers from death and keeps you from entering the darkness; and for all who practice it charity is an excellent offering in the presence of the Most High.[14]

Here we see a definite allusion to Proverbs 10:2: The Hebrew tsedakah (righteousness) from Proverbs 10:2 was translated in the Greek version of the Old Testament, otherwise known as the Septuagint, as dikaiosunae, which in Koine Greek may mean almsgiving. Interestingly, this passage from Tobit reads very closely to the Septuagint’s Greek version of Proverb 10:2.[15] The manner in which the author of Tobit alluded to Proverbs 10:2 indicates that Jews in Jesus’ day understood the proverb to mean “charity delivers from death.”[16]

We have surveyed these two passages from the Apocrypha for the sake of proper orientation. Ancient Jews placed a premium on charitable deeds. Moreover, reading their Bibles in a manner that accentuated the importance of such deeds, they discovered almsgiving and other charity-related activity throughout the Bible in places (such as Proberbs 10:2) where we as modern readers would not anticipate finding it.

Monobazus on Laying Up Treasure

Rabbinic literature contains a wonderful story about laying up treasures in heaven. In the first century A.D., Helena, Queen of Adiabene in northern Mesopotamia, and her son Izates, as Josephus called him, converted to Judaism. At a time of famine in Judea, this royal family purchased grain from Alexandria as well as dried figs from Cyprus, and sent these along with large sums of money to Jerusalem for relief of the poor. Apparently, this was the famine Luke mentioned in Acts 11:27-30. In the rabbinic version of the story, Monobazus, King of Adiabene, the brother of Izates and son of Helena, is singled out as the hero.[17]

According to the rabbis, an argument ensued when relatives learned about the great sums of money the king had spent to feed the starving inhabitants of Jerusalem. His response to his charitably challenged relatives was: “My fathers hoarded their treasures in storehouses here on earth, but I am depositing them in storehouses in heaven.”

The fame of the royal family of Adiabene endures even in our day. In 1863 the French archaeologist F. de Saulcy excavated a majestic tomb in East Jerusalem. The tomb’s grandeur suggested to him that it may have belonged to the kings of Judah, hence its name Tomb of the Kings. Later investigation revealed, however, that this tomb belonged to Queen Helena whose bones, according to Josephus, had been buried there.[18]

New Testament Writers on Laying Up Treasures

As part of a caveat issued against avarice, the epistle writer James mentioned laying up treasures in heaven, but with a negative application. James 5:1-3 says:

Come now, you rich, weep and howl for your miseries which are coming upon you. Your riches have rotted and your garments have become moth-eaten. Your gold and silver have rusted; and their rust will be a witness against you and will consume your flesh like fire. It is in the last days that you have stored up your treasure!

James was warning people who had pursued a life of opulence that their riches would not endure. Apparently ignoring Jesus’ advice, they had laid up for themselves treasures on earth, where rust and moth consume.

What about the apostle Paul? Although in his extant writings he did not use the phrase “treasures in heaven” or the accompanying imagery of gold rusting and moths consuming, he did not neglect such a foundational Jewish concept as almsgiving in his teachings. A modern reader might conclude otherwise because Paul expended considerable energy explaining the “mystery”[19] of the gospel and preaching and teaching about the Kingdom of Heaven and Jesus.[20] A revolutionary concept, the mystery of the gospel centered around Paul’s claim that God was now placing his Holy Spirit on uncircumcised Gentiles and extending to them the privilege of being grafted into the redemptive heritage of Israel.

A Digression on the Mysteries of the Gospel

Conventional Jewish thinking wrestled with this proposition. Jesus’ messianic claims were not solely, and perhaps not even primarily, responsible for early Rabbinic Judaism’s distancing of itself from the followers of the Way. Throughout the Book of Acts, the apostles are described functioning within the parameters of Judaism. Prior to Stephen’s stoning at the hands of diaspora Jews belonging to the Freedmen Synagogue and the scattering of the Jerusalem Church throughout Judea and Samaria, the esteemed Pharisee Gamaliel came to the apostles’ defense. His wise advice was, “…stay away from these men and let them alone, for if this plan…is of God, you will not be able to overthrow them” (Acts 5:38-39). Later, when a riot erupted on the Temple Mount, Jews from Asia accused Paul of preaching against the Law and bringing Greeks into the temple (Acts 21:28). They did not mention anything about Jesus. The source of tension ultimately was stemming from God’s decision to place his Holy Spirit on the Gentiles. Perhaps this helps explain why a voice repeated, “What God has cleansed, no longer consider unholy” three times to Peter in a vision (Acts 10:15-16). God had to prepare Peter for Cornelius’ invitation, because entering a Gentile’s home was an uncomfortable proposition for an observant Jew in the land of Israel.[21]

In our day a large number of Jews from the Lubavitch community have come to regard Rabbi Schneerson as the Messiah. Have these Messianic Jews been pushed outside of Judaism? Judaism is able to accommodate Messianism within its ranks, but the idea of God lavishing his Holy Spirit on men with uncircumcised sexual organs is more theologically challenging. For Paul, this stood at the heart of the mystery of the gospel, namely that the Gentiles (or sinners, as Jews called them) had been given an equal share in Israel’s redemptive heritage.

Writing Galatians 2:11-14, Paul described an incident where the new spiritual status of the Gentiles had generated some friction. Peter had lapsed into conduct that offended the non-Jewish believers. Hence, dealing with some practical ramifications of the mystery of the gospel, Paul found himself in Antioch charting a course between the conservative (and perhaps slightly ethnocentric) Jewish faction under James’s Jerusalem-based leadership on the one hand, and some insensitive (and perhaps ungrateful) Gentiles on the other.[22]

Is the mystery about which Paul preached and wrote new to us? Generations of Christians have been living with this mystery of the gospel for nearly two thousand years. Paul was explaining something new and marvelous for his generation. For us living today the mystery remains marvelous, but it is no longer new. Ironically, we feel very comfortable with the mystery of the gospel, perhaps so much so that we run the risk of taking our “engrafted” status for granted. Moreover, no longer is it the mystery of the gospel that we have difficulty understanding, but the other topics addressed in the New Testament that reflect traditional Jewish thinking. Because Christianity’s organic bond with ancient Judaism has eroded badly over the centuries, a number of concepts and topics that would have been clearly understood by first-century Jewish audiences and would not have required explanation have become difficult to comprehend. Jesus and Paul’s expectations for their first-century Jewish audiences were appropriate, but not for twentieth-century Christians who belong to a radically different age and culture.[23]

Returning to Paul’s letter, consider Galatians 2:9, where Paul recorded his brief description of the Jerusalem Council:

…and recognizing the grace that had been given to me, James, and Cephas and John, who were reputed to be pillars, gave to me and Barnabas the right hand of fellowship, that we might go to the Gentiles and they to the circumcised. They only asked us to remember the poor, the very thing I was eager to do.

Notice the little phrase, “the very thing I was eager to do.” As Paul traveled on his missionary journeys, he paid special attention to the needs of the poor. Paul did not limit himself to preaching and teaching. He also helped the poor.[24]

Shrinking the Camel

Each of the first three Evangelists recorded the story about a rich, young man who asked Jesus what was necessary to be a candidate for inheriting eternal life (Matthew 19:16-22; Mark 10:17-22; Luke 18:18-23). According to Matthew, the man asked, “What good thing must I do to have eternal life?” What verse of Scripture motivated that question? In Micah 6:8, the prophet said, “He has told you, O man, what is good and what the Lord requires of you…” Pastor Robert Lindsey suggested that the young man (who most likely posed his question in Hebrew) asked Jesus something close to “What good shall I do in order to inherit eternal life?”[25] The link to Micah 6:8 becomes more apparent once the question has been put into Hebrew. The key phrase is “mah tov” literally, “what good.” The rich young ruler had asked a sincere question. He sought to know what God required of him to inherit eternal life.

According to Luke, Jesus answered:

You know the commandments: Do not commit adultery, do not kill, do not steal, do not bear false witness, Honor your father and mother.

To this the young man replied, “All these I have observed from my youth.” This young man apparently felt that there was still something more. He was obeying the commandments—you shall not kill, commit adultery, steal, bear false witness, etc.

Now Jesus began to apply the pressure:

One thing you still lack. Sell all that you have and distribute to the poor, and you will have treasure in heaven; and come, follow me.

We are told that the young man departed saddened because he had much wealth.

About what did the young man originally come to ask Jesus? Eternal life. With what did Jesus end the discussion? He ended with an invitation to follow him or to become a member of his redemptive movement. Is the Kingdom of Heaven the same thing as eternal life? The NIV Study Bible suggests that the two are synonymous.[26] But, if a person spends time reading ancient rabbinic literature, he or she knows that eternal life and the Kingdom of Heaven are two different concepts. Eternal life is basically what we understand it to be, where a person goes after death. The Kingdom of Heaven, however, remains in full force now for those people who have made Jesus, Lord—not tomorrow, not when the Son of Man comes back to judge, but today. People who have said “yes” to Jesus belong to his redemptive movement, which he called the Kingdom of Heaven.[27]

In this story, the rich young man came to Jesus with a question about inheriting eternal life. Jesus basically answered, “You know the commandments—keep them.” Although the young man lived in accordance with the commandments, he wanted to experience a deeper level of spirituality and communion with God.[28] Yet, when faced with the cost of discipleship, which included freeing himself from the snare of materialism by laying up treasures in heaven, he hesitated to make Jesus Lord.[29]

Matthew, Mark and Luke each preserve a dialogue, which Jesus had with a lawyer.[30] According to Matthew, the lawyer came and asked Jesus, “What is the great commandment of the Torah?” And a similar discussion ensued.[31] In the end, Jesus complimented the lawyer by saying, “You have answered right; do this, and you will live,” [32] which includes an allusion to Leviticus 18:5.[33] I find it fascinating that Jesus did not deal with the lawyer in the same manner in which he dealt with the young man. Jesus did not offer the lawyer a personal invitation to become a disciple and thereby join God’s unprecedented redemptive movement over which Jesus presides. I suspect that Jesus viewed this conversation between him and the lawyer more in terms of a professional encounter. The lawyer seems to have been sparring with Jesus,[34] but not necessarily searching like the rich young man.

From the Rich Young Ruler story we learn that the phrase “treasure in heaven” functions as a sort of technical term for giving charity to the poor. Surely the concept drew inspiration from Proverbs 19:17. God has rated the poor as a wise investment. He acts as their guarantor. When we turn away from the poor, perhaps we underestimate God’s solvency or doubt his intention to repay his creditors.

The Rich Young Ruler story also indicates that Jesus’ followers or disciples pursue a lifestyle characterized by laying up treasure in heaven. The snare of materialism ranks among the more menacing threats for impeding obedience to God’s will. Jesus forcefully made this point when he said, “It is hard for a rich man to enter the Kingdom of Heaven! It is easier for a camel to go through the eye of a needle than for a rich man to enter the Kingdom of God” (Luke 18:25). Over the centuries, passing through the eye of a needle has not become an easier task for a camel, even if our preaching or lifestyles would suggest otherwise.

Yours and Mine

Luke recorded a story that Jesus told about a rich man and Lazarus. The story appears in Luke 16:19-31, and it reads as follows:

There was a rich man, who was clothed in purple and fine linen who feasted sumptuously every day. And at his gate lay a poor man named Lazarus, full of sores, who desired to be fed with what fell from the rich man’s table. Moreover, the dogs came and licked his sores. The poor man died and was carried by angels to Abraham’s bosom. The rich man also died and was buried; and in Hades, being in torment, he lifted up his eyes, and saw Abraham far off and Lazarus in his bosom. And he called out, “Father Abraham, have mercy upon me, and send Lazarus to dip the end of his finger in water and cool my tongue; for I am in anguish in this flame.” But Abraham said, “Son, remember that you in your lifetime received your good things, and Lazarus in like manner evil things; but now he is comforted here, and you are in anguish. And, besides all this, between us and you a great chasm has been fixed, in order that those who would pass from here to you may not be able, and none may cross from there to us.” And he said, “Then I beg you, father, send him to my father’s house, for I have five brothers, so that he may warn them, lest they also come into this place of torment.” But Abraham said, “They have Moses and the prophets; let them hear them.” And he said, “No, father Abraham; but if someone goes to them from the dead, they will repent.” He said to him, “If they do not hear Moses and the Prophets, neither will they be convinced if someone should rise from the dead.” (Luke 16:19-31)

This story illustrates a point that A. Marmorstein made: “Legends were more powerful allies of the theologians and teachers, apologists and preachers, than generally thought of.”[35] Teaching with legends and other story-line forms was an effective mode for communicating and influencing people’s thinking. In the synoptic gospels, Jesus did much teaching in the form of parables and stories. The challenge for modern readers is that Jesus presented theology in story form. Consequently, the responsibility rests upon us to coax the theological implications out of Jesus’ stories and parables.

The ancient sages of Israel sometimes spoke of humanity in terms of a threefold categorization: the saints, the average folk, and the wicked.[36] They observed that the wicked often accumulated wealth and had an easier lot in this world. In other words, good things such as wealth sometimes accrued to people who did not seem to merit them. Conversely, bad things sometimes happened to people who did not seem to deserve them. They also recognized that some people were born into miserable circumstances, while others enjoyed wealth and comfort. Accordingly, they concluded that a person’s lot in this life could be a mitigating factor, when he or she stands at the Great Judgement.[37]

How is the beggar Lazarus described when he was alive? He lived as a poor man who suffered from sores. He had a wretched lot in this life. That is all we hear about Lazarus. He lived mired in poverty and was chronically ill. The story does not comment on his piety—it merely says that he was poor.

Every day Lazarus sat outside the rich man’s gate and slowly wasted away because nobody clothed, fed or nursed him back to health. Lazarus owned nothing, whereas the rich man possessed much, but he made little or no effort to relieve Lazarus’ suffering. Perhaps he assumed that Lazarus deserved his lot because of some undisclosed sin or a simple lack of industriousness. Whatever his reasoning, the rich man certainly had multiple compelling justifications for neglecting Lazarus.

Sometime in the second century A.D. the rabbis formulated a saying that may hold relevance for a discussion about the story of Lazarus and the rich man:

There are four types among people: The one who says, “What is mine is mine, and what is yours is yours.” This is the average person. The one who says, “What is mine is yours, and what is yours is mine.” This is the simpleton. The one who says, “What is mine is yours, and what is yours is yours.” This is the saintly person. The one who says, “What is mine is mine, and what is yours is mine.” This is the wicked person.[38]

Why did some rabbis claim that the person who says, “What is mine is mine, and what is yours is yours” resembles a person from Sodom? The prophet Ezekiel once said something about the people of Sodom that is often overlooked in Christian preaching and teaching. They were proud, had plenty of food, were at ease, but the hand of the poor and the lowly they did not strengthen (Ezekiel 16:49). Therefore, according to Ezekiel, this was the sin of Sodom. Although the cardinal sin of the men of Sodom in Genesis 19 was lewd misconduct, in ancient Jewish interpretation, Sodom’s sin became linked to pride and contentment, which resulted in neglect of the poor.[39]

Ezekiel addressed an issue similar in nature to one raised by the story of The Rich Man and Lazarus. The rich man saw Lazarus sitting outside his gate but did not do anything to relieve his suffering. He may have reasoned, “What is mine is mine, and what is Lazarus’ is Lazarus’.” In Jesus’ day that attitude would have been booked as a spiritual felony. The rabbis emphasized this point by suggesting that even an average person, who thinks what is his is his, runs the risk of being like a Sodomite.

Conclusion

In this study I have tried to bring into focus one area that pious Jews in Jesus’ day stressed for proper conduct. Sometimes their emphases differed from the ones we see in the text. In Ezekiel, we read a verse about Sodom, which identifies the sin of Sodom as a failure to strengthen the hand of the poor. Jesus told a story about a rich man who was finely clothed and ate sumptuously. He was at ease, while poor Lazarus was at his gate.

This simple story highlights a major theme in Jesus’ theology: reaching out to the poor and downtrodden. Ancient Jews referred to such activity as laying up treasures in heaven. This concept constitutes a foundational component in the overall message of the Kingdom of Heaven.

Laying up treasures in heaven pertains to helping the poor as Sirach 29:9-13, Tobit 4:7-11, and Matthew 19:21, Mark 10:21, and Luke 18:22 indicate. To this collection of passages we may also add Luke 14:12-15: “…when you give a reception, invite the poor, the crippled, the lame, the blind, and you will be blessed, since they do not have the means to repay you; for you will be paid at the resurrection of the righteous.”[40]

Realizing that laying up treasures in heaven functions as a sort of technical term for helping the poor in Jewish tradition challenges Christians in affluent western countries in a significant way. We regularly drop money into the collection baskets during the morning offertory each Sunday. But for what purposes is this money used? Although maintaining the church building, keeping the property landscaped, and paying the utilities are worthy endeavors, only gifts of time and money that relieve the suffering of the needy is credited to our heavenly bank accounts. At least this is what Jesus and other Jewish sages taught. As David Bivin once preached from the pulpit of the Narkis Street Congregation in Jerusalem, “We may be surprised to one day learn that we have little balance in our heavenly bank account, because we were not helping the poor. Jesus said, ‘Lay up treasure in heaven.’ In Hebrew, this heavenly treasure is called tsedakah, or, in English, alms or charity.”[41]

From studying the Bible, I have come to see two places where, as a general principle, God dwells with people. One is with the community of faith. God’s redemptive power flows through people who have made Jesus Lord. Jesus stands at the head of a redemptive movement, and those who are part of it are described as poor in spirit.

The Divine Presence is attracted to people who are poor in spirit. They are spiritually dependent upon God, contrite in spirit, and readily yield to his desires. This reminds us of the beatitude: “Blessed are the poor in spirit, for these type of people constitute the Kingdom of Heaven.” (In English translations of Matthew 5:3, the genitive Greek pronoun αὐτῶν (auton) is treated as a possessive, yet auton would be better translated as a partitive genitive, i.e. “from these” instead of “belonging to these.”)[42]

The other place where God remains active is among the brokenhearted (cf. Isaiah 57:15). Based upon what Scripture says, God dwells with the crushed, the brokenhearted, and the downtrodden. People whose dignity has been crushed, whose physical bodies are failing, whose hopes and aspirations have been shattered, whose lives are mired in poverty attract the Divine Presence. Acute and chronic suffering tends to purge a person of pride and self-reliance and to produce in him or her a genuine longing for a touch from God. For that reason Jesus provoked his audiences by suggesting that tax collectors and harlots would enter the Kingdom of Heaven before others.

Laying up treasures in heaven resembles the classical message of the prophets—feed the hungry, clothe the naked and visit those who are sick and imprisoned—but approached from the perspective of God’s faithfulness in rewarding those who do these kind acts. Laying up treasures in heaven for a follower of Jesus is like higher education for a university professor. It is already an integral part of that person’s life. To make Jesus Lord and to become a participant in the Kingdom of Heaven is to dare to go beyond the classical message of the Prophets. It means being on call 24 hours a day, 365 days a year with our God-given talents, skills, and resources in hand as a partner with God in spreading hope, healing and redemption in a hurting world.

- [1] Lamentations Rabbah, Proem 31. For an English translation, see Lamentations in Midrash Rabbah (trans. A. Cohen; 3rd ed.; London: Soncino, 1983), 57. ↩

- [2] M. Taanit 2:1. For an English translation, see The Mishnah (trans. Herbert Danby; Oxford: Oxford University, 1933), 195. ↩

- [3] For further discussion about Luke’s use of “stichwords,” see Joseph Frankovic, Reading the Book (Tulsa, OK: HaKesher, 1997), 37-38 and David Flusser, Judaism and the Origins of Christianity (Jerusalem: Magnus Press, 1988), 152. ↩

- [4] The precise meaning of the Greek adjective haplous in Matthew 6:22 remains elusive. It may mean “clear, healthy, sound, simple, single, or sincere.” Note that haplous is antithetically paired with the Greek adjective ponaeros, which means “evil, bad, wicked, sick, in poor condition” (see Walter Bauer, A Greek-English Lexicon of the New Testament and Other Early Christian Literature [5th rev. ed., 1958; Chicago: University of Chicago, 1979], 86, 690-91). In light of the context and the pairing of ophthalmos…haplous with “bad eye,” I am inclined to say that the Hebrew idioms “good eye” and “bad eye” inspired the Greek phrases “ophthalmos…haplous” and “ophthalmos…ponaeros.” The idiom “good eye” appears in Proverbs 22:9: “A good eye will be blessed, because it has given of its bread to the poor.” Even today in Israel, collectors of charity say, “Give with a good eye.” Note, too, that in Romans 12:8, the noun haplotaes, which is related to haplous, means “generosity.” The idiom “bad eye” appears in m. Avot 5:13. ↩

- [5] David Flusser has pointed out that Luke joined this saying about serving God and Mammon to the parable because the word “mammon” was common to both (cf. Luke 16:13 and 19) (see Flusser, Judaism and the Origins of Christianity, 152). ↩

- [6] Editions of the Bible prepared by the Catholic and Eastern Orthodox Churches include the Wisdom of Ben Sirach. In the wake of the Reformation, abandoning the cannon of the early church (namely the Septuagint) and following the lead of the rabbinic canon, Protestants elected not to include the Apocrypha as part of their Bible. ↩

- [7] In antiquity, people often hid their valuables in the ground. They viewed this practice as being responsible and prudent, similar to the way people today view storing valuables in a safety deposit box. This sort of thinking is clearly reflected in a variety of ancient sources. From Roman literature, one may cite the behavior of the miser in Aesop’s fable entitled “The Miser.” In Matthew 25:25, one of Jesus’ parabolic characters explains to his demanding master, “So I was afraid, and I went and hid your talent in the ground.” Writing about the First Jewish Revolt against Rome, Josephus described how Roman soldiers tortured Jewish prisoners in order to learn the location of their buried treasures (Jewish Wars 7:112-114). Lastly, one may call attention to the famous maxim of St Basil, “…and the gold that you have hidden in the ground belongs to the poor.” ↩

- [8] Sirah 29:9-13. The Oxford Annotated Apocrypha (ed. Bruce Metzger; expanded ed.; New York: Oxford University, 1977), 166. ↩

- [9] The development in meaning of the word tsedakah from the biblical to mishnaic period, already finds expression in Daniel 4:24(27), where the Aramaic cognate tsidkah is in parallel with “showing mercy to the poor” (Everyman’s Talmud, 219). For further discussion, see Joseph Frankovic, The Kingdom of Heaven (Tulsa, OK: HaKesher, 1998), 3-8. ↩

- [10] Everyman’s Talmud, 221. Also is the verse on Tsedakah Box. ↩

- [11] Note that Ben Sirach claimed that almsgiving protected more effectively than a mighty shield. The Hebrew word tsedakah was often rendered in Greek as dikaiosunae, even when it carried the meaning of almsgiving. Compare Matthew 6:1. Keeping this in mind, one wonders whether the breastplate of righteousness mentioned in Ephesians 6:14 should be understood in similar terms. ↩

- [12] Overall, the Old and New Testaments have little to say on marriage. Nevertheless, Jewish thinking on the subject was highly developed. As part of Jewish tradition and the Oral Law, Jewish views on marriage and family life have had a limited influence on Christian preaching and teaching. Although the New Testament does not preserve much information about Jesus’ and Paul’s views regarding marriage and the family, I am sure that both were well versed on what Jewish tradition prescribed. I am always amazed to enter a bookstore that caters to Evangelical/Charismatic Christians and see the numerous books that Christian authors have written on marriage. Few of these authors have made any serious attempt to consult Jewish sources on marriage. Yet Jesus and the apostles after him viewed marriage through the lenses of their Jewish religious heritage. Some of that heritage flowed into rabbinic Judaism and today remains preserved in the literature that the rabbis wrote. ↩

- [13] B. Gittin 7b (top). ↩

- [14] The entire passage comes from Tobit 4:7-11 (The Oxford Annotated Apocrypha, 66). ↩

- [15] Tobit 4:10 differs from Proverbs 10:2 in syntax, the tense of the verb, and eleaemosunae appears in place of dikaiosunae.Unlike dikaiosunae, which carries several meanings, eleaemosunae only means “kind deed” or “charitable giving.” See Walter Bauer, William Arndt, and Wilbur Gingrich, A Greek-English Lexicon of the New Testament and Other Early Christian Literature (2nd rev. and augmented ed.; Chicago: University of Chicago, 1979), 249. ↩

- [16] Note that eleaemosunae is underneath the English “charity” in Tobit 4:10 and “almsgiving” in Tobit 12:9 (The Oxford Annotated Apocrypha, 66, 73). See also A. Cohen, Everyman’s Talmud (New York: Schocken Books. 1975), 221. ↩

- [17] For the rabbinic version, see t. Peah 4:18. See also Josephus, Jewish Antiquities 20:17-96. ↩

- [18] Josephus, Jewish Antiquities 20:4, 92-96. ↩

- [19] See Romans 11:25-26, Colossians 1:27 and Ephesians 3:3-6. ↩

- [20] See Acts 19:8, 20:25 and 28:31. ↩

- [21] Note the effort that the centurion made to prevent Jesus from having to deal with a similar awkward situation (Luke 7:6-8). ↩

- [22] Regarding the awkward circumstances for social contact between Jews and Gentiles in the first century, see the insightful remarks in Robert Lindsey, Jesus, Lord of Capernaum (Tulsa, OK: HaKesher, 1998), 10-12, 20-21. A brief, helpful discussion of the confrontation between Paul and Peter in Antioch may be found in Wayne Meeks and Robert Wilken, Jews and Christians in Antioch in the First Four Centuries of the Common Era (Missoula, Montana: Scholars Press, 1978), 1-2, 13-20. ↩

- [23] We must work at developing sensitivity to the text that enables us to identify the major concerns of first-century Jews. They appear throughout the synoptic gospels and epistles, but too often escape the attention of twentieth-century English readers. When there is widespread recognition of this challenge in the church, those sitting in the pews will initiate changes that will bring about a sweeping reform in the way we educate those who stand in our pulpits. For further discussion, see Frankovic, Reading the Book, 47-52. ↩

- [24] In 2 Corinthians 9:6-9, Paul wrote some advice about giving.

Now this I say, he who sows sparingly shall also reap sparingly. And he who sows bountifully, shall also reap bountifully. Let each one do just as he has purposed in his heart, not grudgingly or under compulsion; for God loves a cheerful giver. And, God is able to make all grace abound unto you, that always having all sufficiency in everything, you may have an abundance for every good deed.

Now follows his proof text from Psalms 112:9: “As it is written, ‘He scattered abroad, he gave to the poor, his righteousness abides forever.’” How did Paul understand the Hebrew word, tsidkato, from Psalms 112:9? It is translated as dikaiosunae autou in the Greek of 2 Corinthians 9:9. How could we translate his righteousness in 2 Corinthians 9:9 more dynamically? Could we say that God’s charitable deeds endure forever? First-century Jews saw a connection between God giving to the poor and his charity (righteousness) abiding forever. They interpreted Psalms 112:9 to mean that God’s redemptive activity endures forever. (Or, if one prefers, in a more narrow sense, his charitable activity endures forever.) God is always reaching out to the poor, to the broken, to the crushed; therefore, his righteousness abides forever! Paul apparently understood Psalms 112:9, which he quoted in 2 Corinthians 9:9, in the same manner the author of Tobit understood Proverbs 10:2. For both writers, tsedakah meant something like charity or almsgiving. ↩

- [25] See Robert Lindsey, A Hebrew Translation of the Gospel of Mark (2nd ed.; Jerusalem: Dugith, 1973), 127, and David Bivin, “Jerusalem Synoptic Commentary Preview: The Rich Young Ruler Story,” Jerusalem Perspective 38 and 39 (May-Aug. 1993): 15. ↩

- [26] The NIV Study Bible offers this comment on Matthew 19:16: “eternal life. The first use of this term in Matthew’s Gospel (see v. 29; 25:46). In John it occurs much more frequently, often taking the place of the term ‘kingdom of God (or heaven)’ used in the Synoptics, which treat the following three expressions as synonymous: (1) eternal life…, (2) entering the kingdom of heaven…and (3) being saved” (The NIV Study Bible [ed. Kenneth Barker; Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1985], 1469, 1470. ↩

- [27] See Joseph Frankovic, The Kingdom of Heaven (Tulsa, OK: HaKesher, 1998), 7, and Brad Young, The Jewish Background to the Lord’s Prayer (Austin: Center for Judaic-Christian Studies, 1984), 10-17. ↩

- [28] Matthew has underscored this element of the story. In his gospel the young man asked, “What do I still lack?” ↩

- [29] Regarding the cost of discipleship, see Luke 14:26-32. ↩

- [30] See Matthew 22:35-40, Mark 12:28-34, and Luke 10:25-28. ↩

- [31] Apparently, Luke was reminded of the Rich Young Ruler story when he wrote about this lawyer. He introduced this story as being about inheriting eternal life. Luke may have realized that Jesus’ allusion to Leviticus 18:5 in verse 28 pertained to eternal life. ↩

- [32] See Luke 10:28. ↩

- [33] In Jewish tradition, Leviticus 18:5 was understood to be a reference to eternal life. See Rashi on Leviticus 18:5. See also the references listed for τοῦτο…ζήσῃ in The Greek New Testament (eds. K. Aland, M. Black, C. Martini, B. Metzger, and A. Wikgren; 3rd corrected ed.; West Germany: United Bible Societies, 1983), 253. ↩

- [34] See Joseph Frankovic, “Is the Sage Worth His Salt?” Jerusalem Perspective 45 (July/August 1994): 12, 13. ↩

- [35] A. Marmorstein, “The Unity of God in Rabbinic Literature,” Hebrew Union College Annual (1924): 469. ↩

- [36] See Sifre Zuta, p. 27 and Rosh HaShanah, 16b. ↩

- [37] See Sifre Zuta, p. 27 and Rosh HaShanah, 16b. ↩

- [38] M. Avot 5:10. For an alternative English translation, see Danby, 457. Jesus probably knew this saying from Avot in an earlier, simpler form. In the parable of the day laborers in the vineyard and their wages (Matthew 20:1-15), Jesus depicted the landowner, who represents God, as if he is the saint, and the day laborers as if they were average men (or perhaps Sodomites). Note Matthew 20:14-15. See Brad H. Young, Jesus the Jewish Theologian (Peabody, MA: Hendrickson, 1995), 136-37. ↩

- [39] See also “Emulating the Ways of Sodom,” Jerusalem Perspective 55 (Apr.-Jun. 1999): 38. ↩

- [40] Years ago, Father Richard Thomas and others working with him at Our Lady’s Youth Center in El Paso, Texas did just what this passage said. They hosted a Christmas meal at a city dump in Juarez, Mexico. What happened that day revolutionized the ministry that Father Thomas continues to oversee in the Juarez and El Paso area. ↩

- [41] David Bivin, “Doers of the Word” in Sermons from Narkis (Jerusalem: Jerusalem Perspective, 1996), 15. ↩

- [42] See Brad H. Young, Jesus and His Jewish Parables (Mahwah, NJ: Paulist, 1989), 230-35. ↩